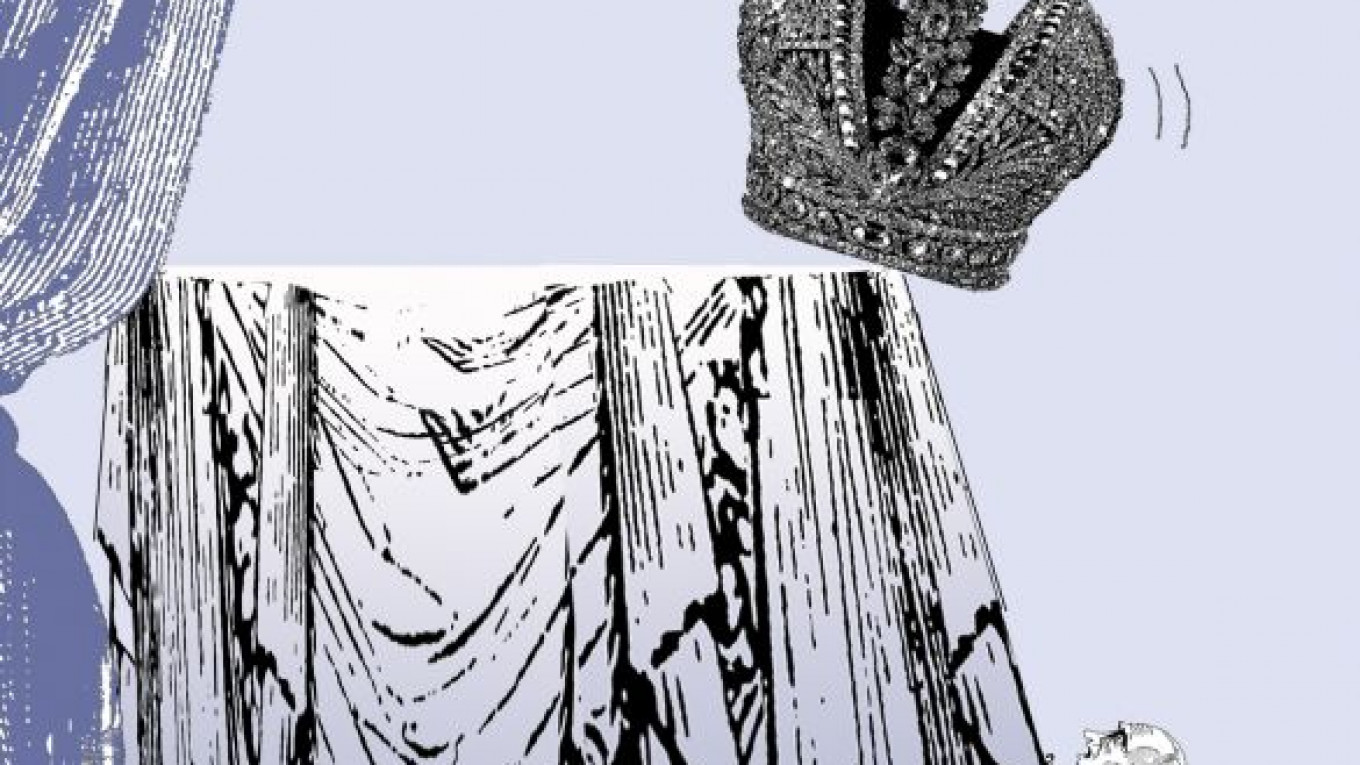

The only vote that matters in Russia’s 2012 presidential election is now in, and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has cast it for himself. He will be returning as the country’s president next year.

When the news broke — together with the lesser news that the incumbent, Dmitry Medvedev, will step down to become Putin’s prime minister — I wanted to scream, “I told you so!”

I have always been puzzled by the naivety of analysts, in Russia and abroad, who believed that Putin would never be so bold as to make a mockery of the country’s electoral system by reclaiming the presidency. But contempt for democracy has been Putin’s stock-in-trade ever since he arrived at the Kremlin from St. Petersburg two decades ago.

Anyone who thought that things would be different was either delusional or ignorant of Russia. Putin cannot help himself, just as he could not help himself in 2004. Then, as a very popular leader who restored Russia’s self-respect as a global power amid high energy prices, he would have won hands down. Yet he manipulated those elections nonetheless. In the KGB tradition, people are simply too unpredictable to be left uncontrolled.

If many analysts were blithely unaware of the certainty of Putin’s 2012 return, the Russian public certainly was not. Culture never lies about politics. When Putin installed Medvedev as president in 2008, a joke made the rounds. It is 2025, and Putin and Medvedev, now elderly, are sitting in a restaurant. “Whose turn is it to pay?” Putin asks. “Mine,” replies Medvedev. “Remember, I just replaced you as president again.”

Mikhail Kasyanov, a prime minister under Putin and now co-leader of the opposition People’s Freedom Party, insisted that “nobody knew” about the swap. If he believes that, he is fooling only himself.

The sad truth is that in Russia history does indeed repeat itself — but in a twist on Karl Marx’s dictum, as tragedy and farce at once. Power in Russia is a product of inertia and personal willfulness, and a generally apathetic public has traditionally surrendered to the country’s paradox of tyranny: a weak state believes that it can function as a strong state by depriving citizens of basic liberties and the ability to make their own decisions.

In such a state, initiative — especially political initiative — is worse than futile; it is a crime, as the case of former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky has demonstrated. The only freedom Russians have left is to devise bitter jokes that tap the country’s rich historical stores of political pathology. If they could export them, they would be as rich as Germans.

In the absence of rule of law and functioning state services, we Russians generally perceive ourselves as subordinate to the state rather than as citizens acting out our lives in a functioning, vibrant and independent civil society. This de facto surrender creates a fertile environment for despotism.

For many Russians, if not most, the authority figure embodies the powers that control everything that matters in life. Russians support him, regardless of the policies that he implements, because there is no possibility of doing otherwise. This partly explains enduring popular devotion to rulers like Josef Stalin.

The question today is not about the outcome of next year’s presidential election; that has already been determined. With the presidential term now extended to six years, we can expect an encore lasting up to 12 years — longer than Putin’s original performance.

But now the delusional and ignorant want to believe that Putin will become a reformer this time around. I remember a similar analysis in 2000, when experts tried to equate Putin’s KGB background with U.S. President George H.W. Bush’s years as director of the CIA. Putin, they argued, is not your typical security tough guy; he is an enlightened technocrat. But the only technique that Putin appeared to have absorbed from his earlier career as a spy in East Germany was that of social control. That remains true today.

Still, looking beyond the 2012 election might be worthwhile, because the economic, political and social contexts have changed since 2004, when Putin re-elected himself, and since 2008, when he pretended to be a democrat by promoting Medvedev. Today, Russia’s rulers have never looked more arbitrary and illegitimate. After 12 years in power, and grasping for 12 more, Putin can no longer sustain the pretense of adhering to democracy and promoting modernization.

During the last few years, popular support for Putin has weakened considerably, largely due to a stagnating, commodities-based economy. So manipulating presidential powers might not prove as simple as before. Indeed, Russia’s elites know that things are going wrong and are voting the only way they can — with their feet and by bank transfer, moving their families and wealth out of the country.

History also teaches us that, despite their inertia, Russians are capable of turning on their government, as they did in 1917 and 1991. So when resettling comfortably in the Kremlin in 2012, Putin should take a moment to reread Alexander Pushkin’s “The Captain’s Daughter,” a novella about the bloody Cossack-led rebellion against Catherine the Great with its oft-quoted but nonetheless important and relevant message for today’s regime: “God save us from a Russian revolt, senseless and merciless.”

Nina Khrushcheva, author of Imagining Nabokov: Russia Between Art and Politics, teaches international affairs at The New School and is a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute in New York. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.