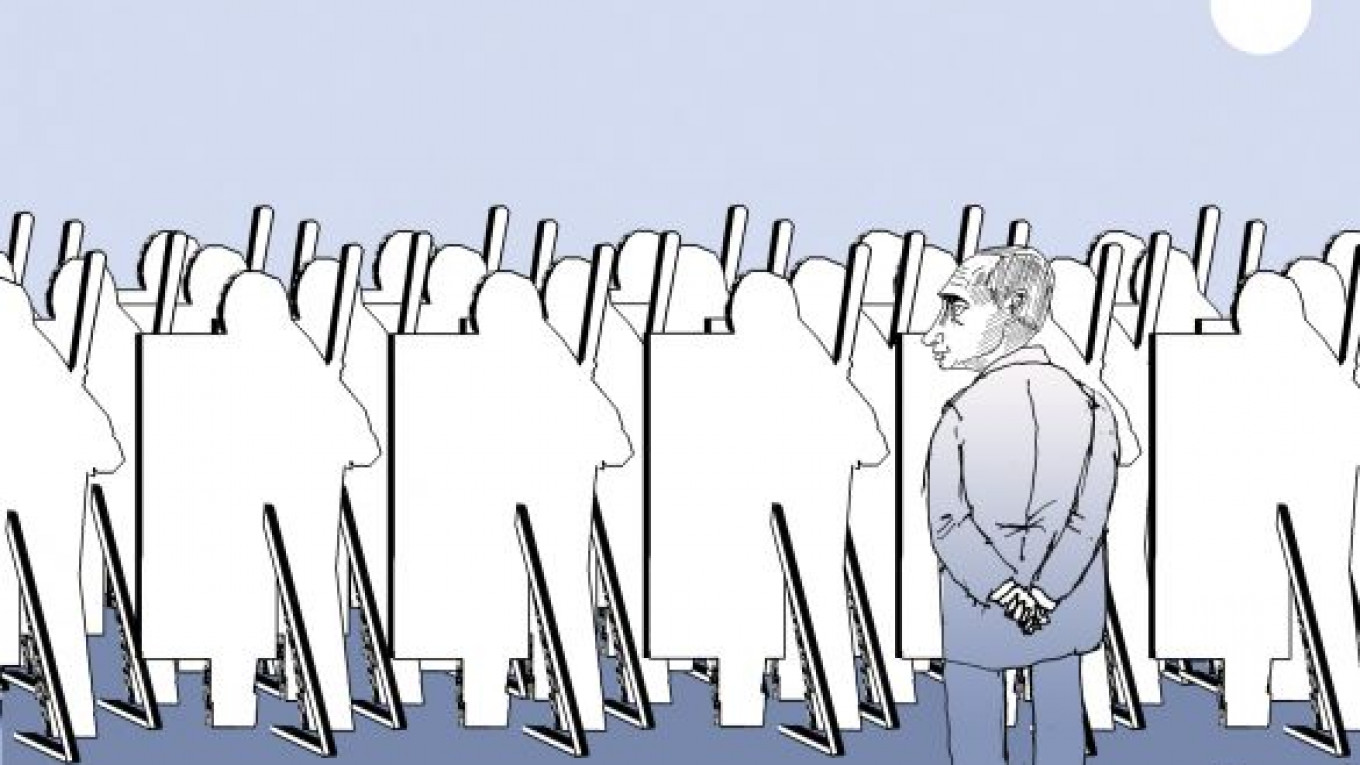

All hopes seem to have faded that President Vladimir Putin would emerge after re-election as some upgraded "Putin 2.0" – that is, an instigator of much needed structural and political reforms. The legal foundation for mass political repression was laid by a flurry of legislation rushed through the State Duma last week. The laws suppress free speech by giving the government power to close down blacklisted websites; make libel and slander of government officials a felony, punishable by fines of up to 5 million rubles ($165,000); brand dissident nongovernmental organizations that receive any foreign funding as "foreign agents"; and sharply increase the punishment for taking part in unauthorized protest rallies.

Putin and his cohorts in the Duma seem to see themselves as being besieged by enemies from all directions: in Syria, Central Asia and the Caucasus, while paid foreign agents try to occupy the streets and squares of Moscow. Putin brushed aside criticism of the NGO foreign agents legislation by publicly reiterating his long-held opinion that those who take foreign money dance to a foreign tune. Leading opposition figures have been harassed recently, their homes have been searched, and the number of jailed dissidents has been growing. The stage seems to be set for a showdown.

During the past several years, the Putin regime has effectively dispersed protests by relatively small numbers of activists who gathered in Moscow or St. Petersburg on the 31st day of a given month to support the Constitution's Article 31, which asserts the freedom of peaceful assembly. But the regime has been fumbling in its reaction to the massive protests that began in Moscow in December after the fraudulent Duma elections. Some rallies and marches have been allowed to proceed peacefully, while in other cases OMON riot police have used random violence and arrested dozens of protesters. The protest movement, combining nationalists, leftists and pro-Western liberals, has not dissipated since Putin scored his expected landslide re-election in March. In the fall, the social base of the protest movement may increase together with inflation as Muscovites return from their dachas and the long-awaited summer recess.

The Kremlin hopes to marginalize and downsize the protest movement by scaring the middle-class participants with hefty fines for minor offenses, libel or slander that may lead to confiscation of assets and property or restrictions on foreign travel. If the efforts fail, Putin and his cohorts may be in deep trouble, since the legitimacy of the authoritarian regime – like any autocracy — is not based on election results but on total control of the streets of the capital and the effective suppression of public opposition.

Moscow today has an official population of about 12 million, but there are millions of migrants from other Russian provinces and from republics of the former Soviet Union living unofficially or on temporary permits in Moscow and in the outlying suburbs. Estimates by City Hall put the workday population of Moscow at some 20 million. If 5 to 10 percent of the Moscow population becomes actively restive and up to half the population supports the agitators passively, the task of controlling all the streets and effectively imposing a curfew is an uphill job.

Recent polls indicate that the level of discontent is reaching those proportions. The regime would need more than 100,000 well-trained and motivated riot police to control Moscow streets and neighborhoods around the clock. The successful suppression of the "green" protest movement against massive election fraud in Iran in 2009-10 was greatly facilitated by thousands of Basij, well-organized and ideologically motivated paramilitary militia backing up the relentless use of force by the official police. Putin does not have any Basij equivalent, while his riot police are limited in number. Moscow has only 2,000 specialized OMON riot police and another 2,000 in the 2nd Moscow police regiment. To supplement this inadequate number, thousands of OMON police officers were moved to Moscow from other provinces during recent mass protests. But the overall number of OMON police in Russia is less than 30,000, and not all can be moved to Moscow or permanently deployed in the city, especially if scattered protests engulf St. Petersburg or some other large cities.

Moreover, the Putin regime has failed to build a professional military. The Defense and Interior ministry troops consist of badly trained and poorly motivated conscripts who serve only one year, and they are led by disgruntled officers. During recent protests in Moscow, the skinny 18-year old conscripts of the Dzerzhinsky Interior Ministry division were deployed in riot gear but were never actively used to assault the crowds with batons. There are some 50,000 other police officers serving in Moscow, but these are traffic and precinct cops dominated by corrupt officers with low moral sensibility and dubious riot training.

In reserve to back up the OMON in Moscow, there are armored police vehicles with water cannons and tear-gas grenade launchers mounted on trucks, so crowds of protesters may be dispersed and chased from street to street. But after major clashes on May 6, the relatively small OMON force from the provinces seemed to get lost in the maze of downtown Moscow as self-organized groups of protesters dispersed and regrouped from one street or square to another, day after day.

Putin will not meet the unrest with adequate reforms, while the repressive alternative is lacking in strength or credibility. As soon as the moral and physical fortitude of the overstretched OMON begins to crumble, control of Moscow may be lost. Since Russia is overcentralized, the loss of Moscow inevitably means the loss of the entire country. In Russia, just like in France, revolutions are decided in the capital only, while the provinces gaze on in bewilderment.

Pavel Felgenhauer is a columnist with Novaya Gazeta.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.