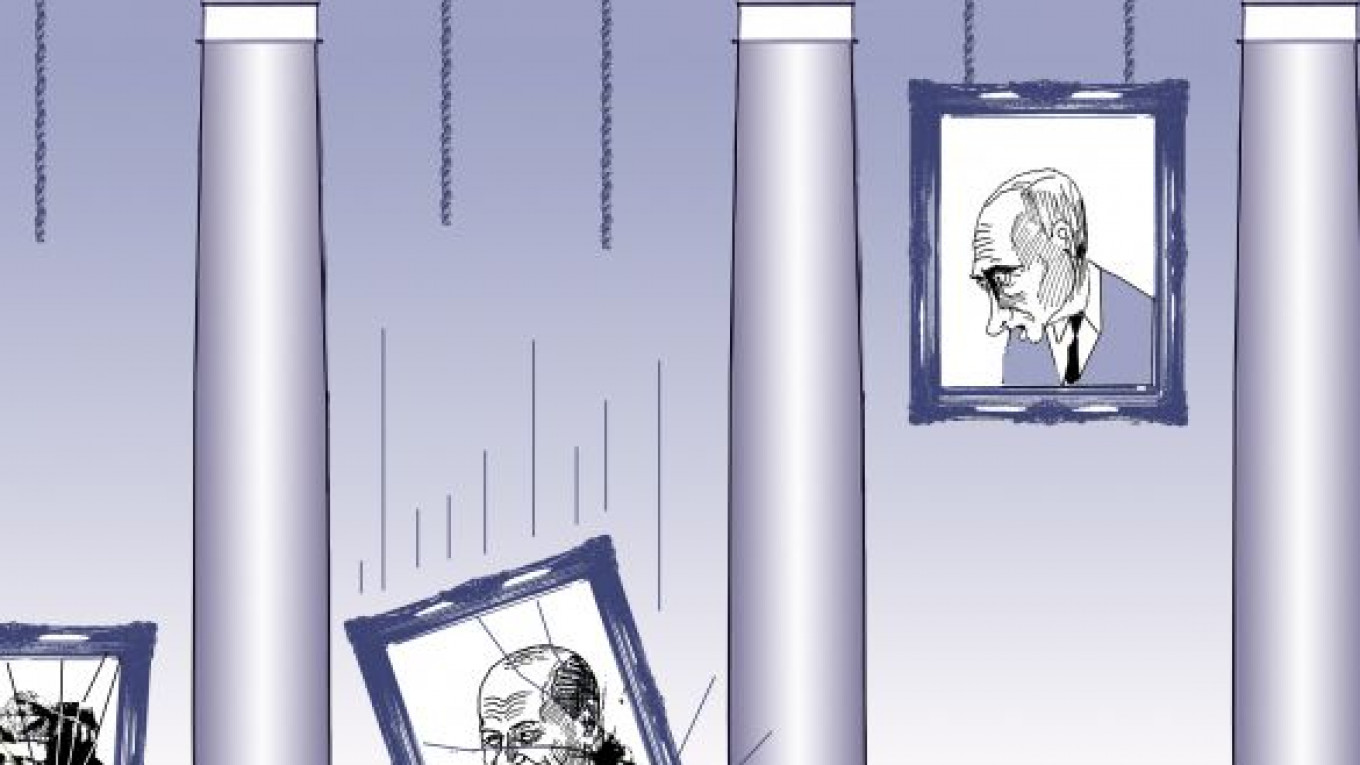

Silvio Berlusconi, whom Prime Minister Vladimir Putin called “one of the last Mohicans of European politics” during the Valdai Club meeting on Nov. 11, resigned hours later amid a financial crisis. He had served 17 years in Italian politics.

“I am convinced that Italy greatly benefited from his many years in power,” Putin said at Valdai, while praising Berlusconi for his “political stability.”

It is understandable why Putin held Berlusconi’s political skills in such high regard. The two share many of the same notions of state capitalism and “managed democracy.”

For one, as Alexander Stille argued in a Washington Post comment last week, Berlusconi increased the level of monopolization in key industries, trampling over elementary notions of conflict of interest.

Second, he helped his friends who were indicted on corruption charges get elected to parliament, where they enjoyed immunity from prosecution. Then, once in parliament, they passed legislation that benefited Berlusconi’s business interests.

Finally, Berlusconi, who sits atop his own private media empire, used his own version of “administrative resources” to control the content on the competing state television company, particularly to stifle critical reports of him.

According to Stille, under Berlusconi, “Italy plummeted by almost every international economic and social measure: from economic competitiveness and freedom to transparency and press freedom.”

Sound familiar?

The close Putin-Berlusconi bromance was a concern to Ronald Spogli, U.S. ambassador to Italy, who, according to published WikiLeaks cables, wrote that Berlusconi “admires Putin’s macho, decisive and authoritarian governing style, which the Italian PM believes matches his own.” Citing allegations from members of the opposition PD party, Spogli also wrote that Berlusconi and members of his elite may have benefited financially from the many energy deals between the two countries, including the giant $20 billion Gazprom-Eni South Stream pipeline project. (Berlusconi denied these charges.)

But the real question for Russia is what lessons, if any, will Putin learn from the Berlusconi era and its demise?

There is an old, established rule among actors to leave the stage at the peak of their careers so that they can leave a positive legacy. Berlusconi didn’t follow this rule. After he handed in his resignation, he was forced to sneak out of the presidential palace through a back exit to avoid angry crowds screaming “Buffoon!” and “Go home!”

In 2007, a year before his second presidential term ended, Putin, too, was at the height of his popularity. His ratings exceeded 80 percent. During this period, his most avid supporters led the “For Putin!” movement to try to convince Putin to change the Constitution and run for a third consecutive presidential term.

Others argued that Putin should step down in 2008 while he was still at the peak of his popularity. In this way, the argument went, Putin could leave Russia and history with a positive legacy: high economic growth, an increase in the standard of living for many Russians and a reversal — at least in part — of the chaos and lawlessness of the Boris Yeltsin era.

But Putin never really stepped down in 2008, as he himself divulged when he announced his presidential bid at the United Russia convention in September. The problem with Putin overstaying his welcome is that his stability-stagnation model of development is losing steam, and his approval ratings have dropped more than 20 points since 2007 to 61 percent, according to a Levada Center poll in November.

If this trend continues, and if Russia gets dragged down further in the global recession amid a drop in oil prices, Putin’s “Berlusconi moment” could very well come at his 18-year mark — in 2018, when his third presidential term ends.

But don’t expect Putin to exit stage left. First, Russia doesn’t have Italy’s checks and balances in parliament or civil society. Although far from perfect, they played a key role in convincing and pressuring Berlusconi to resign.

Second, Putin appears to be more out of touch with reality than Berlusconi, which happens when “absolute power corrupts absolutely.” (To make matters worse, Putin is surrounded by advisers and members of his inner circle who often feed him misleading information, seemingly driven by their own self-interest to remain in control for as long as possible.) Recall, for example, Putin’s statement in 2007, when, in answer to a question from a Der Spiegel reporter as to whether he is a “pure democrat,” he said only half-jokingly: “Of course, I am. … I am all alone — the only one of my kind in the whole world. … There is no one else [for me] to talk to since Mahatma Gandhi died.”

These delusions sound frighteningly similar to those of former Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, who also had no idea whatsoever when it was time to leave his post — or his country for that matter.

The real question is whether Putin will be smart enough to end his political career through the back exit a la Berlusconi. The other option — a bloody, violent Gadhafi-like denouement — is hardly an attractive one for Russia.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.