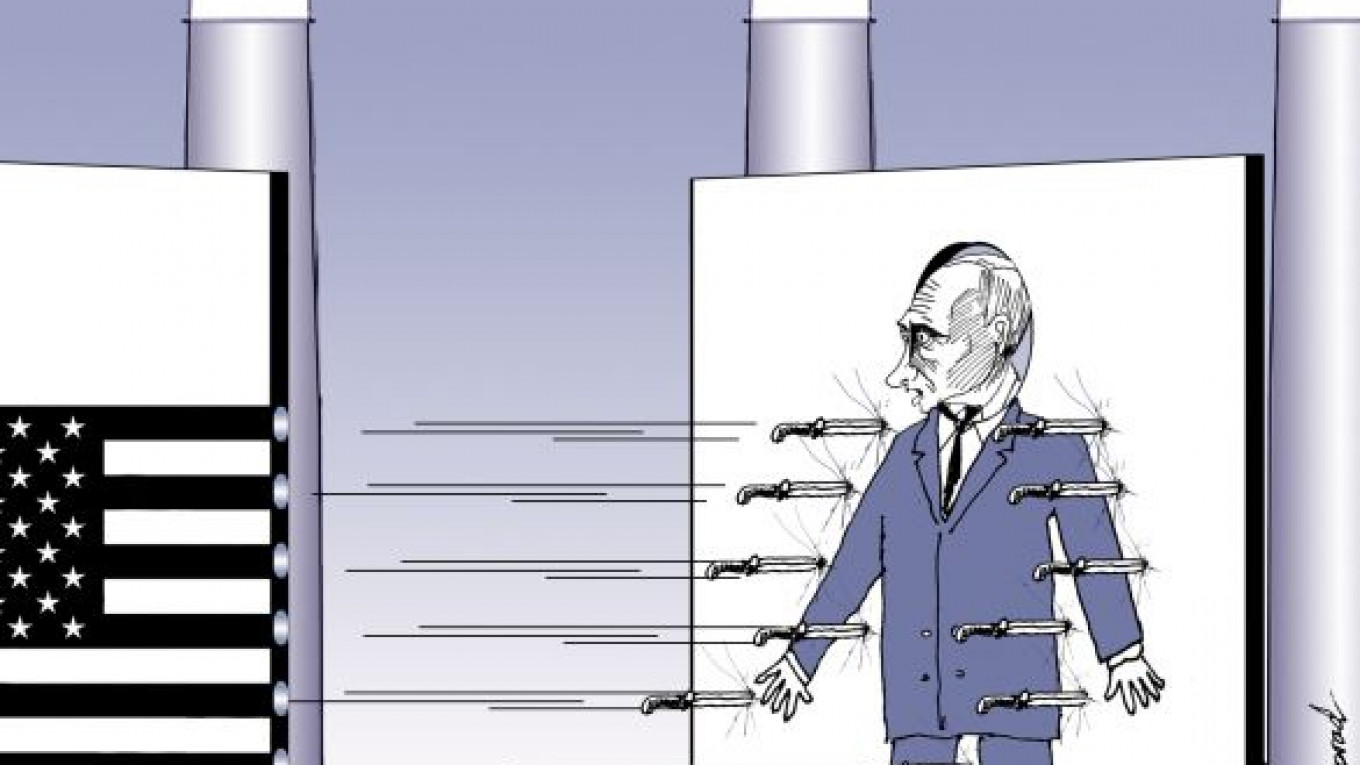

Here we go again — another round of anti-Americanism from the Kremlin and state-controlled media. We have heard claims that the United States is trying to orchestrate an Orange Revolution in Russia many times before, but it was never this intense.

Prime Minister Vladimir Putin sent the first signal in late November when he called Russians who receive certain foreign grants "Judases" and said it is necessary to strengthen the punishment for Russians "who carry out the orders of foreign states." A week later, Putin claimed that U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton instigated the opposition protests.

The gambit seemed to work. A Levada survey held shortly after showed that 23 percent of those polled believed that the protesters were paid by the United States, while 47 percent had difficulty answering.

Putin has taken a page from the Soviet period, when sharp criticism of the ruling regime was tantamount to perfidy. Remember how the Soviet mass media carried out a brutal campaign to discredit dissident Natan Sharansky. He was then sentenced to 13 years of forced labor in 1977 on false charges that he was a U.S. spy.

Mikhail Leontyev, host of the "Odnako" program on Channel One, picked up on Putin's cues in his Jan. 17 show, implying that U.S. Ambassador Michael McFaul has been sent to Moscow to carry out an Orange Revolution. McFaul has a perfect background for this mission, Leontyev said. After all, McFaul's academic specialty is revolutionary movements and democracy, and he even wrote a book with the suspicious title "Russia's Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin."

If that were not enough, 20 years ago McFaul worked as a senior adviser to the National Democratic Institute, a U.S. nongovernmental organization that is "well known for its close ties to U.S. intelligence organizations," Leontyev said.

On the same day, a short clip titled "Receiving Instructions From the Ambassador" attracted nearly 1 million views on the Internet. As opposition leaders, such as Boris Nemtsov and Vladimir Ryzhkov, and human rights activist Lev Ponomaryov were filmed approaching the U.S. Embassy on Jan. 17, they were each asked by NTV reporters: "Why are you coming to see the ambassador? What is your goal?"

Yet dual-track diplomacy — meeting with leaders in power as well as the opposition — is an established norm all over the world. Incidentally, Russian diplomats in Washington meet with prominent Republicans when there is a Democratic administration in the White House and vice versa. (The only thing that is prohibited in both countries is the direct foreign financing of political parties and candidates.)

Take, also , the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation, a Russian NGO located in New York that monitors human rights violations in the United States — clearly an attempt to give the United States a dose of its own medicine. The NGO's U.S. office is headed by Andranik Migranyan, a prominent political analyst. Claiming that the U.S. National Endowment for Democracy is fueling an Orange Revolution in Russia has about as much credibility as claiming that Migranyan's NGO is destabilizing the United States.

Then, on Feb. 3, we learned from NTV's tabloid program titled "The West Will Help Them" that McFaul is known as the "architect of Orange Revolutions" and that Alexei Navalny was recruited to Yale University's World Fellows Program to train him for his future mission: to fight the Putin regime.

During this program, we were also told that the high-sounding missions of U.S.-funded nongovernmental organizations — "defending human rights and building democracy" — is only a cynical decoy. So is the "reset," McFaul's brainchild. All of this "technology," developed in Langley and Foggy Bottom, is a prime example of the United States' subversive "soft power" that helps destabilize its enemies and execute regime change. The beauty of soft Orange Revolutions, political analyst Vyacheslav Nikonov said in the program, is that they are cheaper than war, leave fewer footprints and can achieve the same goals.

Finally, there was a high concentration of anti-American bile at the pro-Putin, Anti-Orange rally a week ago at Poklonnaya Gora. Political analyst Sergei Kurginyan screamed from the stage: "We say 'No' to the American Еmbassy, where they [opposition leaders] flock to the water trough like cows. Let's throw out this 'orange trash.'" Political analyst Alexander Dugin also screamed from the podium, saying the United States employs a "fifth column" of agents and spies within Russia and wants to take control of its rich natural resources.

Over the past few weeks, Kurginyan and Dugin, along with nationalist journalist Alexander Prokhanov and Leontyev, have jumped from one popular political talk show to another on state-controlled television spewing this anti-U.S. demagoguery.

Meanwhile, Alexei Pushkov — host of the analytical television show "Postscriptum," known for its critical views on U.S. foreign policy — has been appointed to chair the State Duma's high-profile International Affairs Committee, while Dmitry Rogozin, also known for his hawkish views on the United States, was promoted to deputy prime minister.

Rogozin shocked many in a Jan. 19 interview on Ekho Moskvy when he described with a serious expression on his face a scenario in which the United States could launch a simultaneous, "lightening-speed, massive and paralyzing" missile attack against all of Russia's land-based nuclear weapons. This would not give Russia a chance to respond with a counterattack — except, perhaps, for a few submarine-based missiles, but these would be easily intercepted by even a modest U.S. missile defense system. This type of Cold War hysteria takes us back to the apocalyptic year of 1983, if not 1962.

The notion that the United States orchestrated Ukraine's Orange Revolution in 2004 is just as ridiculous as the idea that the CIA orchestrated the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Similarly, the suggestion that Washington is orchestrating — or is even capable of orchestrating — an Orange-like Revolution in Russia is equally absurd.

Why, then, is the Kremlin chasing imaginary American ghosts? First, there is no other country that can fill this spot. China is out of the question because inflating tensions with its neighbor is too dangerous. On the contrary, as the recent UN Security Council veto on Syria showed, China can be a valuable Russian ally to help defy the United States. Islamic radicalism is also not an option because that would throw a match into its own North Caucasus tinderbox.

But attacking the United States is much safer. It is far away, and Washington usually just ignores the bluster about U.S. plots as they do when Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez pulls the same antics.

Second, the old trick of trying to smear the opposition and nongovernmental organizations as a U.S.-funded fifth column still works on millions — particularly among blue-collar Russians, a strong Putin constituency, for whom state-controlled television is still their primary source of information.

Blaming outside forces for Russia's woes has a long history in the country and has few limits, it would seem. Even the Fobos-Grunt failure, like the Kursk sinking in 2000, was first blamed on U.S. sabotage. The closer we get to the March 4 presidential election, the more intense the anti-American hysteria becomes.

Putin has picked up where the Soviet Union left off, but this tradition of blaming others goes far beyond the Soviet period. In an 1898 letter to publisher Alexei Suvorin, Anton Chekhov wrote: "When things are not going well in Russia, we always find someone else to blame: the Jews, [German Emperor] Wilhelm II, the French … anyone except ourselves."

Indeed, things are not going very well for Putin and the Kremlin: falsified elections in December that will likely have to be repeated on March 4, sinking popularity, a political crisis, Syria and mass protests that are bound to continue throughout 2012.

The United States is to blame for all of this. Sounds convincing.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.