The history of successive authoritarian regimes in Russia reveals a recurring pattern: They do not die from external blows or domestic insurgencies. Instead, they tend to collapse from a strange internal malady — a combination of the elites' encroaching disgust with themselves and a realization that the regime is exhausted. The illness resembles a political version of Jean-Paul Sartre's existential nausea and led to both the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the Soviet Union's demise with Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika.

Today, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin's regime is afflicted with the same terminal disease, despite — or because of — the seemingly impermeable political wall that it spent years constructing around itself. Putin's simulacrum of a large ideological regime simply couldn't avoid this fate. The leader's "heroic image" and "glorious deeds" are now blasphemed daily. And these verbal assaults are no longer limited to marginal opposition voices. They are now entering the mainstream media.

Two events have sharply accelerated the collapse of confidence in Putin's regime, both among the elite and ordinary Russians.

First, in September, at the congress of Putin's political party, United Russia, Putin and President Dmitry Medvedev formalized what everyone anticipated, with Putin announcing his intention to return to the presidency in March and thus virtually declaring himself Russia's dictator for life. His quest for eternal rule is driven not so much by a thirst for power as by a fear that he will one day be held accountable for his actions.

The second lethal blow to Putin's prestige came with the unprecedented scale of fraud perpetrated in December's parliamentary elections. According to reliable observers, such as the election-monitoring Golos and Citizens' Watch, vote-rigging in favor of United Russia resulted in a 15 percent to 20 percent advantage for what is now commonly called the party of "crooks and thieves." And the trickery began long before voting day, when nine opposition parties were prevented from even appearing on the ballot.

These two events have rendered Putin's regime not only illegitimate, but also ridiculous. Even if the regime formally wins the presidential election on March 4, the die has already been cast.

What is happening in Russia today is part of a global phenomenon. Despite Putin's best efforts to isolate Russia and its post-Soviet near abroad, anti-authoritarian trends in nearby regions, like the Middle East, are infiltrating.

Russian voters, the establishment and intellectuals sense that Putinism has already lost. It is now only a matter of time before events make that defeat a political reality. And after Putin falls, the leaders of other authoritarian post-Soviet regimes — from Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko and Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev to Ukraine's would-be Putin, President Viktor Yanukovych — will not survive in power for long.

In fact, authoritarianism was already on the way out in the former Soviet Union, but the global economic crisis halted the process. Georgia was the first to oust its Communist apparatchiks. Ukraine followed, but — owing to internal discord, Kremlin pressure and the European Union's indifference — the Orange Revolution was unable to deliver on the promise of democracy. Now Yanukovych is trying to reverse the country's democratic gains, but he is finding it difficult, despite imprisoning many opposition leaders.

In Moldova, a real transition to democracy has been underway for some time. In Kazakhstan, too, rumblings against Nazarbayev's presidency for life are growing louder. Even the people of tiny South Ossetia, which the Kremlin annexed following its war with Georgia in 2008, are resisting the Putin regime's local puppets.

In Russia, mass disapproval of Putin's corrupt administration is rapidly turning into open contempt. What began just a few months ago as an attitude of protest has quickly become a social norm.

To stop the protests now is virtually impossible. If Putin unleashes his well-developed apparatus of coercion, he will have played his last remaining card. Any resort to brute force to suppress demonstrations would finalize the regime's loss of legitimacy.

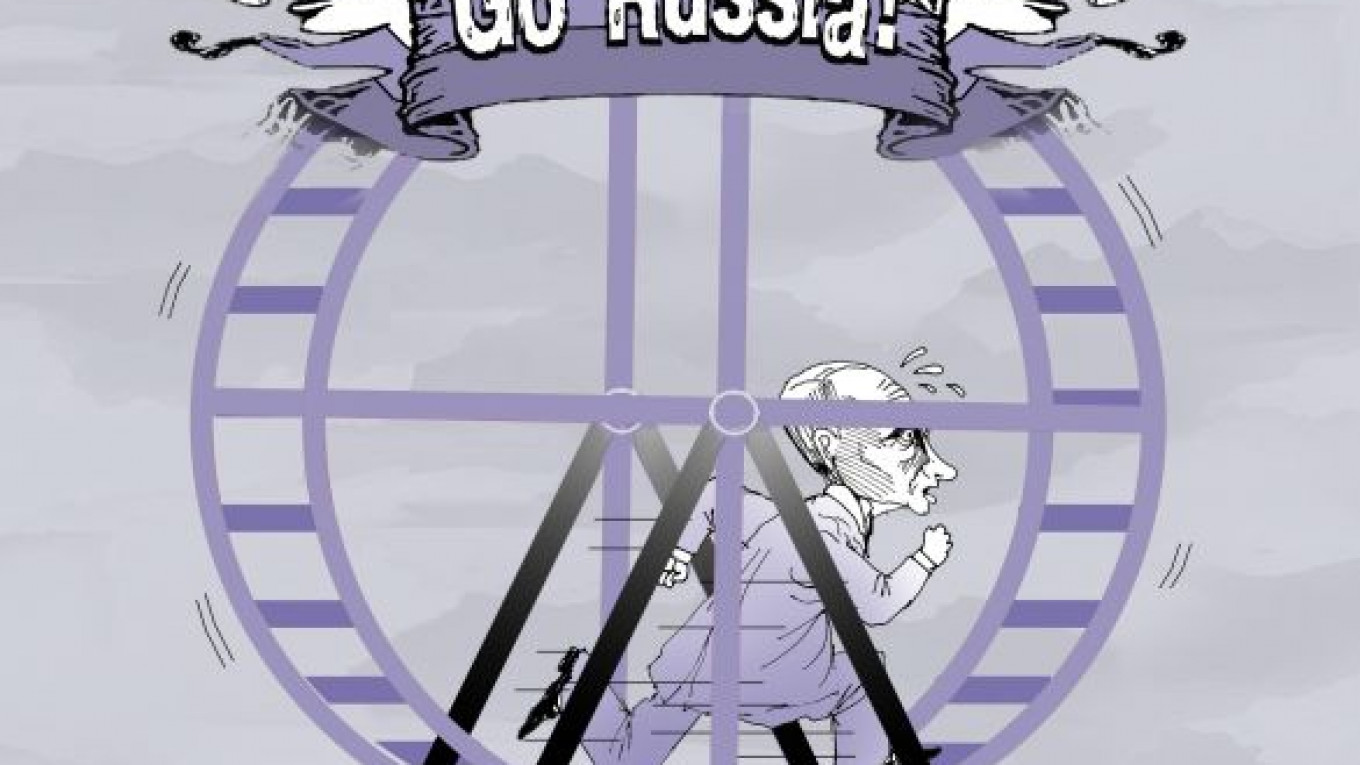

"We all understand this," one of the leading Kremlin ideologues recently confided to me, "but we can't get out. They will come for us at once. So we have to keep running like a squirrel in a cage. For how long? For as long as there is strength … "

Those who warn that the current government's collapse will be a risky leap into the unknown are correct. But they are mistaken to believe that preserving this government is safer. Russia must rid itself, once and for all, of Putinism's systemic corruption, lest the country be consumed by it.

Andrei Piontkovsky is a political analyst and member of the political counsel of the Solidarity movement. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.