Many observers have commented on how well-behaved, friendly and polite the police were during Saturday's opposition rally. The police did not blink when protestors chanted anti-Kremlin slogans or committed minor violations. Neither did they intentionally provoke demonstrators as they have done repeatedly in the past. Obviously, Kremlin officials decided on the eve of the rally to order troops not to use force. They decided that if they could not prevent the rally, the best approach would be to let the protesters blow off steam and dissipate on their own. After all, this is not the summer. The days are getting colder, and soon people will become preoccupied with New Year's celebrations and the accompanying extended national holiday.

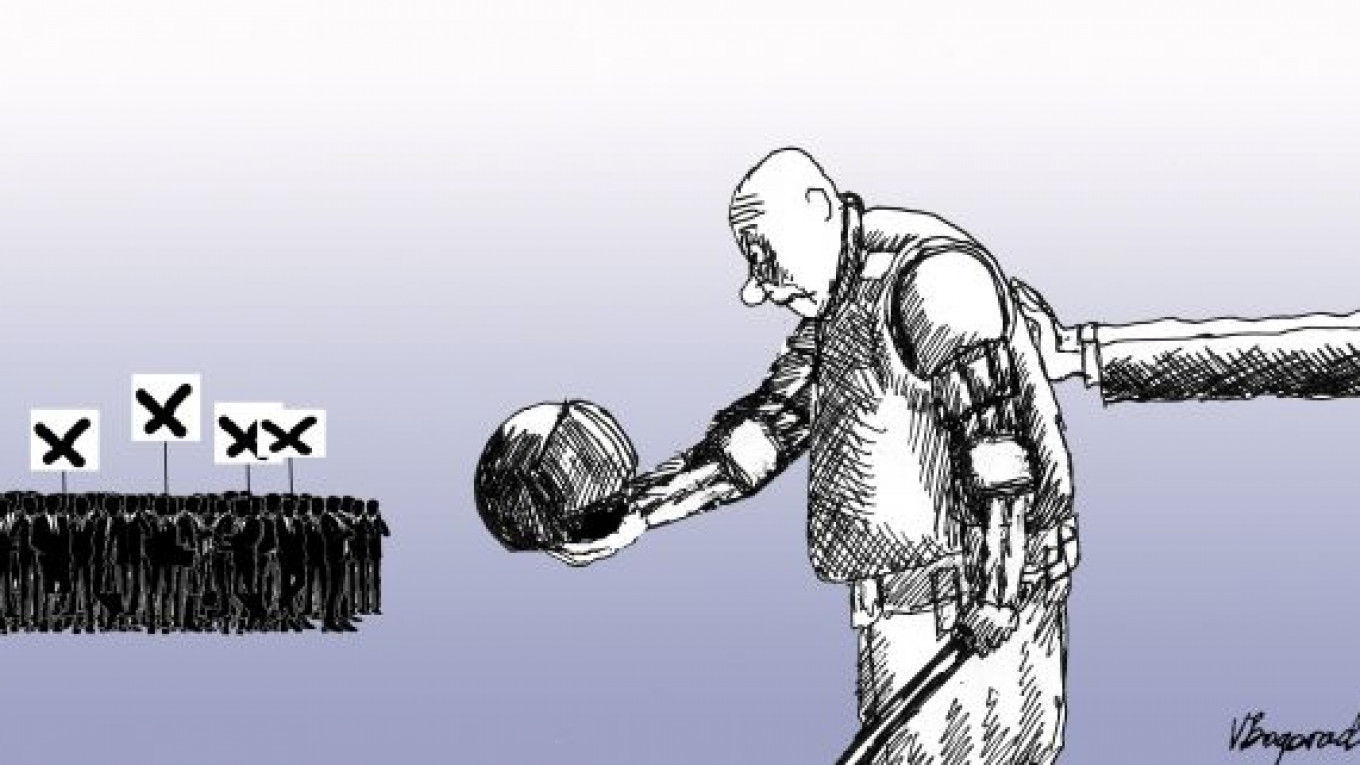

But any hopes for a return to the previous calm are unlikely to be bear out if the demonstrations continue and the number of participants increases. Frankly, there is little chance for a compromise between the authorities and the opposition. Prime Minister Vladimir Putin insists that the protests are organized by the U.S. State Department, and he really fears a "color revolution" in Russia. In this state of paranoia, orders might be given to the military and other security services to take actions that everyone would later regret.

Veteran special forces Lieutenant Colonel Anatoly Yermolin has issued an appeal to fellow officers that clearly describes the situation: "Through your helmet visor, you will see those who have gone off to serve their motherland. There will be the faces of people who look very much like your fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, good friends and neighbors." He then asks how a special forces commander should behave in a confrontation with fellow citizens. For him, the answer is simple: "to continue to serve your people even when politicians and their subordinate security ministers hand you an openly repressive task."

The military officer seems to have touched on the heart of the problem: People considered by Russia's leaders to be enemies are not necessarily enemies of the motherland. Furthermore, military personnel did not swear an oath to Putin or Central Elections Commission chief Vladimir Churov but to the very people whom they are sometimes ordered to beat.

Yermolin's recommendations boil down to two: First, orders from superiors should be as well-documented as possible. After all, senior commanders understand perfectly well that it is illegal to employ force against unarmed people and that leaders will never give them such orders in writing. Second, commanders should be prepared to get stabbed in the back by the politicians, who might provoke them into behaving like animals against protesters in order to shift blame away from themselves and onto the men wielding guns and batons.

Yermolin's advice is based on his experience in a sometimes prickly 20-year relationship between the authorities and the security services. After all, the lack of responsibility shown by the authorities has placed the security services in the difficult position of deciding whether they should carry out orders to put down popular demonstrations. This happened for the first time in 1991 during the attempted putsch by the so-called State Committee of the State of Emergency. On the evening of Aug. 19, Deputy Defense Minister Vladislav Achalov ordered airborne troops commander Pavel Grachev to arrest all of Russia's leaders. Grachev and his team agreed among themselves not to carry out the order, even knowing that they might face a tribunal.

Only Boris Yeltsin found the will and the charisma needed to use the armed forces for an internal political struggle — and he succeeded only once, in October 1993 when he had to personally go to the Defense Ministry and spend several hours persuading Grachev to use force against the Supreme Soviet. Clearly reluctant to comply, Defense Minister Grachev demanded a written order from Yeltsin — as he also had demanded of the State Committee of the State of Emergency in 1991. With the order in hand, the special forces opened heavy fire on people who had attacked the Ostankino television center. Then tanks of the Taman division fired directly at the White House. (The military and other security services must remember, however, that under the Criminal Code even a written order does not free them from responsibility for carrying out criminal orders.)

Why is it that the military refused to follow instructions in 1991 but agreed in 1993, two similar situations where there was no legitimate basis for orders? When are servicemen ready to beat their fellow citizens and even kill them, as happened in Tbilisi, Vilnius and Moscow in 1993? And when do they refuse?

Unfortunately, the reflex to unconditionally carry out orders can trump considerations of sympathy or humanity. That is precisely why the authorities are so careful to keep the military as part of the security-service structures. I think that the military would have been more willing to act in 1991 if the authorities had not already discredited themselves in their eyes. Commanders did not object to the forceful suppression of nationalist movements in the Baltic states and the South Caucasus. They disliked the way Russia's political leadership tried to pin responsibility for those actions on the military. Yeltsin, however, was unafraid to publicly assume full responsibility, so the military carried out his order.

Does Putin have enough strength of character to do the same? Putin has repeatedly shown that he considers it humiliating to submit to the demands of protesters who he believes are under the influence of outside forces. But he has always yielded to protests that he considered to be legitimate. Recall his reaction to pensioners' protests over the monetization of benefits or the protests over unpaid wages in Pikalyovo. Putin seems to consider social protests to be legal but political protests to be illegal. That might be because political protests have always been fairly small until recently. I suspect that an all-out struggle for demonstrators to support this or that cause will be waged in the media and the Internet in the coming weeks.

In any case, the best way to prevent the authorities from using force is to mobilize tens of thousands of people for protest rallies. To accomplish that, the opposition will have to agree on a common list of demands and, more important, a single presidential candidate. If to dream, why not dream big?

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.