It has been nearly 60 years since Stalin's death, but interpreting his deeply complex legacy remains anything but academic.

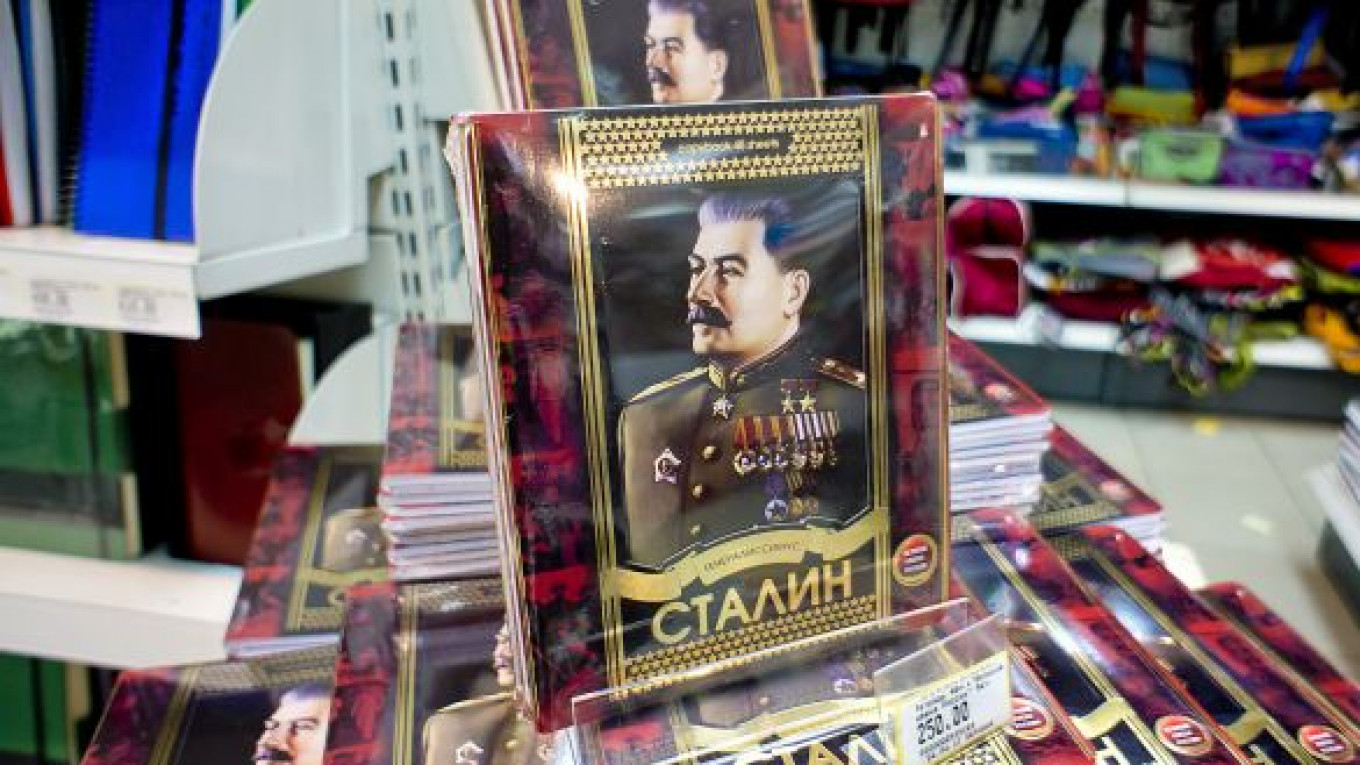

So when a local publisher released a simple student's notebook featuring Stalin's steely glare on its cover as part of a "Great Names of Russia" series, accusations of revisionist history flew, and the uproar quickly turned into a hot political topic and an international news story.

Artyom Belan, the artistic director for the book's publisher, Alt, said the reason they produced the book is simple — Stalin is a part of history and should be viewed with objectivity.

"Stalin was 60 years ago — 60 years. It is history. We relate to him as a part of our history, maybe a bad part, maybe a good one but nothing more," he told The Moscow Times on Thursday.

"I believe that we should relate to Stalin as English people do to Cromwell who ruled Britain for 10 years and undertook a very bloody movement," he added. "But he also made a lot of progress and there is a monument to him outside parliament."

But Alexander Cherkasov, a historian for human rights group Memorial derided the possibility of an objective simplification.

"You can say that although lots of people died [under Stalin], they also built factories and defeated Hitler but that's like saying, well, Hitler built autobahns!" he exclaimed.

A line from the book's text perhaps defines the fury best: "For some, Stalin is the offspring of hell, nearly Satan himself, for others he is the greatest leader of all time, a teacher and practically a saint."

Cherkasov insists that the short biography on Stalin presented in the book is simply not correct.

"The information in these books is categorically not true and for that reason alone, because of the unreliability of this information, they should not give these books to schoolchildren," he said. "You wouldn't give schoolchildren a book saying that two plus two equals five."

Belan admitted that he is not a historian but said the information came from "trustworthy" sources, which referenced official archives.

Meanwhile, the angry debate has fast become a thorny political football.

On Sunday, Public Chamber members Nikolai Svanidze and Sergei Volkov attacked the book as "a moral and ethical depravity" and "akin to Hitler's swastika," RIA-Novosti reported.

The next day, Public Chamber member and director of Moscow's school No. 548, Yefim Rachevsky, said Russians should treat Stalin like Germans treat Hitler.

"Such school books should not exist. Until an active policy of 'de-Stalinization' is started, we will trail behind the history of the world. We must do what the Germans did with 'de-Hitlerization'," he told RIA-Novosti on Monday.

Education Minister Andrei Fursenko says he is opposed to the notebook, but there is nothing he can do about it since it does not break any law.

"Anyone can publish whatever they like. Pornography is banned, Nazi symbols are banned. But who can ban everything else by law?" he said Tuesday, according to RIA-Novosti.

Many worry that an attempt at rehabilitating Stalin's image is underway, following other controversies like ex-Mayor Yury Luzhkov's effort to place billboards of Stalin in Moscow in 2010 to recognize his achievements as the commander of the Red Army in World War II.

The idea was eventually dropped amid uproar from human rights groups, but Stalin's portrait did appear on buses in St. Petersburg.

In 2008, Stalin was voted Russia's third-greatest historical figure in a TV show called "Name of Russia." More recently, a February survey by state-run pollster VTsIOM showed that 28 percent of Russians think Stalin ran the country well.

Irina Abankina, head of the Institute of Education Development with the Higher School of Economics, said she believes that a revival of positive opinions of Stalin is due to the passing of time but that society should continue to portray him in a negative light.

"It is extremely important that a universal opinion is formulated in any textbooks or history in general that such people who committed tyrannical crimes are shown to be tyrants," she said.

"Any positive relation to Stalin or Stalinism seems very dangerous to me," she added.

But Belan attacked this view, labeling the people who want to control how Stalin is presented as hypocrites.

"We live in a free country, and the people who are fighting the books most of all are those people who call themselves liberals and defenders of free speech," he said. "They are for freedom of speech but only for themselves and people who represent their same interests. If we have free speech, it is for everyone."

Belan denies that the attention the scandal has brought has been good for business.

"I have not been able to work for three days, I have been answering phone calls the whole time, I have given five television interviews," he said. "We have hundreds of books, but the whole country is just focusing on one. How can that please us?"

He did admit that sales have dramatically increased because of the controversy.

"We have a problem at the moment that there are 20 books in this series, but only the ones of Stalin are selling well! We want all of them to sell equally, though," he added.

The books, which are printed in Ukraine, are being sold in packs of five with those of other historical figures for 250 rubles ($8) per pack.

Svetlana Churilova, a 33-year-old metallurgist shopping for notebooks for her 6-year-old daughter Olga at Dom Knigi on Novy Arbat, said the Stalin book was the last thing she would buy.

"My grandparents lived under Stalin, and they had nothing good to say about him. I understand that this is a part of our history and I will tell my daughter about it, but she does not need to have this on her desk every single day," she said.

Last week, Orthodox Church spokesman Vsevolod Chaplin said works by Communist figures, including Vladimir Lenin, should be assessed for extremism.

Staff writer Lukas I. Alpert contributed to this report.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.