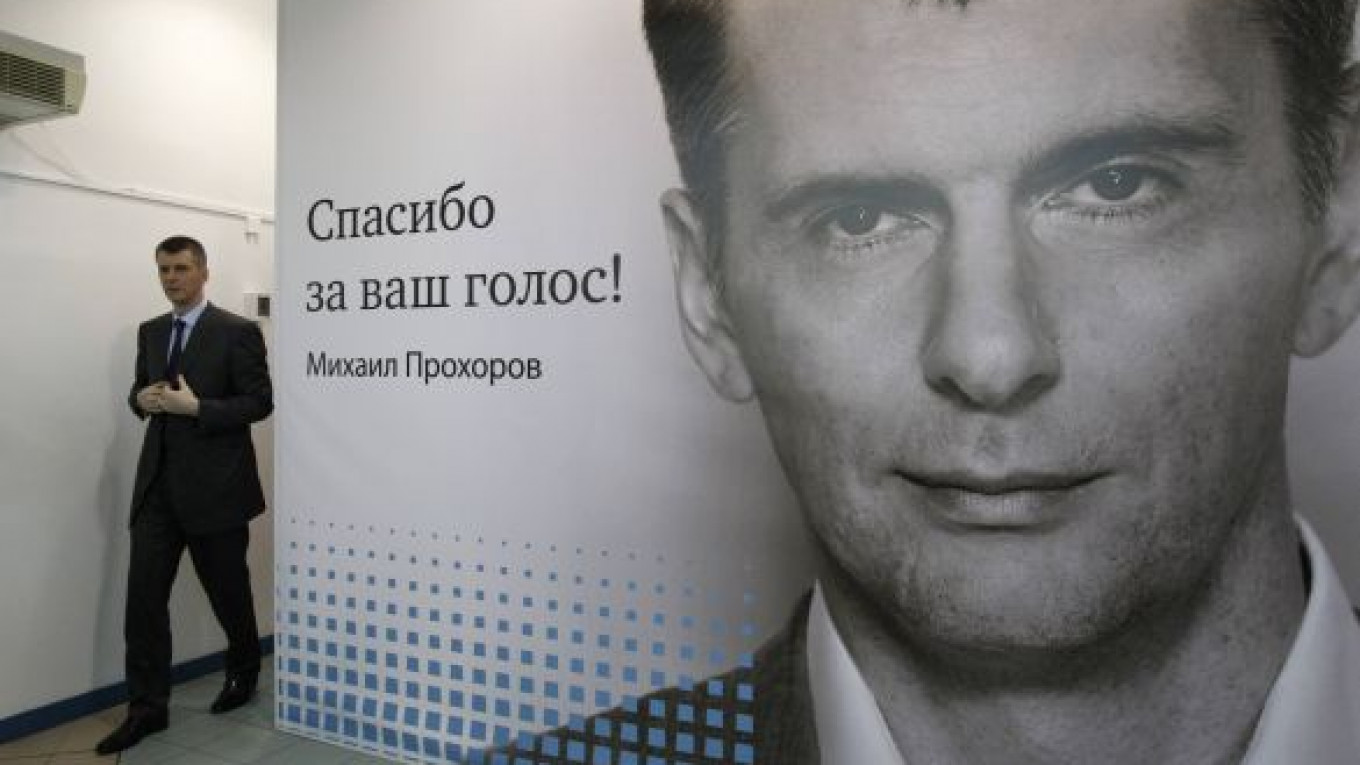

Mikhail Prokhorov, the billionaire challenging Vladimir Putin for the presidency in March, said Russia faced the danger of violent revolution if it did not break conservative resistance and move quickly to democracy.

Prokhorov, speaking in an interview, said Russians had shaken off a post-Soviet apathy and were now “just crazy about politics.”

He also denied accusations that he was a Kremlin tool, let into the race to split the opposition and lend democratic legitimacy to a vote that Putin seems almost certain to win.

Putin is seeking to return to the Kremlin and rule until at least 2018, but protests against alleged fraud in the Dec. 4 State Duma vote have exposed growing discontent with the system he has dominated for 12 years.

"What worked before does not work now. Look in the streets. People are not happy," Prokhorov, 46, said in the interview beneath the windowed dome that soars above his spacious office on a central Moscow boulevard close to the Kremlin.

"It is time to change," said Prokhorov, ranked by Forbes magazine as Russia's third-richest person, with an $18 billion metals-to-banking empire that includes the New Jersey Nets basketball team in the United States. "Stability at any price is no longer acceptable for Russians."

But Prokhorov made clear that he considers revolution equally unacceptable for a country with grim memories of a century of hardship, war and upheaval starting with the 1917 Revolution, instead calling for "very fast evolution."

"I am against any revolution because I know the history of Russia. Every time we have revolution, it was a very bloody period," he said, speaking in English.

Public political consciousness is on the rise after years of apathy. The Soviet mentality is fading as a generation of Russians who "don't know who Lenin was" grows up, he said. The country is finally ripe for change.

"We now have all the pieces in place to move very fast to being a real democracy," Prokhorov said.

But he suggested that there was a mounting battle in the ruling elite between liberals like himself and conservatives "ready to pay any price" to maintain the status quo. Russia, he said, could face a bloody revolution if opponents of reform prevail.

"If there are no changes in Russia, from day to day this risk will increase," Prokhorov said. "Because 15, 20 percent of the population, the most active ones living in the big cities, want to live in a democratic country."

Putin’s Puppet?

Prokhorov cast himself as the candidate for the upwardly mobile Russians who, wearing white ribbons or clutching white carnations in a symbol of protest, turned out in force last month for the biggest opposition rallies of Putin's rule.

"I think the era of 'managed democracy' is over," Prokhorov said. "I am in the habit of being very active, and I feel that it is time for politics."

He said that feeling was sweeping Russia, with debate over the future heard "in the kitchens, on the streets, in the elite — everywhere. Now we are just crazy about politics. … Just half a year ago, nobody had any interest in it."

He said he had proved he was his own man in September when he quit after a brief stint leading Right Cause, widely seen as a party controlled by the Kremlin to win liberal support.

Many opposition politicians, however, suspect Putin is using him to shunt middle-class anger into a safe channel in the presidential vote and to blunt opposition in its aftermath.

Prokhorov treads carefully around Putin.

He distanced himself from the prime minister by saying they had not met since April and that his "first act" if elected would be to free Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the jailed former oil tycoon whom Kremlin critics say was singled out for punishment by Putin during his 2000-08 presidency.

Prokhorov said he had no evidence that corruption, one of the country's biggest problems, reached to the top.

"I am a very practical man, and I like to have evidence."

New Duma Vote

He voiced one of the key demands aired at the street protests, calling for a new Duma vote after reforms to let more parties seek seats in the parliament and run in other elections.

If he wins the presidency, he said, he would dissolve the Duma elected Dec. 4 and hold a new vote in December 2012.

Prokhorov, who attended the biggest rally in Moscow, on Dec. 24, but did not address the crowd, offered measured praise for some of the street protest leaders.

But he echoed Putin's assessment that opposition leaders were disorganized, although in nicer terms than those employed by Putin, who likened them to chattering monkeys from Rudyard Kipling's “The Jungle Book.”

"They know how to bring people out onto the street, but then what? They have no position, no program," he said. A veteran of boardroom battles and business negotiations, he suggested his own brand of politics is more practical and productive.

Prokhorov made clear he intended to use the campaign to carve out a lasting, leading role in politics as a liberal leader.

"My goal is to win, but I have a long-term strategy and a short-term strategy," he said. "For the short-term strategy, I want to address all my ideas to the audience, and I want to receive maximum support from this presidential election. It will be a great platform to make a political party."

And while he is challenging Putin, he did not rule out becoming prime minister — if Putin shifts course and moves close enough to his vision of the future.

"If we have 80 percent or 90 percent the same program or we are on the same page, it's possible."

Putin and Medvedev have taken steps to appease protesters but rejected calls for a new parliamentary vote.

Putin Is ‘My Opponent’

Prokhorov said it was unclear whether Putin was capable of defusing growing discontent.

"It depends. He is smart, he is a very good politician, and as far as I know, a politician needs to react to what is going on in the world and what is going on in the country," he said.

"But he is my opponent for the time being, I have another view about what we need for Russia," Prokhorov said. "We will see who's right."

The very idea of Russia's third-richest man running for president is a sign the ground is shifting beneath Putin's feet.

Prokhorov and other oligarchs who built flashy fortunes on assets snapped up in the scandal-tainted, post-Soviet privatization drive were all but barred from politics as Putin tightened control after becoming president in 2000.

Khodorkovsky, who broke an unwritten compact with the Kremlin by funding opposition parties, was jailed in 2003 and is due to remain behind bars until late 2016, his Yukos oil empire long ago carved up and sold off into state hands.

Prokhorov's riches are rooted in Norilsk Nickel, now the world's largest nickel miner, which he and Vladimir Potanin bought at a knockdown price in the 1990s. Already a billionaire, he sold his stake to Potanin before the 2008 market crash. He kept his hand in an array of investments and was a stranger to politics until his brief stint as Right Cause leader last year.

Prokhorov dismissed the notion that his personal and business history made him vulnerable to control by the Kremlin.

"I have a great biography — it's very transparent," Prokhorov said. "I am a fighter and I am ready to fight, for my ideas and for my country.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.