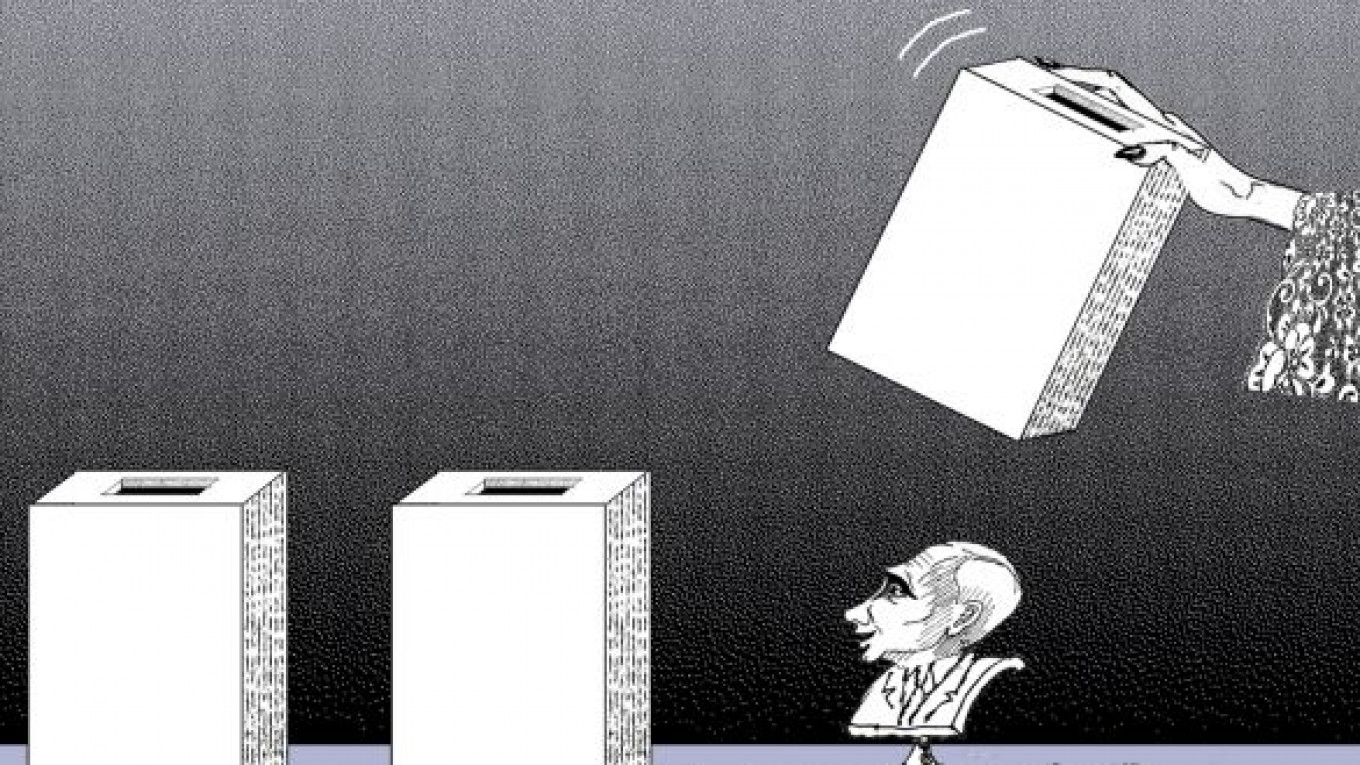

A recent scandal involving St. Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko is a vivid illustration of everything that is wrong with Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s “managed democracy.” A secret by-election was organized in two tiny St. Petersburg municipalities to exclude candidates from opposing parties and to guarantee Matviyenko’s victory in the races. Matviyenko is required by law to have a “deputy mandate” before she can be appointed speaker of the Federation Council, something the Kremlin publicly endorsed in late June.

Putin’s stance on elective government is clear — the less, the better. Notably, one of Putin’s first major policy decisions after becoming president in May 2000 was the elimination of direct elections of Federation Council senators. In 2004, Putin upped the ante by canceling gubernatorial elections, after which he appointed Matviyenko in 2006 to a second term as St. Petersburg governor. In the past year, mayors in the country’s largest cities have been de facto replaced by appointed “city managers.”

Even in those cases where federal and local elections are still held, few can be called free or fair.

With appointed government having effectively replaced elective government, it is no wonder that the level of popular discontent against governors has increased since 2004. Matviyenko is certainly at the top of the list of least-liked governors.

The main complaints from St. Petersburg residents include her support for Gazprom’s attempt to construct a 400-meter-tall tower across the Neva River from City Hall in violation of federal law, while at the same time championing the destruction of dozens of historic buildings in the city center. She also won few friends as municipal services worsened, including numerous falling icicle accidents that have resulted in at least seven deaths, and as allegations of corruption and nepotism grew.

In addition, residents bristle at the arrogance and indifference of a governor who is not answerable to the people but to the Kremlin, which believes that her most important task is to boost the popularity of United Russia.

Tellingly, during a May speech at European University, Matviyenko said: “Look at the Japanese. … They are so disciplined and calm. They don’t whine, complain or cry but march in single file. … But our population is so demanding!”

In a July Levada poll, only 17 percent of residents had a positive attitude toward Matviyenko.

Nonetheless, the Kremlin is determined to appoint Matviyenko, a loyal United Russia member and Putin confidante, as the next speaker — a spot that became vacant when former Speaker Sergei Mironov was ousted after he criticized United Russia.

Before Matviyenko can be appointed, however, she must first win a popular election in a local or federal legislature, according to a law introduced by President Dmitry Medvedev last year. Given her unpopularity and fearing a defeat in a truly free and fair election, the Kremlin was forced to use the only trick it has in these situations — election manipulation.

First, the deputies elected to the Petrovskoye and Krasnenkaya Rechka municipalities in St. Petersburg were forced to resign to create vacancies for Matviyenko’s ad hoc election. Otherwise, the Kremlin would have had to wait until Dec. 4, when State Duma and regional elections will be held.

Second, Matviyenko’s election in these two municipalities, which contain only 20,000 voters, will be held on Aug. 21 during the height of the vacation season, thus guaranteeing low voter turnout and minimizing protests from the opposition. This is reminiscent of the cowardly evasion tactic used by the Khamovnichesky District Court when it read the verdict in former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s second criminal trial on Dec. 30, a day before the entire country shut down for the 10-day New Year’s and Orthodox Christmas holidays.

Third and most important, it was first publicly announced that Matviyenko would run in the Lomonosov district in September. But, by all indications, this was only a decoy to trick real opposition candidates from Yabloko, A Just Russia and the Communist Party into thinking that they had successfully registered to run against Matviyenko in that election.

Then, Matviyenko secretly picked the Petrovskoye and Krasnenkaya Rechka districts to run in. In a clear violation of the law, this change of election venue and date was not announced in the mass media until the registration for these races was already closed, thus blocking the opposition candidates from running against Matviyenko.

The Kremlin kept the elections secret even from the head of the St. Petersburg election committee, who only found out about the change of venue and date from media reports after the registration was closed. Even more strange, Matviyenko claims that she, too, learned about the new elections only from the media.

Matviyenko told reporters Thursday that she doesn’t understand what all the fuss is about. “What was I supposed to do?” she said. “Stand out on Palace Square with a megaphone and announce the elections?”

The only candidates who apparently had inside information and were able to register to run included a cloakroom attendant, a railways worker, an unemployed man and two little-known United Russia members.

Dummy candidates are a tried-and-true trick used in Russia’s pseudo elections. Recall, for example, how Andrei Bogdanov — who was much better known as the grand master of Russia’s Masonic lodge than a politician — nominally ran against Medvedev in the 2008 presidential election. Or Sergei Mironov, who ran against Putin in the 2004 presidential election while publicly supporting him.

Given her rock-bottom ratings, the winning percentage for Matviyenko will likely be predetermined ahead of time. Meanwhile, measures needed to back into that figure — secret elections, ballot stuffing and other manipulations — are treated by the authorities as merely tactical issues.

Leaders of opposition parties said they would file a suit with the Prosecutor General’s Office and the Central Elections Commission for election fraud regarding Matviyenko’s election, but the past has shown that this is a fruitless endeavor. On Aug. 8, the Kirovsky District Court ruled that no laws were broken in the secret elections after a municipal deputy filed a lawsuit that analysts believe was a set-up — a pre-planned component of the Kremlin special operation to provide “legal justification” in advance.

Since Putin came to power in 2000, the Kremlin has used the elections commission, just like the courts, as an in-house resource to create a Potemkin democracy. But, as the Matviyenko scandal demonstrates, the facade is often so clumsily constructed that even the most naive and faithful Putin supporters see right through it. This is one reason why the nationwide ratings of United Russia — as well as its leader, Putin — have fallen.

It might be tempting to dismiss the Matviyenko scandal as just another crude special operation from Kremlin “political technologists” if it weren’t for one thing: The Federation Council speaker is the third-highest ranked official in the government, after the president and prime minister.

This is why an appeal from local opposition leaders to vote for Matviyenko in the by-election — based on the principle that the sooner she is transferred out of St. Petersburg, the better — is misguided. Although a move to Moscow would certainly be a relief to most St. Petersburg residents, it will only raise the problem of poor government and leadership to a federal level.

Matviyenko, the consummate Komsomolka, built her political career in the 1980s, rising through the ranks of the Leningrad Communist Party. In those days, there were also pseudo elections in which Kremlin-favored candidates received 99 percent of the vote against dummy candidates. The Matviyenko affair shows how little has changed in terms of how Kremlin favorites are “elected” — except perhaps that the winning percentage has been lowered somewhat.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.