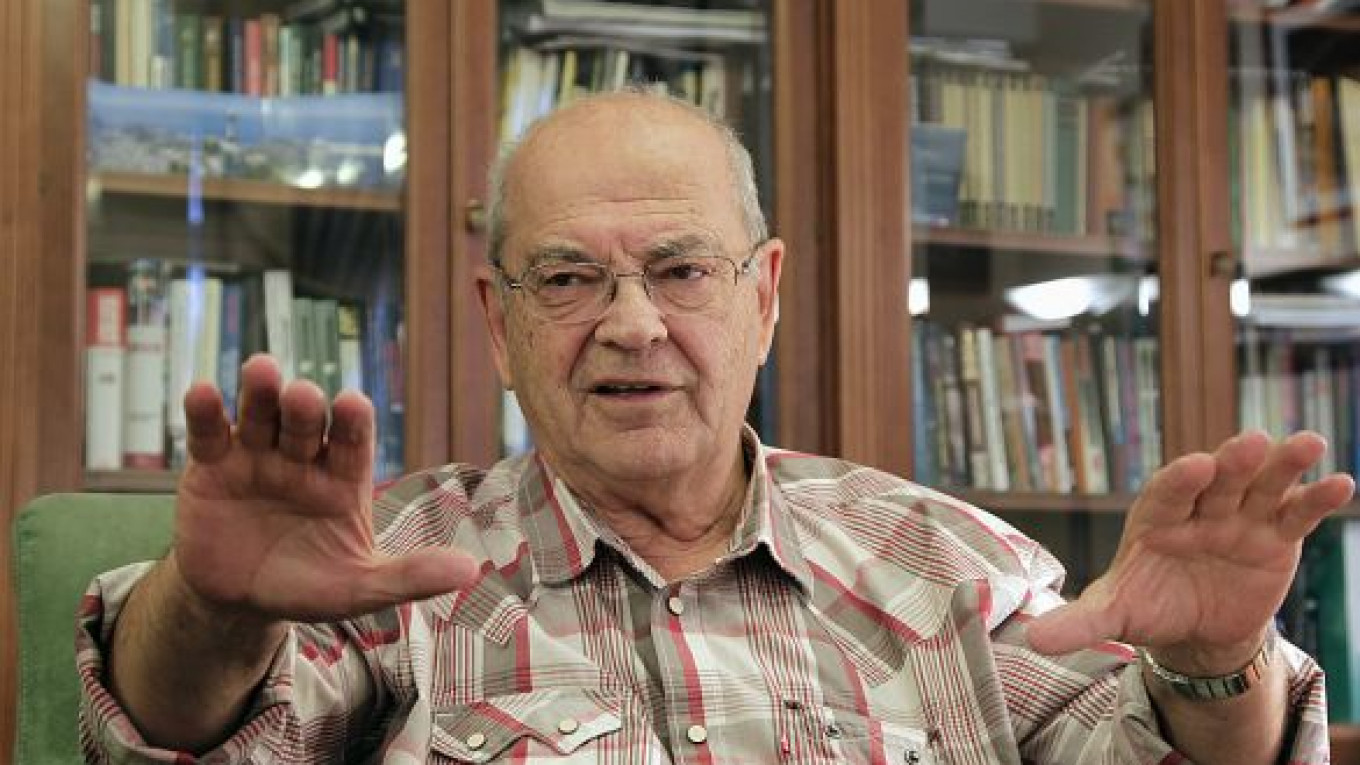

You might think the energetic elderly gentleman, dressed in jeans and a plaid shirt, gesticulating to prove his point, was a venerated professor in animated discussion with one of his students — and not the godfather of Russia's mobile telephone market.

At 78, Dmitry Zimin is not your typical businessman. His success in creating VimpelCom , and growing it into the country's first corporation to go public on the New York Stock Exchange, overshadows his own personal transformation.

As a senior engineer at a leading "post office box" — Soviet speak for secret institutes working on military-industrial projects — he helped create the U.S.S.R.'s missile defense shield during the Cold War. That same inquisitive scientific mind helped him see around the corner, embrace the fashionable late-Soviet concept of defense conversion and become a pioneer of Russian capitalism. He credits his success to finding a great foreign partner and early on embracing Western business values.

Zimin's memory is sharp. He easily recalls the names of dozens of people and recites lines of poetry by heart to prove his point. He speaks nostalgically about his early days as an engineer and confesses that at night he sometimes has dreams about the radar station he developed as part of the defense of the motherland.

Passion is a recurring theme for Zimin and explains how he thrived through the whole cycle of business — from founding a company in the wild '90s to his retirement a few years ago, when he saw VimpelCom become embroiled in conflicts over licenses, tax bills and radio frequency allocations, which he attributes in part to the meddling of former Telecommunications Minister Leonid Reiman.

But Zimin is thankful that the situation gave him an impetus to retire. In discussing contemporary Russian politics, he states firmly that any leadership that holds on to power too long is destined to degrade.

Zimin's cozy office wall is covered with pictures of himself with company executives, as well as political and business leaders — including jailed Yukos tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Zimin was among the first businessmen to speak out against Khodorkovsky's arrest. He doesn't hide his liberal political views and speaks favorably about opposition leaders.

The man who started his career developing the country's defense against possible American attack is now more concerned about the growing global population. "We have 7 billion people, and out of those 7 billion, only 1 billion live in normal conditions. The pressure of those 6 billion is a much more serious challenge than some kind of American threat," he said.

Now Zimin is mostly engaged in philanthropic work through his Dynasty Foundation, the first family charitable foundation in modern Russia. Among other activities, the organization supports 20 different projects for young math and physics teachers.

Dmitry Zimin

Education

1957 — Graduates from the radio engineering school of the Moscow Aviation Institute.

1963 — Ph.D.

1984 — Doctorate in technical science.

Work Experience

1962 — Joins the Mints radio technical institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow, a part of the Vimpel military-industrial enterprise. Started as the head of the lab, working his way up to deputy chief designer in charge of construction of anti-ballistic missile radar installation.

1990 — While working at Vimpel, joins the cooperative Impuls design bureau as general director; the company produced radio equipment for civil use.

1992 — With his U.S. partners, starts the VimpelCom cellular network company and becomes company president.

1996 — VimpelCom holds first Russian IPO on NYSE.

2001 — Retires from the company and becomes chairman emeretus; Dynasty Foundation created.

Favorite books: Likes books by famous physicists and mathematicians; nonfiction books on politics and economics.

Favorite restaurant: Pushkin

Though it seems a natural choice, Zimin has a philosophical reason for focusing his support on the sciences. "I learned that pursuing science demands honesty and a critical approach — even to authority."

Q: VimpelCom is recognized as a symbol of success. How was that achieved?

A: The project to launch a cellular phone network in Russia was unique, since it is perhaps the only major project [of that time] done without financial support of the state. VimpelCom came into existence thanks to the fact that our partners gave us unsecured credit lines: We had no financing.

Our first supplier was an American businessman named Augie Fabela. His company, Plexsys, supplied the equipment on which we based the first cellular network.

Then we got another unsecured credit, this time from Ericsson. They trusted us — saw how our eyes were burning with passion for the project — and they believed in Russia.

The second unique aspect of the project was that it facilitated implementing in Russia a Western-style company with a Western management culture. It was a revolution in labor productivity.

I was 60 at that time, but I had never experienced such a passion, and was lucky to get in on a business when it was being built from nothing. Those first 10 years were the happiest of my life.

I remember we had a corporate celebration to mark the 10,000th subscriber. We held the event on a boat. One of our oldest employees came up to me with a glass of cognac and said, "Dmitry Borisovich, this is the first company I've worked in where I don't steal—"

I've never gotten a more flattering compliment.

In general, the project … was successful for several reasons: It was a greenfield project — nothing similar had existed. Telecommunication in general was considered something secondary — not strategic, like a toy for rich people — so the authorities didn't interfere at the time. And, finally, we were able to develop a close business partnership with the West.

Q: How were you able to start business with a Western partner, while still working for the Soviet defense industry?

A: It was a pure accident. At Vimpel, the Soviet defense industry giant, it was almost impossible to imagine seeing foreigners walking down our top-secret corridors.

Vimpel employed 100,000 workers and had a huge number of institutes, including Mints Radio-Technical Institute where I was working. The late Vasily Bakhar was overseeing conversion [of military activities to civilian ones] in the institute and turned out to be the only man in the whole place who spoke English.

I had already started a small cooperative company and had plans to invite foreign partners, so he invited me to a meeting with Fabela, whose family company produced cellular equipment and was trying to find a market for it in the U.S.S.R.

The meeting resulted in a cooperation agreement between Vimpel and Fabela to start a joint venture to produce cellular equipment.

From our side, we were supposed to obtain the permit from the authorities to create a commercially viable network capable of serving 600 subscribers. Shortly thereafter, Vimpel managers were invited to visit the United States.

When Fabela was sent the list of proposed delegates for approval, he stressed that he wanted to see "the bald gentleman who gesticulated a lot during the meeting," so I was able to make my first visit to the United States.

Q: What are your recollections about the trip?

A: There was an interesting episode. It was a delegation of one of the largest Soviet defense industry companies, but no one had any money. One day, Fabela's father, who was also with Plexsys, asked us to accept a gift: He gave everyone an envelope with 50 dollars cash. Several years later, after we had taken VimpelCom public, Fabela senior came to Moscow. We got together at a restaurant, and I told him that I want to return the debt. I gave him an envelope containing about $5,000. He didn't accept it, but shed some tears — it was a touching scene.

Q: You came to business as a mature man with an existing set of values. Was it hard for you to operate in a situation when many businessmen and officials broke ethical standards?

A: I have experienced this nightmare — facing a government official who was operating on the market in violation of all rules of morality and fairness. It was unacceptable and unfair pressure from the government's industry regulator — which turned out not to be a regulator, but a competitor.

However, I have a certain feeling of gratitude toward this man, since he helped me decide to retire.

But, by and large, we should talk not about the sense of fair play of that regulator, but we should blame the one who gave him his position.

If you leave the goat to guard the vegetable garden, he isn't to blame for the consequences. That's exactly what they did here, and the consequences were serious.

Q: Has the telecommunication market become more civilized?

A: I'm not fully tuned in to today's situation, but I think that with such giants operating globally and in Russia, the games played by officials have changed. The minor fraud that took place before is probably less possible today. But, overall, the situation in Russia, in terms of the role the government plays as a regulator, has gotten worse.

Q: Has your scientific background helped you in business?

A: Probably. But I would like to point out that I was not alone.

Fabela did a lot to enlighten me — taking the company public, introducing corporate governance, and so forth. For example, it was an amazing discovery for me to learn that long-term financing is based on pension funds — that the savings of pensioners is a driver of the global economy! Can you imagine the pathetic role of pensioners in the U.S.S.R. — that their savings could play a key role in international finance?

Take the concept of "conflict of interest" — I had never heard such a phrase! At first I didn't understand what the issue was when our lawyer, Melissa Schwarz, criticized me because I gave a contract to service my corporate vehicle to my son's company. I wound up tearing up the contract.

Fabela also introduced me to the idea of hiring outside consultants. As a Soviet-educated man, the idea of paying an outside organization to propose solutions to our problems was simply wild.

Q: Why was conversion of defense companies to civilian manufacturing not successful in Russia?

A: I had the impression that Russian state companies considered conversion a last priority and an entirely unmanageable task.

We were a country where people were waiting in line to get a home phone, and look what we have now! I am sure that if [the creation of mobile telephony] had been attempted by a leading Soviet defense company using state funds, we would still not have a cellular network now. I say that as a person who worked for 30 years at one of the leading companies in the military-industrial complex.

VimpelCom was an entirely new enterprise — to convert an old enterprise would have been an impossible task for me.

I remember the fundamental inefficiency and idiocy of the Soviet defense industry. A top-secret regime from top to bottom and a system where the buyer and producer were in the same boat but it was necessary to coordinate each and every bolt with him.

The manufacturing culture was ineffective and populated by a huge quantity of unnecessary people — but still, it was my life and youth.

Q: How do you regard Defense Ministry plans to purchase foreign-made weaponry?

A: It is one of the few correct things being done by the authorities. My experience at VimpelCom has shown it is impossible to speak about any business in a non-competitive environment. The enterprises of the military-industrial complex work in a non-competitive environment, and much of their production is a waste of money. As far as I know, in the West there are no manufacturers focused exclusively on defense orders from the government. Working just for state orders is a form of degradation.

It's not an accident that they say the level of corruption and kickbacks in the military-industrial complex is one of the highest.

Q: Your family is the first in the post-Soviet era to organize a charity foundation. What made you do this?

A: The unique thing is that, among business leaders, I happen to be the oldest. When the others will be as old as I am, they will do the same. There are different types of charity, which depend on the age and status of the sponsor. It's odd to imagine oneself at the age of 20 being a philanthropist. For successful philanthropists, their charity is connected to their business. If they support sick children in their city, that is very good.

Q: As a head of a charity organization that supports scientists, what do you think of the Skolkovo Foundation?

A: Skolkovo is probably useful. But our basic problem is not the creation of new scientific centers but creating the conditions for people like Steve Jobs to appear. We don't have those conditions now.

The poet Dmitry Bykov explained it in a recent poem devoted to Jobs: "The moral conditions in the country are such that such figure is unlikely to emerge."

Creation of such conditions demands competitive conditions in science, politics and business. Deceit and unscrupulousness in any area of life affects society as a whole — and it makes some people feel disgusted to be here.

Q: Did you have any hope that Medvedev would run for a second term as president?

A: Yes, I did. I don't expect anything good from Putin's return. And it is not Putin as a person that is important. The extended presence of any individual and limited group of people in power leads to negative consequences both for the object of rule and for the subject. To a certain extent, I even had regrets about Luzhkov. It was a pity that he wasn't smart enough to retire — he would have departed with honor. In my opinion, Putin would have been the greatest contemporary politician if he had decided not to stay for another term. I retired, and I know how hard it is, but necessary. I know that if I had remained, it would have been bad for the company, and in the end, I would have been kicked out.

Q: Who are your role models, in life and in business?

A: My personal destiny was influenced by my schoolteachers — my physics teacher Sergei Alexeyev, who attracted me to ham radio, and my math teacher Ivan Morozkin, who taught the great mathematician Vladimir Arnold. In my choice to support fundamental science [with our foundation], I was influenced by knowledge of the greatest scientists of the modern era, from whom I learned that pursuing science demands honesty and a critical approach — even to authority.

There is a book, "Science and Morals," where I came across a saying by a Russian physicist: "While choosing your path in life, choose not the shortest way, but the way by which you will receive the greatest wealth of impressions."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.