Vladimir Putin's return to the Kremlin was always a foregone conclusion. But when he is sworn in on Monday, he will retake formal charge of a country whose politics — even Putin's own political future — has turned unpredictable.

Putin's return to the presidency, following a period of de facto control as prime minister, was supposed to signify a reassuring continuation of "business as usual" — a strong, orderly state devoid of the potentially destabilizing effects of multiparty democracy and bickering politicians.

Instead, the Russian people have now challenged the status quo. Their reaction to Putin's plan — from the announcement on Sept. 24 that President Dmitry Medvedev would stand aside for his mentor, to the deeply flawed parliamentary and presidential elections in December and March — and their accumulated resentment of Kremlin cronies' massive enrichment, has placed pressure on Putin and the top-down system of government that he created.

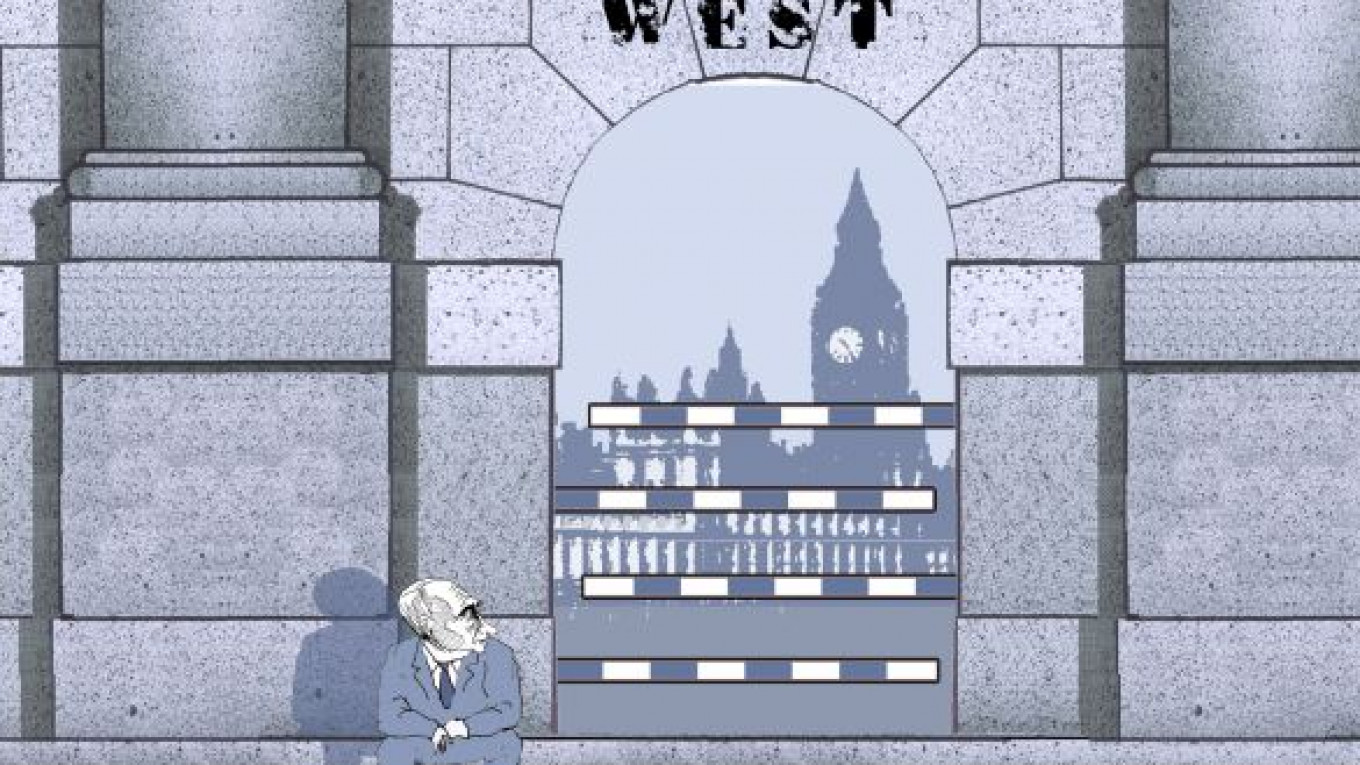

How Putin, an astute politician, responds to that pressure will determine his political legacy. And the West's response to Putin's return to the presidency could have a marked effect on whether he presses for liberalizing reforms and survives, or whether he will follow his KGB-honed authoritarian instincts and stoke further protest.

Nothing illustrates Russia's malaise under Putin better than the case of Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer working for Hermitage Capital. He uncovered a massive tax fraud and alleged widespread collusion by the authorities. His reward for exposing this crime was to be imprisoned and mistreated until he died in mysterious circumstances.

The U.S. Congress is currently debating a law that would impose asset freezes and visa bans on more than 60 people identified as having had some responsibility for Magnitsky's detention and death. Many of the law's supporters want it to replace the Jackson-Vanik amendment, a Cold War-era law that restricts U.S. trade with Russia. Such a change would be doubly beneficial: It would both enhance trade and hold to account people responsible for egregious human rights abuses.

Meanwhile, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office announced earlier this week strengthened immigration rules that would make it difficult for Russians accused of human rights violations in the Magnitsky case to enter Britain, a favorite destination for wealthy Russians. In Ottawa, the Canadian parliament has called for similar measures, including asset freezes against those responsible for Magnitsky's death, as has the European Parliament, which has called for the European Union's member states to take collective action.

Introducing such targeted sanctions would be an indisputable sign that the West will not compromise on its fundamental values — values that Putin's Russia claims to share. It would also set a precedent that could be extended to all of those in Russia and other countries who regularly violate human rights, and not just those rights concerning physical inviolability.

For example, such measures could be extended to cover all of those who abuse the fundamental right of legal due process, such as the right to a fair trial. This would highlight the case of former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky, whose political ambitions were the main reason he was singled out by the authorities and sentenced to jail, and who has been declared, after a second trial, a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.

Such measures could also include the abuse of prisoners' rights, such as the case of Khodorkovsky's former legal counsel Vasily Alexanyan, who was denied treatment for HIV during his 3 1/2 years in pretrial detention. After the European Court of Human Rights ruled in December 2008 that Russia had violated four articles of the European Convention on Human Rights in detaining Alexanyan, he was finally released in December 2009. (Alexanyan died in October as a result of complications from AIDS.)

Imposing travel sanctions and asset freezes on suspected human rights abusers is a sensible and practical way forward. It would show that the West does not seek to punish Russia or Russians generally, but only those individuals whose role in human rights violations the West has good evidence about. It would also remind Russia of its international legal obligations, specifically as a member of both the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the Council of Europe, which has 47 member states, including Russia and others who flout some of its conventions.

In the past, Putin successfully marketed himself as a strongman, the epitome of stability and a guarantor against chaos. But now Putin's style of government is Russia's primary source of instability. This is particularly seen when the country's middle class takes to the streets in protest against the corruption and inefficiency of his rule.

The West has an opportunity — and obligation — to convince Putin that protecting his own interests requires profound and permanent democratic reform in Russia, starting with an unambiguous commitment to the rule of law. And Putin has a rare opportunity, as he begins his third term as president, to restore his deeply tarnished reputation.

Charles Tannock is foreign affairs spokesman for the European Conservatives and Reformists Group in the European Parliament. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.