Is the Cold War over? Textbooks say yes and even cite the date that hostilities ended: Dec. 3, 1989, during the Malta Summit of Mikhail Gorbachev and President George H.W. Bush. But some doubts still remain — or have reappeared.

Today, leaders in Russia are playing their cards exactly by the Leonid Brezhnev playbook. Domestically they are whipping up anti-Western hysteria, accusing the West and its allies of various forms of "interference in Russia's domestic affairs" — mostly when voices in the West protest the repression of Russian opposition activists. The country continues to support an enormous army, and the defense budget is growing by leaps and bounds (its projected growth is 35 percent over the next three years). In foreign affairs, Russia, like the Soviet Union before it, is always ready to lend a hand to any rogue state on any continent. The fruits of its "cooperation" with Iran, Syria and North Korea are a diplomatic headache for the rest of the world.

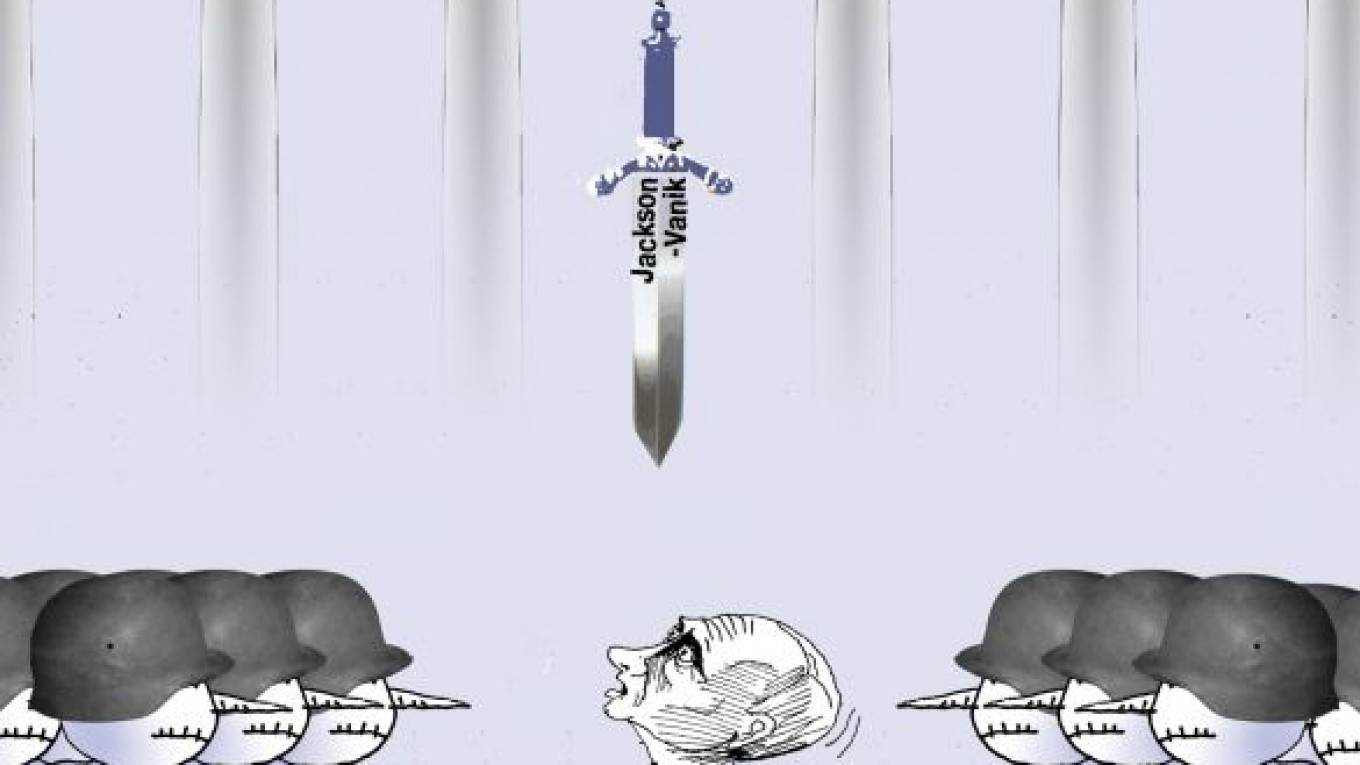

The spirit of the Cold War doesn't only permeate the tough talk of President-elect Vladimir Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. It is also reflected in the heated debates about a relic of the Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan years — the Jackson-Vanik amendment. Passed by the U.S. Congress in 1974, it forced Soviet leaders to undertake a minimal liberalization of the regime. The amendment opened the door to mass emigration from the Soviet Union and helped hundreds of thousands of people escape repression, join their relatives abroad or simply leave behind inhuman living conditions.

The Kremlin hated the Jackson-Vanik amendment because it prevented the Soviet Union from receiving American loans and the technology needed for the defense industry. But there were also critics of the amendment in the United States. In the mid-1980s, after Gorbachev came to power, the amendment was discussed on Capitol Hill. Opponents argued for the law's repeal on the basis that it did not facilitate greater democracy and hampered trade relations. The campaign continued until Soviet dissident Nathan Sharansky was released from prison and arrived in the United States. Sharansky argued strongly against repealing the amendment, insisting that it would put the nascent Soviet reforms at risk.

Since 1989, there has been a moratorium on the amendment's provisions, which makes the Kremlin's fury over a purely symbolic act all the more puzzling. And then, politics makes for strange bedfellows. Suddenly the Kremlin found allies in its own opposition. On March 12, The New York Times published a report about a letter by seven people named "leaders of the opposition" in Russia — although only four of them are activists — calling for a repeal of the amendment since "Jackson-Vanik is also a very useful tool for Mr. Putin's anti-American propaganda machine: It helps him to depict the United States as hostile to Russia."

Alexander Podrabinek, a veteran human rights activist, responded ironically on his blog, saying, "The mutual understanding between two governments and some Russian oppositional 'figures' is so touching!" Former Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov, who signed the letter, quickly explained that he doesn't support the repeal of Jackson-Vanik. He wants to replace it with the Magnitsky act, which would introduce sanctions against individuals involved in human rights violations and corruption.

But the historian Alexander Goldfarb thought that the opposition leaders made a mistake and had let themselves become pawns in someone else's political game. On his blog, he wrote: "The Senate is slated to discuss the Jackson-Vanik amendment, not the 'Magnitsky list.' Even if someone brings it up, it doesn't make any difference. They are discussing only a repeal of the amendment." Fortunately, nothing changed. A Senate Finance Committee hearing on March 15 left the status quo.

Why the Kremlin needs the repeal of Jackson-Vanik is obvious to anyone. As blogger Arifg wrote, "As long as it is not repealed, it hangs like Damocles' sword over the heads of the crooks in power, since the moratorium might be lifted at any moment if the human rights situation in Russia gets worse."

But it's harder to understand why Washington officialdom is lobbying so hard for the repeal. It may be a futile attempt to resuscitate the political reset from a permanent coma, or there may be some other realpolitik considerations hidden from view. One can only speculate.

History has shown that Nathan Sharansky was right. As Goldfarb writes, "You can only talk with the Kremlin in the language of sanctions." Today when Russian citizens are once again compelled to go out onto the square and defend their rights, keeping the Jackson-Vanik amendment is the best way the United States can support them.

Victor Davidoff is a Moscow-based writer and journalist whose blog is

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.