Correction appended

"Better a dinner of herbs …" Proverbs 15:17

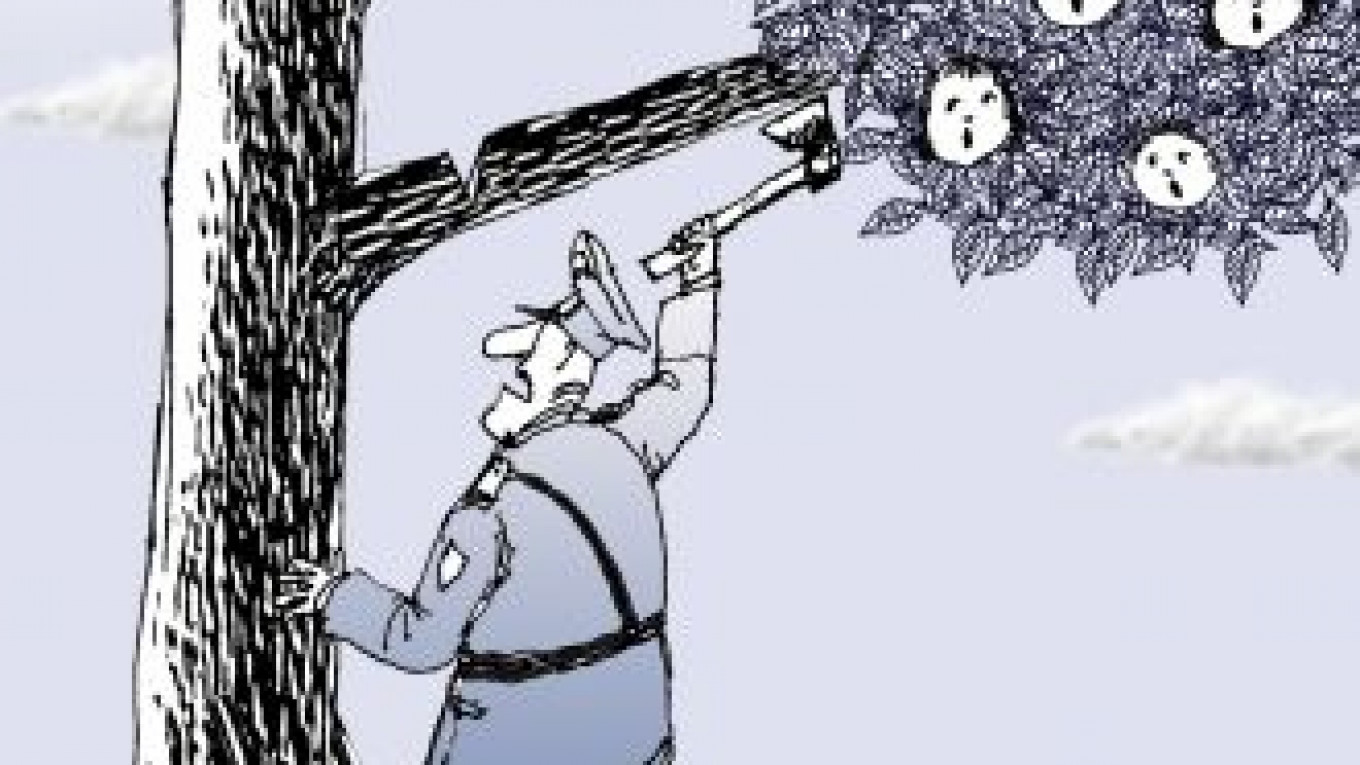

These days, nothing unites Russians more than their opposition to a federal bill on family and social services. Rallying under the slogan "Hands off our children," people are staging protests, signing petitions and going online to threaten an even bigger public outcry.

Why do government attempts to interfere in family life cause such hostility among most Russians? Because they are convinced that the state's child-care policies will not support families but instead cause their destruction and lead to the humiliation of children.

If children's wishes are ignored, it means the powers-that-be are up to no good.

Speaking about 9-year-old Dasha Popova, who was kidnapped in Rostov-on-Don and held for ransom for more than a week, senior child psychologist Anna Portnova in Moskovsky Komsomolets: "She needs psychological counseling to cope with stress. Otherwise, she may suffer from depression, alcoholism and personality disorders in the future."

The girl was returned to her family alive and unharmed on Sept. 27, but Portnova said urgent "treatment to avert the chronic stress that usually affects hostages and threatens significant repercussions" was required.

Admittedly, the girl was kidnapped by criminals, not social workers. Yet what is the difference between kidnapping and the forcible removal of a child from a home and into state custody? Children can be seized right now by social workers for, say, their parents' debts for municipal services. "Pay your bills, and we'll return your children," social workers Vera Kamkina in St. Petersburg when they took away all four of her children in 2010. Unfortunately, there are quite a few similar cases. But what does a child know or care about debts?

A child can become an innocent hostage to fortune, sometimes removed by the police and with brute force. The child is a prisoner who cannot escape. Cries and pleas fall on deaf ears.

If this treatment can inflict such psychological damage after one week, what will be the outcome of a longer period? What happens to Russian children who are forcibly wrested from their parents?

Kristina Serganova, 15, was taken from her mother together with her younger sisters in the Arkhangelsk region. Why? The family was considered "socially inadequate," or, to put it bluntly, too poor. Kristina preferred poverty with her mother to state care. She escaped from the children's home several times but was recaptured and returned. Finally, in January.

Those so mindful of her well-being can congratulate themselves.

Still, there have been successful escapes. A 12-year-old Russian girl was taken into state care directly from her school in Finland but in April. Her parents immediately loaded their five children into a car and fled to Russia, sacrificing everything — but saving their kids.

Yet some children are too young to escape or express their wishes. What about them? Professor Heinz Wirst, one of 50,000 Russian children taken from their parents and transported to the Third Reich by the SS, once said: "A child feels what is happening, even subconsciously. I shall search for my parents' graves as long as I live."

Sasha Leto, a fair, blue-eyed 2-year-old, was adopted by a German family who treated him as their own. But back in his Crimean home village, the old folks recall how the weeping toddler was dragged away by the SS. Wirst, learning of his roots many years later, changed his name to Alexander Leto.

Even now, former inmates of the Nazi's Lebensborn program seek their true relatives. They were seized from their "unsuitable" Russian parents way back then, to be given an upbringing considered fit and proper by the Third Reich.

Children's rights ombudsman Pavel Astakhov says 60,000 children are removed annually from their parents, all in the interests of their well-being. I would venture to say that what Russian children and their parents think of such solicitude is painfully obvious.

Correction: Due to an editing error, two names were misspelled in an earlier version of this article. The correct name is Sasha Leto, not Sasha Lito, and the Nazi program was Lebensborn, not Lebersborn.

Irina Ratushinskaya is a poet and writer.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.