During the March 4 presidential election, I along with the observers for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe monitored more than 1,000 polling stations. This is a considerable number, but in the whole country there were nearly 100,000. Much more important was the role that the domestic observers played this time around. Following the problems in the December State Duma elections and the mass protest demonstrations that followed, many new people volunteered as observers. On election day, representatives of the candidates in the race were present in 95 percent of polling stations and many of them proved to be attentive, active and informed.

Voting on election day was assessed by our observers as "good" and "very good" in 95 percent of polling stations visited. Minor delays in opening were noted in 20 percent of polling stations observed. But the process deteriorated during the counting of the ballots, which was assessed negatively in almost one-third of polling stations observed — mainly due to procedural irregularities.

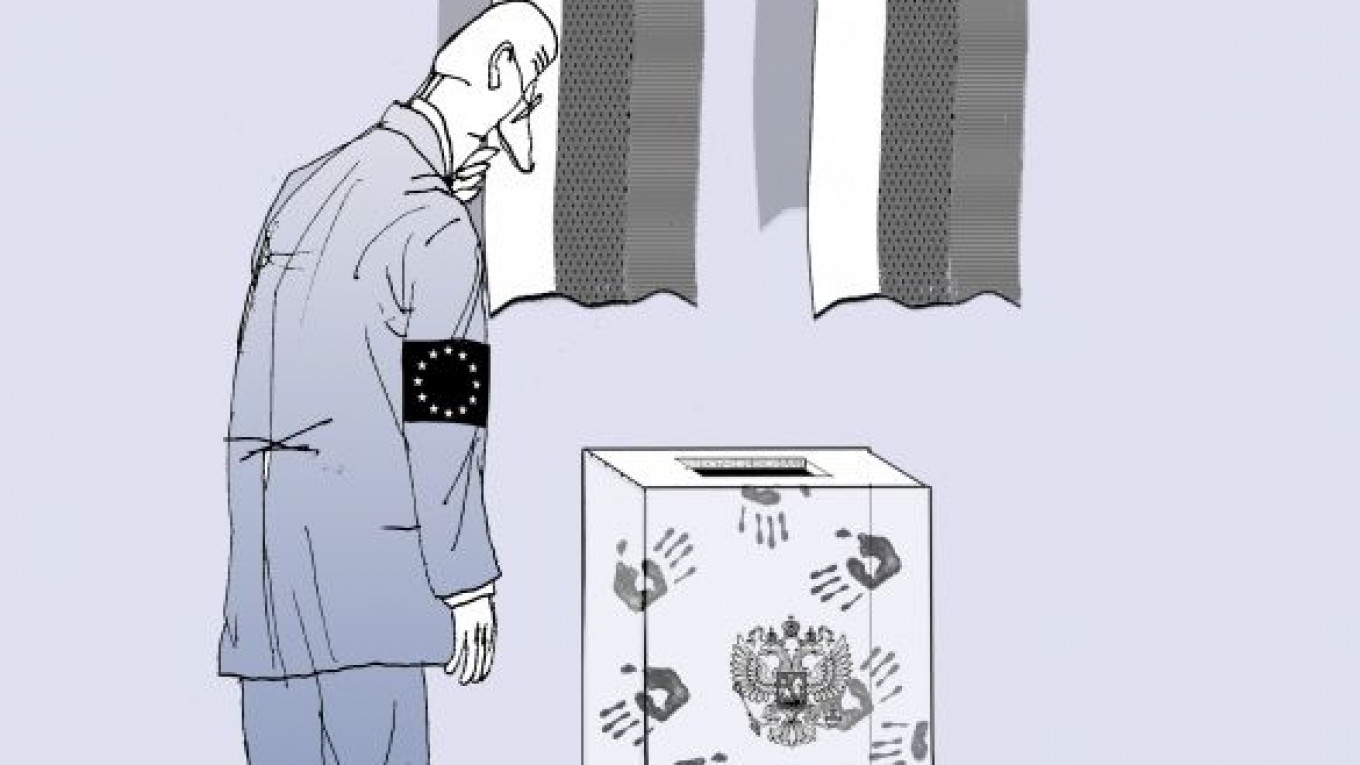

Of 98 counts observed, 29 were assessed as "bad" and "very bad." There were a few instances of ballot box-stuffing and some indications of buses transporting groups of voters to vote at multiple polling stations. In 21 polling stations where we observed the count, completed protocol results were not shown to web cameras as required, and results were not read out loud in 18 cases. The signed protocol was not posted in 31 polling stations observed. The tabulation was observed in over 70 territorial elections commissions, and the process in 11 of them was assessed as "bad" and "very bad." In these cases, we saw poor organization of data entry, overcrowding, insufficient transparency and instances of changing in protocols by territorial elections commissions. Formal complaints were filed in 4 percent of polling stations observed.

International observers are not interested in who wins but the process in which candidates are elected. The election of Vladimir Putin was no surprise nor seriously challenged. Most domestic observers concluded that in any case, Putin got the support of the majority of the citizens who cast their vote on March 4. But the fact that the winner is not disputed does not make the election indisputable. On election day, the vote count often did not correspond to protocols.

Mistakes are always possible, but manipulation is never pardonable and is an insult to the voters. When I read a comment from our former colleague Sergei Markov, former Duma deputy from United Russia who now is a political analyst, that "Putin is clearly supported by the majority, and only about 2 percentage points may have been added to Putin's vote count by overzealous officials in the regions," it must be clear that this is, in any case, 2 percent too much and completely unacceptable in democratic elections. Other comments mention far higher percentages and cast doubt on the real election result.

More important, the electoral process did not meet the standards of a fair and transparent competition. The choice for the voters was limited, some candidates had been excluded because of overly rigid rules, and the playing field for the candidates was by no means level. Putin received a much larger share of the media attention, and administrative resources were used to his electoral benefit. Not to mention an impartial election referee was sorely missed. The way in which chairman Central Elections Commission chief Vladimir Churov operates is part of the problem, not part of the solution. Without a trusted impartial elections commission, every election's result will be disputed.

The good news is that improvements were also made on March 4 and before. For example, there were transparent ballot boxes in many polling stations and web cameras in all voting stations on election day. There was better media access for all candidates in the weeks before, as well as freedom of assembly for those who demanded fair elections. Many mass rallies took place in a peaceful atmosphere. Furthermore, participation in parliamentary and presidential elections will become easier in the future if the Duma agrees on the laws proposed by President Dmitry Medvedev. The recent agreement on the restoration of the Republican Party after the 2011 verdict of the European Court of Human Rights is also good news. Introduction of a new public television network could further improve media access to participants and help to develop a more level playing field.

But more is needed, including a thorough reform of all the local and central elections commissions, and strict rules on the use of administrative resources in campaign periods. As for now, one of the main positive results of Russia's elections is the far greater involvement of citizens and their demand that elections should be transparent and fair. This is a clear enrichment of Russian democracy. Maintaining this level of citizen involvement should be a priority for everyone who plays a role in Russian politics.

Tiny Kox is head of PACE's elections observation mission.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.