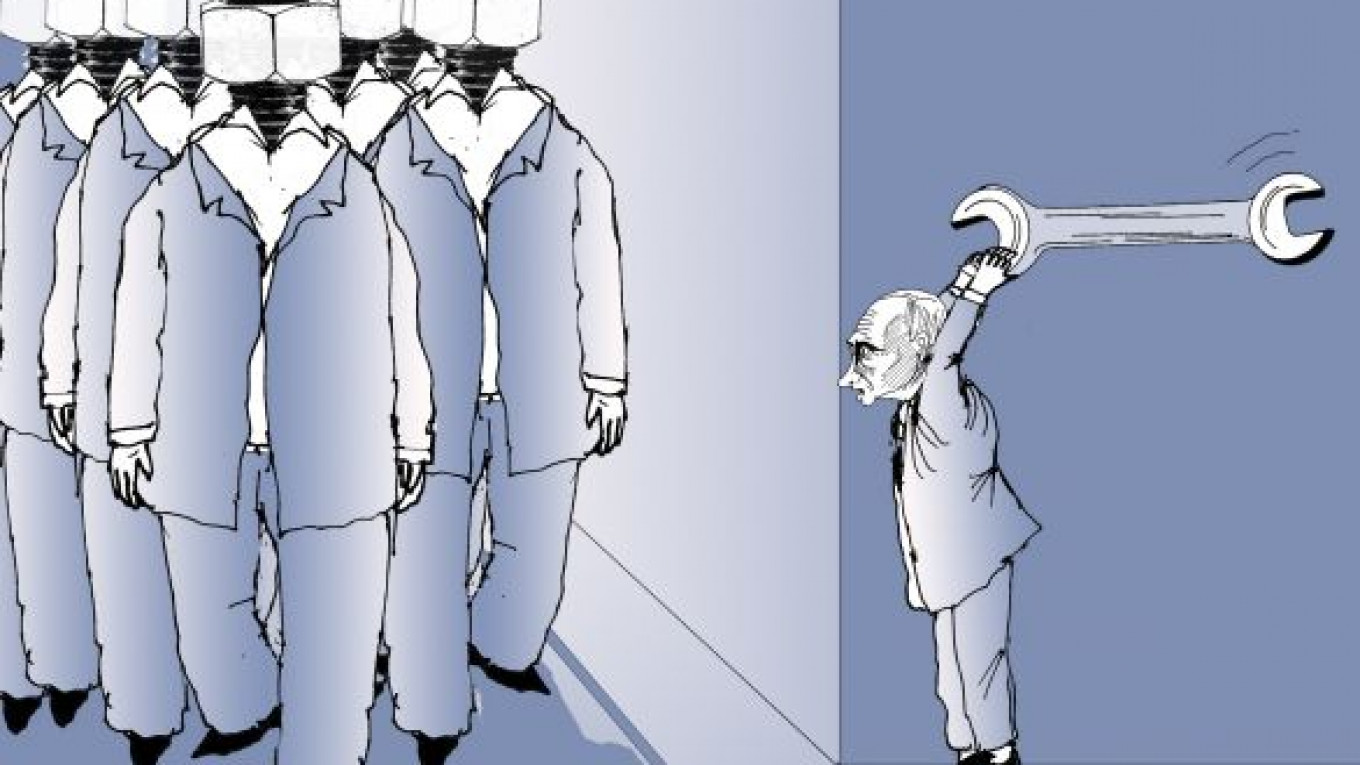

On March 7, three days after Vladimir Putin was elected president for the third time, he answered a question from a journalist about wide speculation that he would now have a free hand to tighten the screws on the people. He said only half-jokingly: “Of course we will. How can we manage without it? Don’t let your guard down.”

Although he has not kept his word on most of his other promises, he is definitely fulfilling this one. The latest crackdown began in May when authorities detained a number of activists and introduced stiffer fines and jail sentences for violating the rules governing mass rallies. Last week, the State Duma introduced a bill that would criminalize defamation, making it punishable by a fine of 500,000 rubles ($15,200) or up to five years in prison. The government was also given free reign to shut down undesirable Internet sites and brand nongovernmental organizations that receive foreign funding with the humiliating status of “foreign agents.”

What is behind this deluge of repressive legislation over the past month, and what are their implications?

U.S. political scientist Adam Przeworski once wrote that “authoritarian equilibrium rests mainly on lies, fear or economic prosperity.” Russia is no exception. Its authoritarian regime has relied on all three elements to varying degrees. Rapid economic growth from 2000 to 2007 allowed officials to buy voter loyalty, powerful state propaganda was largely able to create the illusion that Putin was building a “great Russia,” and the widespread fear of political change helped the Kremlin preserve the status quo.

But the wave of protests from December to June showed that the old model of authoritarian rule no longer works. It has become increasingly difficult for the government to buy voter loyalty, especially as incomes have fallen and the demand for good governance has risen. Government propaganda has become less effective as confidence in the country’s leaders wanes and discontent with the current regime continues to climb. Moreover, the mass rallies have shown that Russians are shedding their fear of challenging the Putin regime.

But the authorities are not willing to rely on mass repression as a survival tactic. By no means is this driven by moral constraints. After all, Putin had no qualms about killing hundreds of hostages along with the terrorists during the attacks on the Dubrovka theater in 2002 and the Beslan school in 2004.

The real problem is that Putin can’t rely on the siloviki as an effective weapon to repress the people on a mass scale. This would run the high risk of violent resistance. What’s more, the siloviki could easily turn on Putin and his supporters if they feel that the popular tide is turning against the Putin regime. That is why Putin is resorting to his customary tactic of provocation and intimidation. The fear experienced by Putin and his inner circle is forcing them to conduct a policy of fear.

The authorities have deliberately written legislation with vague wording so they can punish any undesirable individual or organization. At the same time, however, one of the investigators leading the blatantly trumped-up case against protesters at the May 6 rally at Bolotnaya Ploshchad openly told a lawyer that the 13 defendants were deliberately chosen from various social groups to show all active and potential protesters that nobody is safe from persecution.

The same goal motivated the State Duma to partially strip immunity from Communist Party Deputy Vladimir Bessonov, who is far from the Kremlin’s most strident critic. But he was made an example for the more vocal opposition deputies, such as A Just Russia Deputies Gennady Gudkov and Ilya Ponomaryov, who may be punished as well if the protest movement heats up.

Thus, current efforts to tighten the screws are aimed less at throwing every dissident in jail and more at intimidating potential supporters from joining the opposition protest movement. In this way, the Kremlin is trying to frighten the Russian people into submission and apathy.

Future developments will depend on how Russian society responds to the Kremlin’s “politics of fear.” This strategy will clearly fail if Russians respond to this threat with an even stronger organized resistance or if enough NGOs simply refuse to identify themselves as “foreign agents.” It will also fail if media outlets continue to criticize the regime without fear of criminal charges for defamation and if enough people — perhaps 70 or 80 percent — vote against United Russia and Putin to make falsification of election results a near impossibility. If these things happen, selective application of fines or even jail sentences will have no effect, and the authorities will rightfully shrink from applying repressive measures on a mass scale.

More Russians are realizing that the Kremlin’s “politics of fear” is a sign of its acute weakness and its instinctive fear of an open and transparent political system. When the policy of tightening the screws encounters open resistance from society, the last thread that the current authoritarian regime is hanging onto will be severed.

Vladimir Gelman is a professor of political science at the European University in St. Petersburg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.