KASIMOV, Ryazan Region — Saturday is wedding day in Kasimov, a crumbling provincial town 250 kilometers from Moscow. Precessions of honking cars make their way down Sovetskaya Ulitsa, past waving pedestrians. The few restaurants are booked for wedding banquets.

It's an unlikely time to talk politics, and yet that is what several dozen outsiders have driven several hours to do.

Ever since disputed State Duma elections sparked an opposition revival beginning in December, activists have been paying more attention to Kasimov and other provincial towns where discontent is high and salaries are low.

Heeding a call by opposition leader Alexei Navalny on his blog, about 55 activists from Ryazan and Moscow drove to Kasimov to urge its 33,000 residents to vote in upcoming city legislature elections. Suspicions are high that the elections are being used to place a high-ranking United Russia official in the Federation Council.

The official, Andrei Chesnakov, has not commented on the rumors, and former city legislature Speaker Yevgeny Gerasimov said a May decision to dissolve the body was meant to "reflect new political realities," according to RZN.info, a local news site. Gerasimov said the inauguration of President Vladimir Putin and election reforms to simplify the registration of political parties had compelled the legislature to "change with the times."

But activists hope to expose what they call a dirty trick and at the same time dislodge United Russia from its dominant role in the legislature, sending a signal that the powerful ruling party can be beat in free and fair elections.

Nominees for the Federation Council must be elected officials, a requirement that inspired a snap-election in St. Petersburg in August 2011. That election saw former Governor Valentina Matvienko elected to two district councils with more than 90 percent of the vote, according to official results. Later that month, she was appointed to the Federation Council, where she currently serves as speaker.

Chesnakov, No. 2 on United Russia's ticket in the July 22 elections in Kasimov, a town to which he had no prior links, is a virtual shoo-in for a vacant Federation Council seat.

"United Russia has done so many things wrong. If I had hair on my head, it would stand up and never come down," Sergei Kochetkov, 47, an opposition activist from Moscow, told a resident as he and the others went door-to-door, distributing fliers reminding locals to vote.

They also handed out anti-United Russia fliers, including one designed to look like a leaflet from the ruling party and linking utility prices to support for the party.

"If turnout is less than 25 percent, they can scare and steal their way into a majority," Kochetkov told a blind man sitting on a stoop beside a sleeping cat. "Observers from Moscow will make sure the vote isn't rigged."

The locals greeted activist Kochetkov with a smile and often an anti-government rant. None said they were voting for United Russia, and only one said he was voting for the Liberal Democratic Party.

Police were ever-present in the city center, which was otherwise filled with wedding party after wedding party. "Saturday is wedding day," a local woman said, explaining why there was nowhere to eat in the city's rundown center.

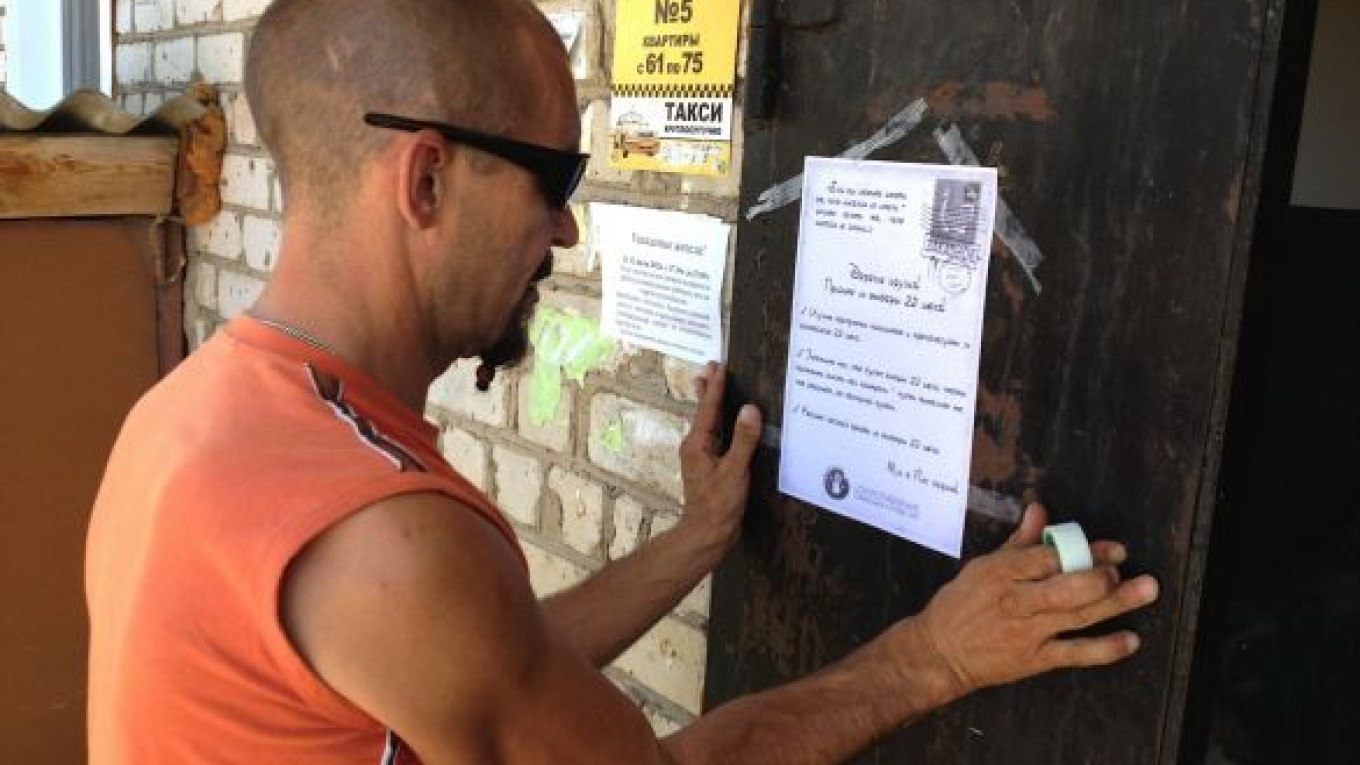

Fliers spotted on and around crumbling apartment blocks showed that agitators from the Liberal Democratic Party and Yabloko had also been making the rounds, but aside from a bored teenage girl taking cover from the sun in a blue LDPR tent, none of them were encountered.

One group of opposition activists said they ran into pro-Kremlin youths handing out a flier that compared opposition leaders to performers in a circus led by "artistic director" U.S. Ambassador Michael McFaul.

Three opposition activists were briefly detained for "illegally" pasting fliers to buildings, a charge that carries a fine of up to 1,000 rubles.

Activist Nikolai Levshchits, who helped organize the day under the aegis of Navalny's "Good Truth Machine," said it was a miracle that Saturday's 4-hour trip from Moscow took place at all, given that opposition attention and resources are tied up on Krymsk flood relief.

"It could have been better organized," he said. "Activists could have been better trained in what to say. But it's quite obvious that these trips can be very effective."

The trip could also serve as a dry-run for a gubernatorial election scheduled in the Ryazan region in October.

United Russia won 49 percent of the votes in the Kasimov region in the Duma elections in December, a figure that is similar to its nationwide haul.

But conversations with more than a dozen locals revealed seething anger toward the ruling party that appeared to be much more widespread than the election results would suggest. The grievances were many — corruption, education, health care, pensions, jobs — as was a sense that ordinary people were powerless to address them, including through elections.

Svetlana, a 72-year-old pensioner, said her 6,000 rubles ($185) per month pension wasn't enough to support herself and four young grandchildren after her son was injured in an accident.

Nevertheless, she said she wasn't sure she would vote because, like many locals, she believes all politicians are crooks and thieves.

"There are black dogs, and there are brown dogs. But they all have the same doggy soul," she said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.