With the price of gold tripling over the last five years, some commentators have suggested that a bubble is forming in the gold market. Markets can become overheated, of course, but I believe that what we are seeing today is better explained as a return to a gold standard. Essentially, people want to know that their money is safe, especially with the extra liquidity and inflation that we now see in the global economy.

For Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States, this represents a considerable opportunity. Russia still has untapped gold reserves that could provide a stable and significant pillar of the economy for years to come. Gold miners were among the first Russian companies to issue initial public offerings, and sustained private and public investment will be the key to securing the industry’s future.

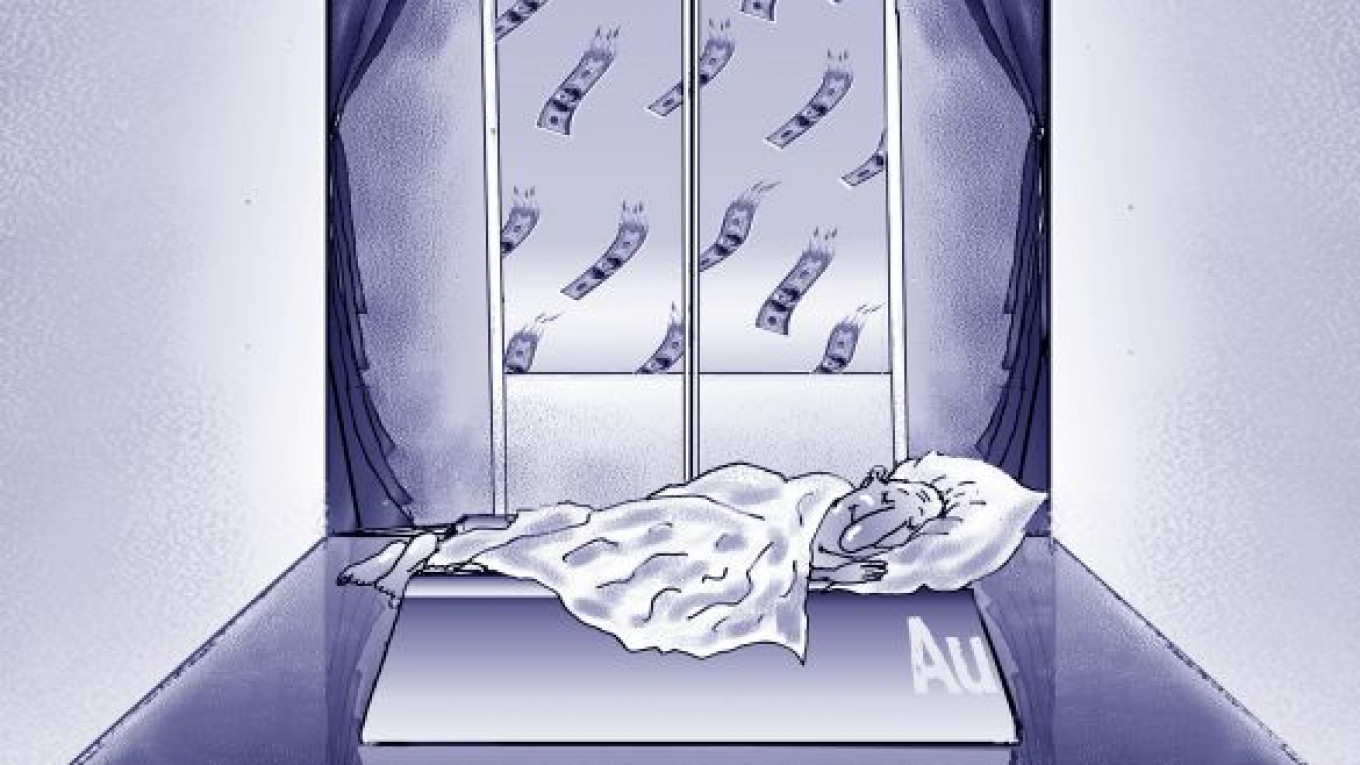

For private and even for institutional investors around the world, protecting their capital has never been more important. We can forget about the concept of stability as it was in our parents’ day, when one could reasonably expect healthy returns on bank deposits over a period of 10 to 15 years. If people today have any faith left in banks, it is in central and state-owned banks at best. Moreover, inflation, currency swings and shifts in purchasing power all erode the value of individual deposits.

Elsewhere, share prices have been rocked by volatility for more than three years, with benchmark indexes still below 2006 levels. Currencies — whether the dollar, British pound or euro — are no longer the inviolable state-backed beacons of stability they once were. Nor is sovereign debt necessarily a safe haven, with even the United States having its credit rating downgraded and experts talking about multiple defaults in the euro zone.

Debt issues in Europe are still being resolved, and there will be a lot more money printed and borrowed. These issues will take time to be resolved. European countries like Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain are concerned about the sustainability of their growth potential and the heavy exposure of their banking institutions to each other’s debt. We see more and more wealthy nationals from these countries shifting toward gold.

Gold, by contrast, has remained attractive to individual and institutional investors as a store of absolute value. In emerging markets, particularly where financial institutions are underdeveloped, people are buying physical gold — and at above-market prices. Russia is no exception as the world’s sixth-largest consumer of gold last year.

Central banks also store significant amounts of the metal in their reserves, with those from emerging economies among the biggest buyers. Again, Russia is no exception. The Central Bank has increased its gold stocks by about $8 billion this year, despite some limited sell-off to defend the ruble. By contrast, mature economies are selling gold to support their own liquidity.

Yet even as demand has increased, supplies are dwindling. There are few gold fields left with reserves of 30 million to 40 million ounces. Even major mining companies are looking closely at deposits of less than 5 million ounces. Some underexplored areas remain — including in the Sakha republic and Siberia — but nobody expects that giant deposits will be discovered.

Nor are production costs getting any cheaper, despite the introduction of more modern mining methods and technology. Artisanal mining, the main technique used in the Soviet Union, is declining, as deposits of placer gold dwindle. Industrial mining, which has replaced it, is more expensive. Since input costs such as fuel, equipment and chemicals are rising, getting the metal out of the ground is becoming more difficult technically, and environmental requirements are becoming stricter.

Not even the bravest economist at present would try to forecast the outlook for various economies over the next 10 or 15 years. But current trends clearly illustrate that economic influence is shifting toward consumer countries and away from producers. In 20 years, consumer nations — those with large populations, a middle class and a young and educated population — will wield much greater influence than their producer counterparts.

This presents natural resource-based economies such as Russia with something of a balancing act. Russia has for some years declared its intention to rebalance the economy away from its traditional energy bias in favor of innovation, financial services and high-tech sectors such as nanotechnology. But the country’s mineral wealth still has much to offer. Some metals, such as lead, are no longer as important as they were, but others, such as gold and copper, are crucial to the global economy and Russia as well.

Production requires investment and supporting infrastructure to mine the ore, process it and deliver finished products to consumers, while meeting sustainability and social commitments. Private companies, both Russian and foreign, have already demonstrated that they have the appetite to make Russia’s gold-mining industry a success. This, combined with the state’s efforts to create a favorable investment environment, should lead to the continued successful development and growing importance of the Russian gold industry for years to come.

Siman Povarenkin, a global investor in metals, mining and medical technology in Asia, Europe and Latin America, is the main shareholder in GeoProMining.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.