All of the predictions that the authorities would tighten the screws on opposition leaders and on the protest movement after President Vladimir Putin's May 7 inauguration are proving true. The May 6 protests have become the Kremlin's "cause celebre" for the new crackdown, and the authorities are attempting to manipulate Article 212 of the Criminal Code on mass riots to jail protesters for up to 10 years and to intimidate the entire anti-Putin movement.

Thirteen people connected with the May 6 rally are in custody, including several who were not even at the demonstration that day. A team of investigators has been formed to question dozens, perhaps hundreds, of other activists and search their property. If convicted, they would join the ranks of about 40 political prisoners already serving terms in Russia today.

According to a June 18 article in Vlast magazine that cited unnamed sources, Putin has ordered the Investigative Committee, headed by his close ally Alexander Bastrykin, to identify and punish the perpetrators of the May 6 protest like the British authorities did after the August 2011 riots in London. Using Britain's anti-riot laws, more than 1,500 rioters were charged, several of whom received prison sentences of 18 months to eight years.

But there is nothing in common between the events in London, which were truly riots, and the protests in Moscow on May 6. The unrest in the London erupted among the lower classes in response to police violence. The rioters looted, set fire to homes, shops, cars and other property and attacked policemen with weapons. Five people died in the violence, and the government had great difficulty bringing the situation under control. The British authorities prosecuted people against whom there was strong and convincing evidence that they were involved in rioting and other acts of violence against police and others.

During the May rally in Moscow, however, there was nothing that would fall under the legal definition of mass riots used in the West or Russia. The "rioters" were, in fact, peaceful protesters, roughly 70 percent of whom had a higher education, according to polls taken at the rally. In an act of clear provocation, riot police left only a narrow corridor to Bolotnaya Ploshchad, the location approved by City Hall for the sanctioned demonstration, causing chaos and panic among hundreds of protesters as they were pushed back by police. It was this artificial bottleneck that led to isolated clashes between several unarmed protesters and riot police, but there was no riot, even under the most liberal definition of the word.

Article 212 of the Criminal Code on mass riots, which the authorities are trying to invoke against protesters, gives a clear definition of what a riot must entail: "violence, pogroms, arson, the destruction of property, the use of firearms, explosives or explosive devices, and also armed resistance to government representatives."

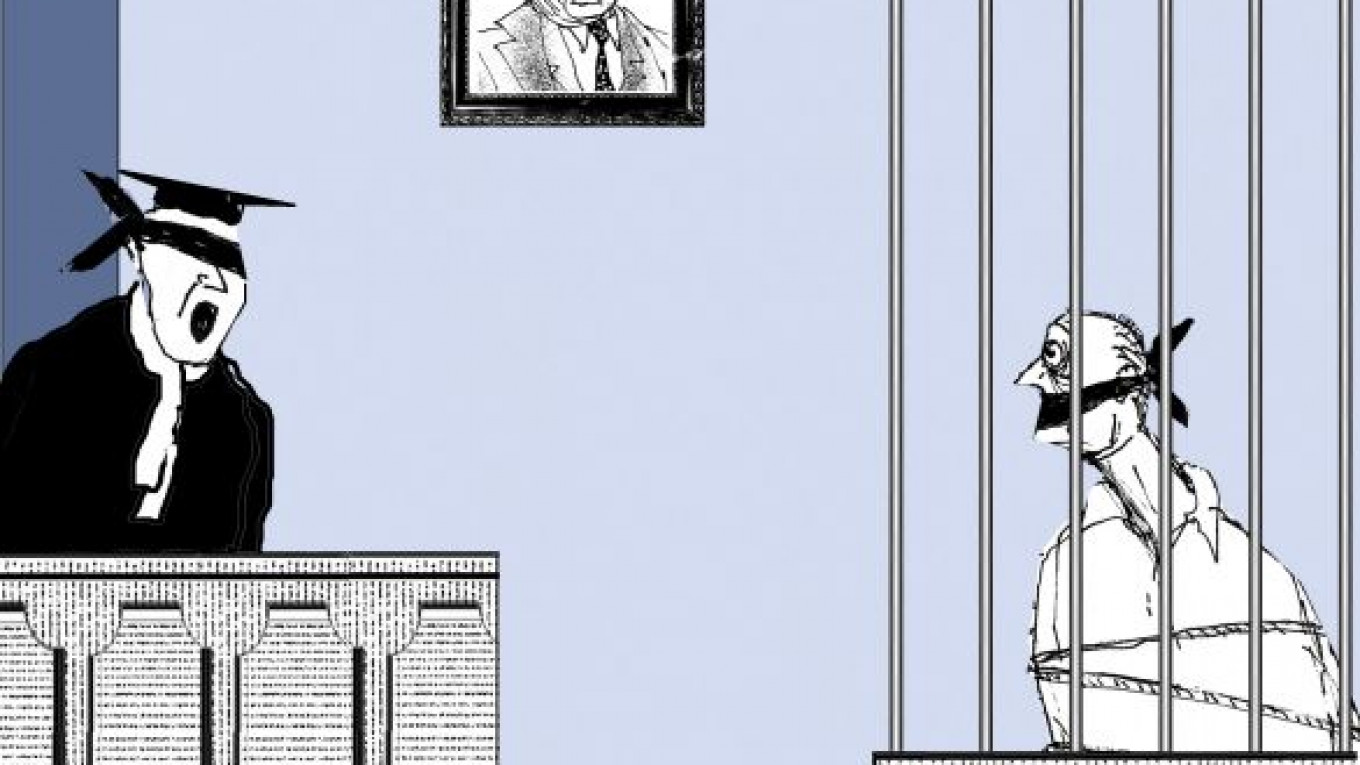

The authorities' decision to apply Article 212 against participants of the May 6 rally has set a dangerous precedent. It is also an underhanded trap. Now, peaceful protesters at a rally who are victims of unprovoked violence by police or provocateurs planted in the crowd could face prison terms of up to 10 years. The Kremlin has turned Article 31 of the Constitution completely on its head, effectively criminalizing citizens' constitutional right to assembly.

Another way to tighten the screws against the protest movement is manipulating Article 318 of the Criminal Code regarding the use of violence against the police. Riot police clad in heavy armor and helmets and armed with truncheons and steel-toed boots attacked protesters in T-shirts, shorts and sandals, who are later charged under Article 318. Meanwhile, judges refuse to view videos that prove the innocence of those detained. Instead, they accept the testimony of the riot police on blind faith and rubber-stamp one conviction after another.

It is clear that Putin is moving toward an even harsher form of authoritarianism. He is increasing the use of illegal arrests and searches, the cynical and unlawful interpretation of what constitutes a riot and violence against the police, and the reclassification of petty, administrative violations into criminal offenses. By doing so, he is coming into greater conflict not only with the people but also with the norms and obligations Russia must uphold as a member of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the Council of Europe.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition Party of People's Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.