The demise of the Soviet Union 20 years ago is usually seen as an event that profoundly changed the fate of the people who lived within the historical Russian Empire — from Estonia to Armenia to Turkmenistan. And, of course, it is a turning point in Russia's own history. The implications of the end of the Soviet Union, however, are far less often seen from a global perspective. Much of that is history, such as the end of Soviet meddling in the Horn of Africa or in Central America. Much is taken for granted and considered natural, such as the unity of Berlin, Germany and Western and Central Europe. There are things, however, that are less obvious and more relevant to this day.

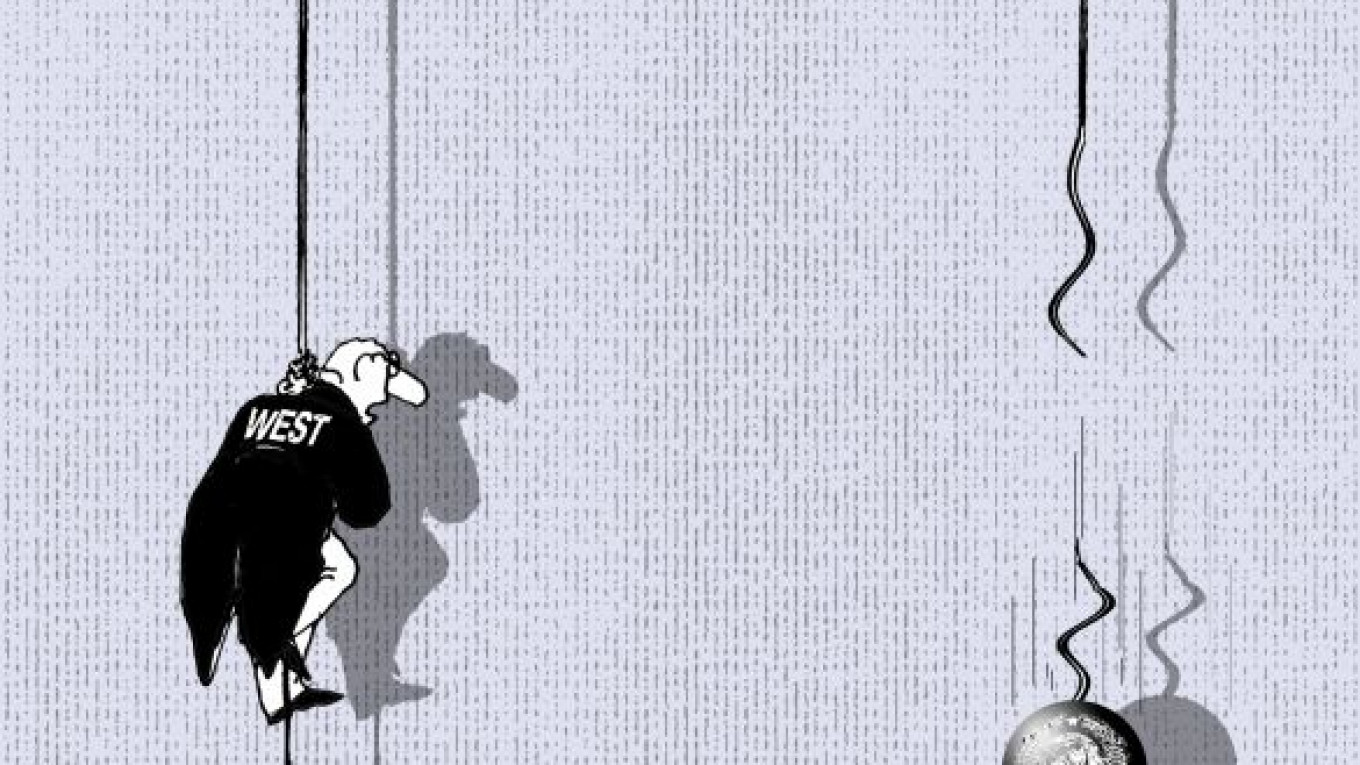

The abrupt withdrawal of the Soviet challenge to the Western world has not only allowed the tearing down of the hideous barriers that divided the European continent. It also presented the leaders of the then-Free World with a new challenge: leading an effort to create a Europe whole and free. Twenty years on, this business is only half-finished, with Europe as a whole enjoying only wary peace and having to put up with imperfect security. Those who pride themselves in winning the Cold War have done only a mediocre job organizing the peace that followed.

The removal of the U.S.-Soviet rivalry in the Middle East initially offered a prospect for a peace settlement between Israel and the Palestinians. This prospect, however, has proved elusive. Having come within inches of a solution that would have created a recognized Palestinian state and provided secure borders to Israel, the two sides have recoiled, and the mediators lost their drive. The U.S. forcible insertion into the region during the Gulf War in 1990-91 to liberate Kuwait — which was dramatically enhanced in the wake of 9/11 with the invasion and occupation of Iraq — made the Middle East more divided and more perilous.

The defeat of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan became a cause for celebration in the West and the Muslim world alike, but the forces that were unleashed by the anti-Soviet resistance were never properly understood, much less harnessed. Moreover, the operation of Western forces in Afghanistan, coming a dozen years after the Soviet withdrawal from the country, met with some of the same problems that bedeviled Moscow. The forthcoming departure of U.S. and allied troops from Afghanistan is threatening to create a major security problem for Central and South Asia.

The real issue is that the end of the Soviet Union and Soviet communism meant an end of hard peer-to-peer competition — in both geopolitics and ideology. Unconstrained power tends to corrupt those who wield it, while unopposed orthodoxy breeds narrow-mindedness and complacency. Those whose job is to lead and strategize follow the daily polls. The elites, who in the past used to rule, have concentrated on money-making. Those who make serious money have less time than ever for ethics. Those leaders, analysts and commentators who shape global opinions are often guided by the rules of political correctness.

To mourn the passing of the Soviet Union and its ideology is not the point. U.S. and European leaders should detect the faint scent of their own brand of Brezhnevism around their polities and amend their policies accordingly. For example, the United States is dangerously overextended abroad, and its political system at home has become too dysfunctional. Meanwhile, the European Union is in danger of losing the European project unless it rediscovers leadership and provides it with new legitimacy.

Cracking down on democracy and human rights in the name of efficiency is not the way. Authoritarianism is being challenged in Russia and will not survive forever in China either. Democracy needs a new model that is more applicable to the 21st century — and, above all, in the countries that gave birth to its 19th- and 20th-century versions. Democracies everywhere need to gain a global perspective. Those who claim leadership in the world need to gain a better understanding of it and become more global-friendly.

Citizenship, in the sense of civic duty and responsibility, needs to be fostered and promoted as the central pillar of politics, as well as in society at large. Protecting workers' outdated social benefits and the elite's excessive, newly acquired material gains must be held in check. In addition, leadership needs to acquire a broader and more secure base — for example, those who benefited from globalization and are looking for ways to spread those benefits even wider. Otherwise, past victories — like the one over communism 20 years ago — may pave the way to a defeat 20 years from now.

Dmitry Trenin is director of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.