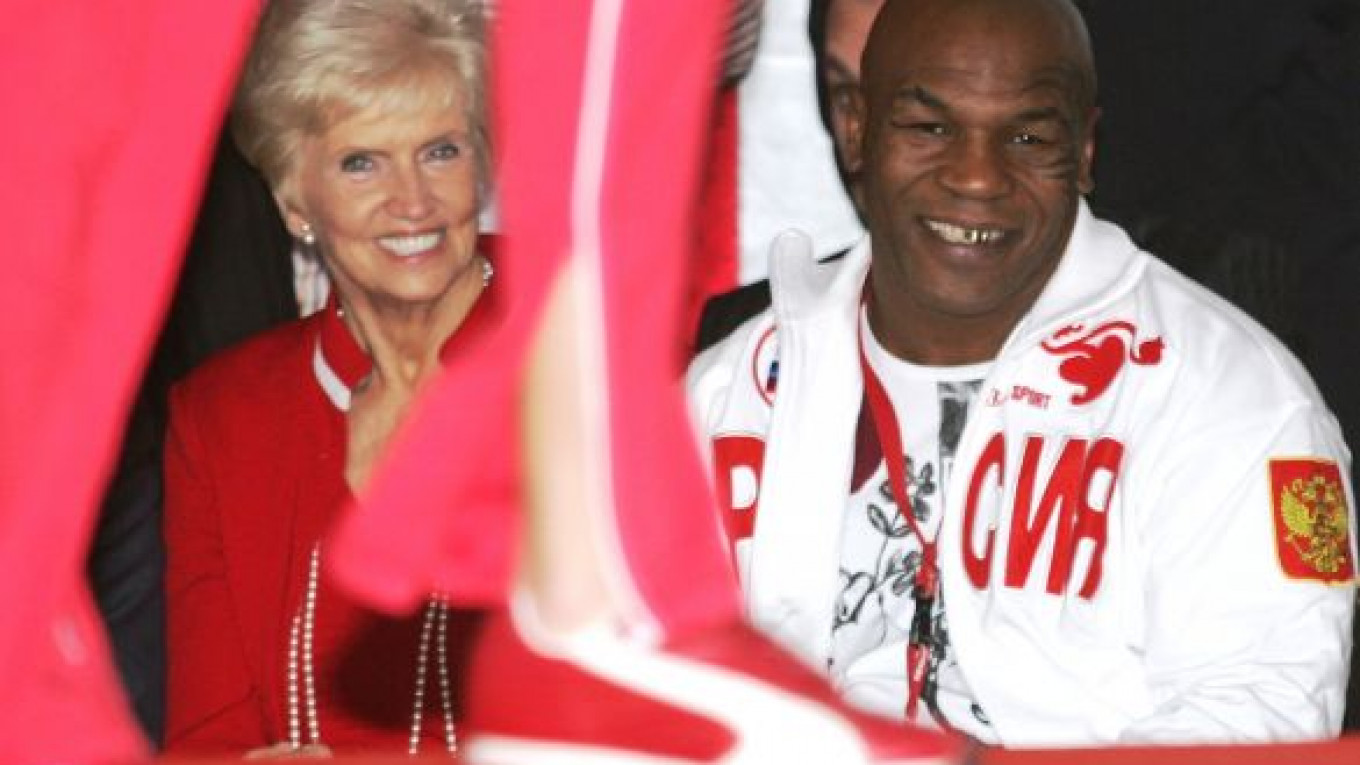

There is only one person in the world who boxing legend Mike Tyson calls "Mom" — and she's not his biological mother, who died when he was 16. The title goes to Marilyn Murray, a U.S.-born descendant of Russian immigrants who is also a scholar of the Russian mind.

Tyson turned to Murray, a psychotherapist, following his 1995 release from prison, where he served three years for rape. But after working with him for several years, Murray faced a dilemma: While Tyson was starting to get serious about getting healthy, she was beginning to work in Russia and could no longer be his therapist.

"At this time he didn't have a lot of healthy, balanced people around him, so I began introducing him to people whom I knew, including other professional athletes, and also to the members of my family," Murray said. "Our relationship began to change. He started to participate in various events with my family and began introducing me as his mom."

Education

1985 – California State University (Sonoma, California), master’s in psychology

1983 – Ottawa University (Phoenix, Arizona), bachelor’s in psychology

Work Experience

1984-Present: educator, therapist, theorist, The Murray Method professional training and workshops, United States and other countries

2010-Present: professor, Institute of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Moscow

2004-08: guest professor, Moscow State University of Psychology and Education, Moscow

1968-84: Art dealer, Scottsdale, Arizona

Author of two books, “Prisoner of Another War” (1991), available in Russian and in English, and the forthcoming “The Murray Method” (2012), which will be published in Russian and English.

Favorite book: Bible

Reading now: “Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy” (1996) by Dmitry Volkogonov (this is my 10th book on Stalin)

Favorite Moscow restaurant: Trattoria-Venetsia, 4/3 Strastnoi Bulvar

Weekend getaway destination: I don’t do weekend getaways, but I recently took a 15-day trip on the Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express from Moscow to Vladivostok.

Murray, who met informally with Tyson during subsequent trips back to the United States, described him as "very different" from how most of the world sees him — a person who can be shy and sensitive, polite and protective. "He also has an enormous interest in Russia," she said. "When I would return to Arizona from Moscow, we would usually spend some time together. He would often say, 'Mom, I want to come to see you in Russia.'"

Murray said she never believed that he would actually come to Russia, but in 2005, he arrived and stayed two weeks.

"It was an amazing time, with crowds of people of all ages following us everywhere we went," she said. "There were numerous pictures of us in The Moscow Times and other papers, and on television. I deliberately did not give journalists my name, so everyone reported that Mike Tyson was accompanied by an unidentified woman. That lady was me."

While she sought anonymity during Tyson's visit, Murray is not unknown.

Murray, 75, first made a name for herself in the 1970s as a businesswoman who co-founded the first major arts gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, a city now known as a regional art center with more than 100 galleries. Murray also grew interested in countries behind the Iron Curtain when she joined a group from her local church in spiriting U.S. dollars into Czechoslovakia to give to needy people.

In the 1980s, Murray confronted sexual abuse from her own childhood and sank her heart into psychology. She developed a pioneering therapy and treatment model for trauma — the Murray Method — that has been embraced by organizations in the United States and elsewhere. Murray also worked pro bono for six years with incarcerated U.S. sex offenders and wrote an autobiography.

She moved to Moscow in 2002 after Russian therapists and clergy told her that they lacked training on trauma, abuse and neglect in a country that had long denied that those issues existed and that they found her Murray Method seminars particularly useful. Her students learn by applying the coursework to their own lives.

"I always say you can't ask your clients to do something that you haven't done yourself," said Murray, president of the Murray Method International Center in Moscow. "I require the same thing in the United States."

Thousands of hours of classes have provided Murray with a rare insight into the Russian psyche that she will share in an upcoming book, "The Murray Method," and a weekly Moscow Times column that will debut Tuesday.

Of the 2,000 people whom Murray has taught in Russia, many of her male students were attracted by her connection to Mike Tyson. "I have had numerous men who said they came to my classes because someone told them that Mike had come here to Moscow to see me and that he regards me as his mom," Murray said. "They figured that if I could work with Mike Tyson, I could work with them."

Q: Why did you come to Russia, and why have you stayed?

A: My father's parents were born in small villages near Saratov on the Volga — my grandfather in 1858 and my grandmother in 1866. But when, as a child, I would ask my father about his childhood, he would simply say, "It is too painful. I don't want to talk about it." When I would ask my mother, she would say they had tried to contact my father's family members left in Russia but were never able to get through.

Then in 1996, I received a package with my father's family tree from a cousin I never knew existed. When the Soviet system collapsed in 1991, this cousin was able to contact a professor in Saratov and paid him to research our family history by going through old birth, marriage and death records in an archive in Engels in the Saratov region. When I learned that my grandfather's family had lived in a village named Talovka since 1767, I started to cry. It was like I had found half of my life that I didn't know existed. The big shock was that I had always been told — and my father had died believing — that he was the youngest of seven children. But I found from this chart that he was actually the youngest of 12, and five siblings, that he didn't even know existed, had been born and died here in Russia.

In 2002, when I was asked to teach one week of a six-month addictions program in Moscow, I was eager to accept. When I finished, many people said, "We really need you. Fortunately we now have several people teaching us how to treat addictions, but no one is helping us learn how to deal with trauma, abuse, neglect and all of the pain that we have been carrying in Russia for centuries." They begged me, "Please, will you stay?" So I did.

During that first trip in 2002, I also went to Saratov for eight days. I visited both my grandfather's and my grandmother's villages and saw where my family had lived for more than 200 years. It was a very powerful time for me, especially since I had learned that every single member of my family had been brutalized by the Soviet system. Some died of starvation during the '20s and '30s, and others were killed outright. One of my father's uncles was the mayor of Talovka, and in 1931, when the Soviets implemented forced collectivization and demanded all the village's grain, he said, "If I give you all the grain, everybody will die of starvation." They buried him alive. One of his sons was shot, and another was beaten to death. Two daughters were sent to the gulag. When I heard these things, it touched my heart and confirmed that I needed to be here, that this was home for me.

Why have I stayed? Russia truly feels like home. I have many close friends and colleagues here. I also am a history buff and, having owned an art gallery for years, am very interested in art. I just visited the Tretyakov Gallery for the 15th time. If you are interested in culture and art and history, there is no place like Russia.

Q: What qualifies you to speak as an expert on the Russian mind?

A: The Russian personality is so complex that it would be inaccurate to say anyone was an expert. But I will say this: What qualifies me to speak as somebody learning to understand the Russian psyche is the fact that I have taught about 2,000 students in 117 classes over 10 years. The students work on painful issues from their childhoods and adult lives, and they share things that they say they have never shared with anyone else before, not even their closest loved ones. I regard this as a very special honor and I deeply respect their courage and willingness to address so many issues that were always regarded in the past as "the unspeakable."

I do not address issues of Russian politics, business or ecology because I don't specialize in these areas. But when it comes to the Russian mind and why people do what they do, this is my field of study — and not just in Russia. I have students from 37 countries, and researching why people act and react in a certain manner is greatly intriguing to me.

Q: What should foreigners know or understand about Russians?

A: There are many answers to this question, and I will attempt to address some of them in my future columns. One of the more obvious responses concerns priorities — for Russians, relationships and communication are very important, while Americans value responsibility and being organized, among other things.

Here's an example that made me laugh. In one of my classes, the students put on a skit about how Russians and Americans prepare for conferences. First they acted out the part of the Americans, sitting down at a table with their briefcases a year before the conference was to open. Every person was assigned a responsibility: one for the program, one for the advertising, one to locate a facility, and so on. After the initial meeting, the group gathered regularly for follow-up planning, and, of course, everything was ready when the conference opened.

Then the students said the Russian way would be like this: The conference is scheduled for Monday, and on Thursday or Friday before the event the organizers have tea and one says, "You know, I think we are having a conference on Monday. Has anybody found a place where we could have it, and who do you think would want to come and speak?" It was like they were sitting there, talking, laughing and enjoying each other's company, and the conference became wedged in between other conversations.

In work negotiations, an American will probably come to a meeting and immediately get down to business — usually checking the clock to make certain everything is running on schedule. He also expects to have timely follow-up meetings in which both sides come prepared to negotiate a deal. But when a Russian is in charge, he might sit down and say, "Tell me about your family. Do you have any children? I have two children and a new grandson. Do you have any grandchildren? Here have a drink. Please leave your paperwork with us and come back in three or four months and we will talk some more. Maybe then you can go to banya with us. After that, we can sit and talk and perhaps you can show me some pictures of your family. Here, have another drink …"

The No. 1 thing that a foreign investor should know is that negotiations are going to take a long time and chances are that even if you reach an agreement, it usually will not turn out the way you planned. No matter how much the other party promises something, the chances of the promise materializing exactly as you expected are pretty slim. I have found this out for myself, and many of my Russian students admit this regularly happens to them too.

Q: What issues keep you up at night?

A: None. I have worked in the field of trauma for 30 years and have had to learn that I can't carry my clients' or students' problems. When I go to bed at night, I say, "Lord, here are these people, and their issues. I know you love them, and I trust you will be responsible for them."

When it comes to problem issues, many people would be surprised about the amount of trauma, abuse and neglect that nearly every person has experienced here. When I listen to people tell their stories and I think I have heard absolutely the worst thing possible, I hear something even worse in the next story. That's saying a lot for someone who has worked with many people with serious abuse issues in the United States. No Russian family has been protected from World War II, gulags, repression, starvation, famines and similarly horrific things.

Part of my research for the past three decades concerns how our defense mechanisms enable us to survive. Have you wondered why the alcoholism rate is so high in Russia and drug use is growing? Alcohol and drugs are major defense mechanisms used to drown pain. Unfortunately, high substance abuse also exacerbates violence — domestic violence and street violence in general. I have found violence to be higher here than in the West.

Q: What advice do you offer people living in Moscow on how to live healthy balanced lives?

A: My Russian students have shared with me that under the Soviet system they had no worth as a person — that they were only a cog in the wheel that made the state run. One of the most important issues that we constantly address in our classes is to help each participant realize that they are unique and valuable. I know that having a personal value system that is based upon love and respect for God, self and others, and also having a commitment to being balanced — physically, emotionally, intellectually and spiritually, and in relationship with God, or your Higher Power, and other people — will result in a life of inner peace and joy despite outside circumstances.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.