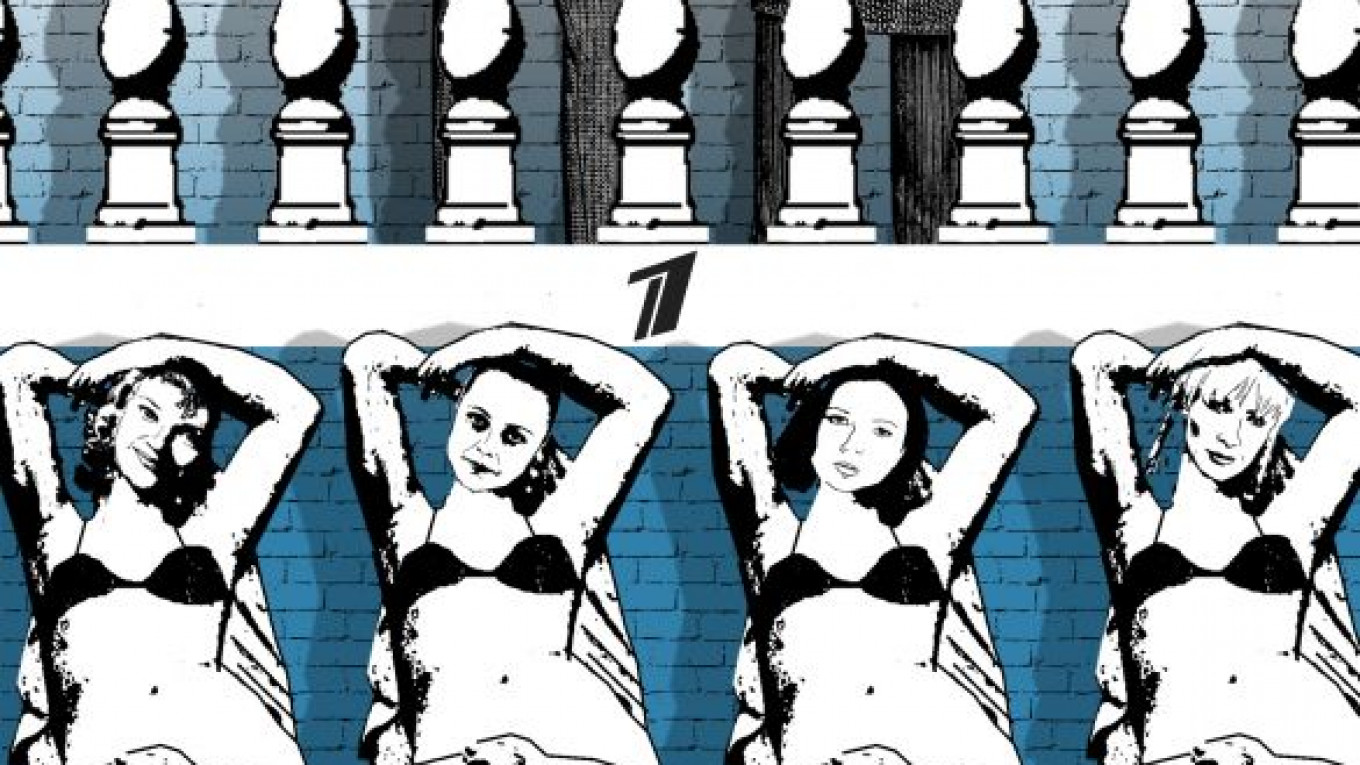

This week, Channel One began showing "A Short Course in Happy Life," a much-anticipated new drama from Valeria Gai Germanika, the director of the hugely controversial and popular "School" series.

That Channel One series in 2010 made school a hot topic, showing sex, violence, alcopops and alienation. It horrified some, but got a lot of praise for its fresh approach.

Gai Germanika's next television project was announced a long time ago, but has apparently been delayed. "A Short Course in Happy Life" tells the story of four women who work together in a sleek office and seem to be doing well in their careers, but whose personal lives are all at a crisis point.

Sasha is a single mother sleeping with her married boss. Lyuba tolerates her tipsy, though attractive husband, but he's failing to support her plans for fertility treatment. Katya is utterly taken for granted by her husband and is secretly jealous of her 14-year-old daughter's sex life. And Anna is a sweet singleton naively wandering into encounters with unsuitable men — including Sasha's ex-husband.

The concept has been compared with the U.S. show "Sex and the City," but while Carrie and Co. are buoyant about ultimately finding the "one," this late-night show is much darker. Its title comes from a self-help course in female empowerment that Sasha attends — until her resentful mother comes along and tells a confessional session that her daughter is a "slut."

The show has the same choppy camera angles as "School" and some of the shock value — it's not often Channel One airs a masturbation in the shower scene or a teenager telling his 14-year-old girlfriend: "Next time, I want to try using my tongue to make you come." But somehow with a story line about adults, it felt less daring.

Some of the details seemed just right, such as Katya's claustrophobic apartment where the dog hovers constantly, needing to be walked, and music throbs from her daughter's room. And Lyuba makes a recognizably horrible visit to her wealthy friends' newly built country house, where she has to admire the free-standing glass fireplace and everyone politely ignores the fact that one of their friends is drinking herself to death.

The female owner manically wipes fingerprints off the mansion's shiny surfaces.

"You're like a robot, you just wipe things constantly," Lyuba upbraids her.

I also liked Svetlana Khodenkova as Sasha, with her witchy eyes and wild hair. She recently starred in a disappointing remake of the Soviet classic "Office Romance" as the confirmed spinster boss who finds love with a colleague, where she was far too demure and weepy for someone who had apparently climbed the career ladder. In this show, she plays a similar role much more convincingly, moaning about PMS and terrifyingly putting down a man who complains about her parking.

But some of the scenes were a little bit too close to Russian television's standard depiction of women — spending a lot of time taking off their tops and crying about men. The downbeat mood also reminded me of late Soviet cinema with its constant theme of hardy, intelligent women desperate to get married to any man whatsoever. Each episode even opens with a quote from Joseph Heller about how women are sadder and less cute after the age of 25.

Also so far the male characters are pretty interchangeable, with uselessness and unreliability being their main characteristics. To underscore this, three of the husbands and lovers even look a lot like each other physically.

"You're all bitches," Sasha sneers at her lover.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.