Twenty-five years ago, at a summit in Reykjavik, Iceland, U.S. President Ronald Reagan stunned the world and his Soviet counterpart, Mikhail Gorbachev, by proposing the comprehensive elimination of all nuclear weapons. Unfortunately, the skepticism of the U.S. defense establishment, together with Reagan’s adamant refusal to abandon his Strategic Defense Initiative, nipped this bold move in the bud.

That was a tragic missed opportunity that might have had truly global meaning. Although U.S. and Russian stockpiles still account for more than 90 percent of the world’s nuclear warheads, U.S. President Barack Obama’s disarmament goal, Global Zero, is proving far harder to accomplish now, given how much the world has changed since the Cold War’s end.

Not only has the number of nuclear states increased, but the “nuclear renaissance” — the revival of nuclear power owing to rising oil prices and environmental concerns — has put nuclear technologies into growing use. This revival holds important implications for nuclear proliferation.

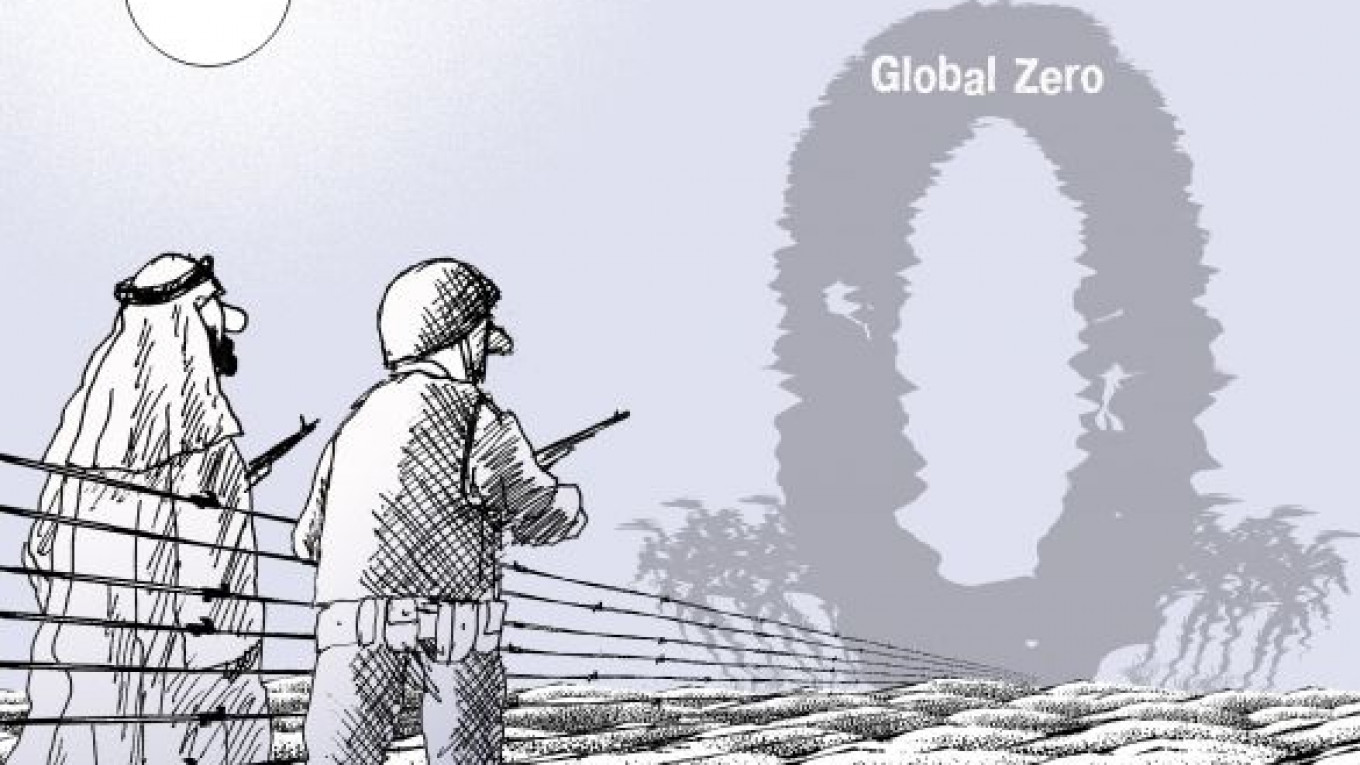

More important, China, India, Pakistan, Iran and Israel might not be particularly impressed by Russian and U.S. assumptions that they can meet their defense needs with far smaller nuclear arsenals. Nuclear disarmament must therefore focus not only the total elimination of stockpiles by the major powers, but also on regional powers’ concerns. Global Zero must go hand in hand with a robust strategy of conflict resolution and confidence building in trouble spots such as Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

All the nuclear weapon-free zones that were created in the last decades — for example, by the Tlatelolco Treaty for Latin America or the Treaty of Rarotonga for the South Pacific — were made possible by understandings that were reached freely by regional powers in an atmosphere of multilateral confidence. Conspicuously, the 1992 Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula remains to this day a dead letter simply because of the latent state of war between the two Koreas.

Another case in point is the Middle East. Unless conditions in the region change dramatically for the better, the creation of a zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East, an idea launched at the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference in 2010, might prove a stillborn initiative. How can a meeting be convened as early as 2012 “on the basis of arrangements freely arrived at by the states of the region,” when many of those states are in turmoil, interstate relations are strained, and the threat of conflict is mounting?

If the 2012 Nuclear Nonprolifieration Treaty Review Conference is conceived as yet another opportunity to pressure Israel to join the treaty — possibly in exchange for the Arabs joining the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Biological Weapons Convention — the conference might soon reach an impasse. But the same outcome is assured if the United States and Israel conceive the conference solely as a way to isolate and force nuclear nonproliferation compliance on Iran and Syria.

The nuclear deadlock in the Middle East can be resolved only if all the regional players are ready to change old patterns of behavior. The Arab position has traditionally been that Israel cannot be offered the fruits of peace, such as recognition and normal relations, before it has paid its full territorial price — that is, a complete withdrawal from occupied Arab lands and the creation of a Palestinian state. But the Arab states nonetheless insist that even before the end of conflict, Israel unilaterally must give up its (undeclared) nuclear capabilities.

This is a futile exercise, not only because Israel would never disarm unilaterally, but also because without normal interstate relations in the region it is impossible to engage seriously in an effective dialogue on such vital issues. Indeed, Israel’s concept of “peace first and denuclearization last” was vindicated in the 1994 Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty, which speaks of a zone free of weapons of mass destruction as a goal “to be achieved in the context of a comprehensive, lasting and stable peace.”

Nor can Israel expect to have the best of both worlds — making nuclear disarmament conditional on a comprehensive peace, while simultaneously conducting a policy aimed at stalling the peace process.

There might be no better formula for progress toward a nuclear-free zone in the Middle East than a return to a concept in which two parallel tracks move toward a comprehensive Israeli-Arab peace, along the lines of the Arab Peace Initiative, and to the establishment of a zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the region. To work, the Arabs must accord to Israel key benefits of peace before peace has been formally achieved. Israel, for its part, must recommit to the doctrine of former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin that only a comprehensive regional peace agreement can prevent the Middle East from declining into nuclear chaos.

Shlomo Ben-Ami is a former Israeli foreign minister who now serves as the vice president of the Toledo International Centre for Peace. He is the author of “Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy.” © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.