Kremlin politics is so opaque that it functions like a sort of personality test. Optimists glean just enough hope to justify their wishful thinking, while pessimists find hints of the most monstrous conspiracy theories. What’s visible on the surface seems much too obvious to be true.

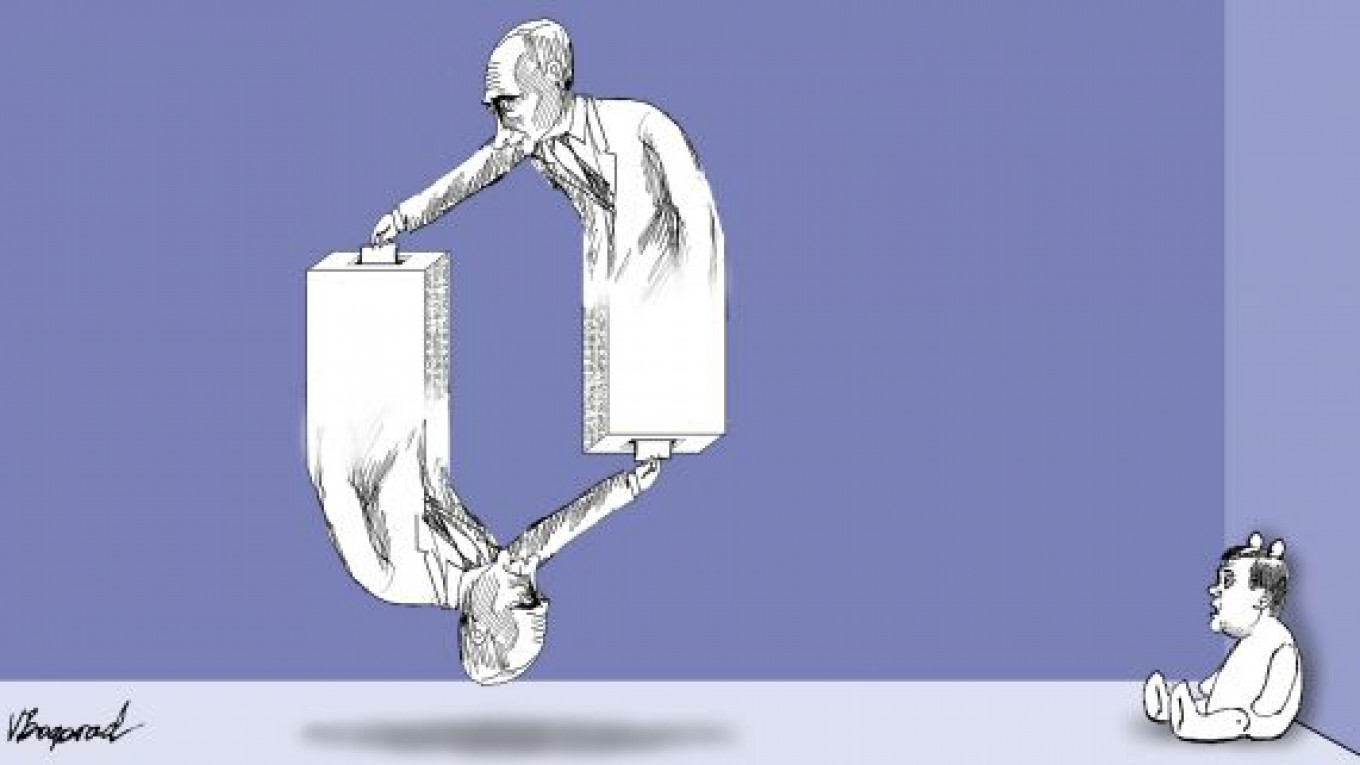

Since the weekend, the world knows that Prime Minister Vladimir Putin always planned to return to the presidency and that President Dmitry Medvedev really was only keeping the seat warm for him. The scenario is brazen in its simplicity: Russia’s two most powerful men nominating each other for their respective positions before 11,000 cheering supporters. Putin openly admitted that the arrangement had been agreed on “years ago,” as if that lent it any more legitimacy.

Cynics were not disappointed. But for optimists, the announcement was a rude awakening. As long as Medvedev participated in the “tandem,” there was hope for a generational break. Now it’s clear that Medvedev won’t run for a second term and finally start his modernization program.

It turns out his entire presidency was an elaborate feint. Who recalls the “national projects” Medvedev headed as first deputy prime minister during Putin’s presidency? Who will remember the Russian Silicon Valley and the police reform in a year from now?

Medvedev looked relieved Saturday as he passed the mantle back to his mentor. If anything, Putin’s declared intention to run for president gives some clarity, if not honesty, to Russia’s political process. It ends pompous, empty speeches at international forums and news conferences about nothing in particular.

Medvedev made the rashest move of his presidency on Monday when he fired Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin for publicly disagreeing with him. Dismissing the Cabinet’s most competent minister as Russia’s economy teeters on the brink of a new crisis is the first decision by Medvedev that carries real, lasting consequences for the country.

Everybody takes for granted that Putin will win the March vote in a landslide. Even though the election has turned into a farce, it is crucial for validating Putin’s return to the Kremlin. Ultimately, he bases his claim to power on his still-high popularity and a strict abidance to the letter of the law. How much he has honored the spirit of the law is another question.

While the Constitution only imposes a limit of two consecutive presidential terms, it is doubtful that its authors, including former President Boris Yeltsin, wanted to give former presidents the ability to make secret agreements with their successors to come back for a third — or even fourth — term. What’s more, the Constitution originally foresaw a presidential term of four years — until Medvedev changed it to six, essentially adding a third term to a two-term presidency.

The purpose of term limits is to prevent one person from monopolizing power, no matter how popular he is. A year ago, Putin referred to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four consecutive elections in an oblique justification of his own ambitions. Yet it was exactly FDR’s electoral success that spurred the introduction of a total limit of two terms for U.S. presidents.

Putin no longer has to worry about constitutional restrictions or sharing power until 2024. He now can focus on shaping his historical legacy, and in that sense he is only halfway through his rule. The accomplishments or failures for which history will remember him most may well still lie ahead of us.

It’s often not clear whether long-serving, powerful leaders succumb more to cynicism or self-delusion in the end. Their greatest vulnerability is that they lose touch with the problems of ordinary citizens at staged events and among fawning ministers.

Perhaps Putin really did imagine that he was speaking at a genuine party convention on Saturday. It gets dangerous when he starts falling for his own tricks.

Lucian Kim is a U.S. journalist who started his career in Berlin and was based Moscow for the past eight years. He is writing a book on Putin’s Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.