Most of Europe may prefer Subway sandwiches with chicken teriyaki but the top-selling "footlong" in Russia is the BMT — or Biggest, Meatiest, Tastiest — filled with salami, pepperoni and ham. And unlike in Europe where the "veggie" option ranks in the top five favorites of Subway customers, in Russia it is nowhere to be seen.

Although the Russian preference for life's carnivorous pleasures is well known, the president of Subway in Russia, James Gansinger, said the international sandwich franchising chain has not made any significant concessions to Slavic taste buds.

Now poised to have the most branches of any Western fast-food chain in Russia — where 32 percent of all restaurants are part of a chain — Subway has come a long way since the eight-year legal battle over its flagship St. Petersburg branch with which it entered the Russian market.

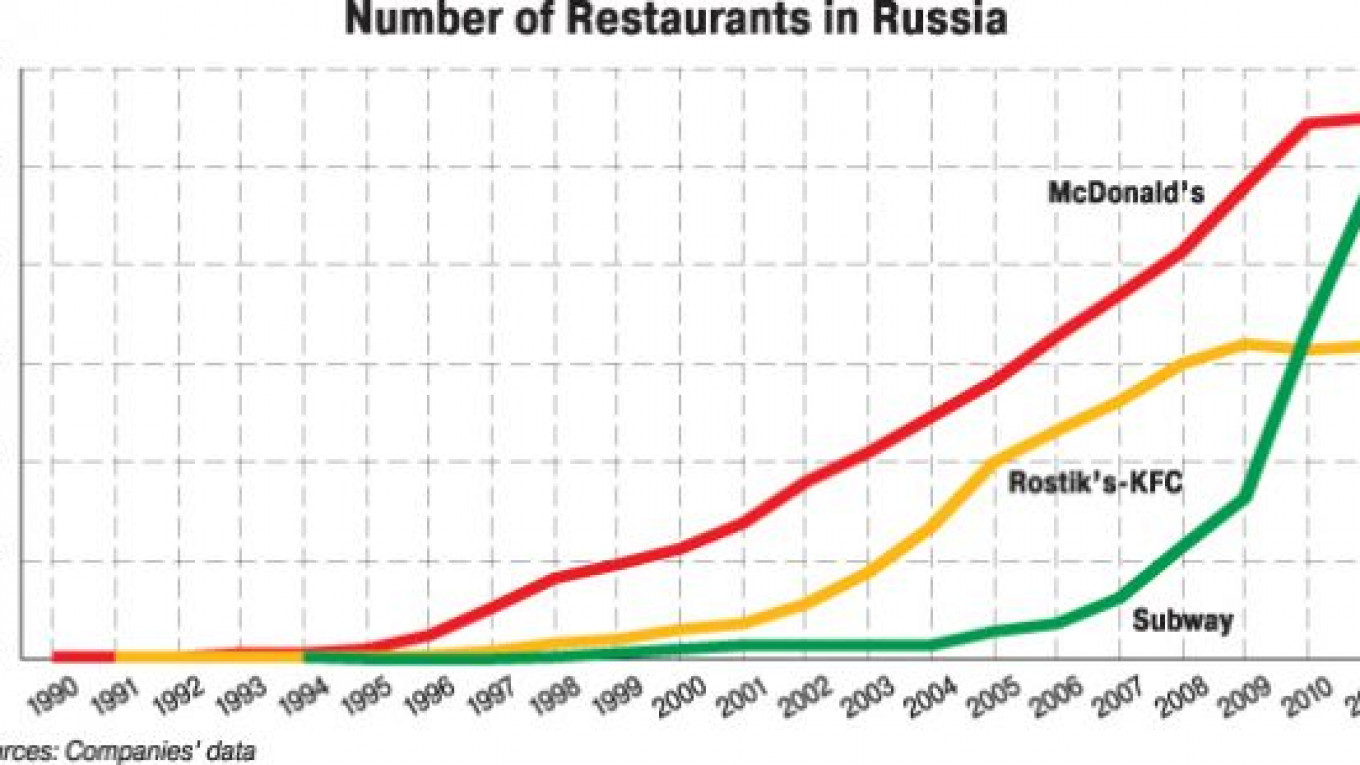

With 240 outlets, Subway slightly trails McDonalds, the current front-runner among Russia's fast-food entrants with 278 restaurants. But while Subway has made the move east of the Urals and as far a field as Vladivostok, McDonalds is only present in European Russia.

Subway also has ambitious expansion plans. The chain is aiming to open 158 new restaurants in 2011 and increase its current number of stores 11-fold by 2020, to an enormous 2,500.

"Whether we pass [McDonalds] this year or in the first quarter of next year, we're going to pass them," Gansinger said. Russia is Subway's second fastest growing world market after Brazil.

Gansinger, 65, who gave a two-hour interview to The Moscow Times in St. Petersburg, is clear that he considers Subway's success to be rooted in the system of franchising through which it operates — permitting a quick rate of expansion and providing a shield from some of the legal challenges and corruption of local business. He defined franchising as "the licensing of a proven business model for a fee or royalty."

By the end of the summer Subway will have five stores in Chita, a city of 300,000 people almost 1,000 kilometers east of Irkutsk, Gansinger said — something that could never have been achieved without franchising.

"Franchising takes you to places faster than you would ever go if you were making your own decisions in a centralized way," he said.

Subway Russia has the master franchise for Russia but directly owns only one outlet — on Nevsky Prospekt in St. Petersburg, a short walk from the Winter Palace. That restaurant is the sales leader of Subway's 38,000 global stores.

Franchisees pay $12,000 for their first franchise, $9,000 for the second and then $6,000 for every store after that. Once the store is up and running, they must pay an eight percent royalty on gross turnover.

One of the keys to Subway's rapid expansion is likely to lie in the relatively low price tag of opening a store. Gansinger estimated that while there is an outlay of between $1.5 million and $2 million to open a McDonalds or a Burger King, each Subway store costs between $150,000 and $200,000. This startup cost is shouldered by franchisees — and Russia is not known for its abundance of entrepreneurs with easy access to large amounts capital.

Sergei Mokrenko, who owns three of the six Subways in Yekaterinburg, told The Moscow Times that financial constraints were the chief brake on his expansion and confirmed that Subway's low startup costs had attracted him to the venture in the first place.

"When I opened the first restaurant [in 2003] it wasn't very profitable, but after three or four years it was so profitable that I was able to open the next restaurant entirely on credit, without diverting money from the first," he said.

Mokrenko, who also works in the alcohol production and distribution business, estimated that Yekaterinburg, a city of 1.3 million, could support a least 15 Subway stores.

Subways can also be opened very quickly once the franchising agreement has been signed. Gansinger said as little as three weeks is often sufficient, including a period of attendance by new franchisees at "training school" in St. Petersburg.

While speed is a principal benefit of the model, franchising is also a way of limiting a multinational's exposure to some of the legal problems presented by the local business environment and endemic corruption.

Numerous foreign businesses, from IKEA to Mercedes-Benz, have become embroiled in corruption scandals in Russia, slowing growth and generating a series of legal problems.

Gansinger said he has no desire to run afoul of the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, under which U.S. citizens can be prosecuted if their company engages in corruption outside of U.S. soil.

"We don't pay anybody anything," Gansinger said. "Do our franchisees do it to make things go quicker when they are trying to do something? I don't know."

Subway Russia does not deal with the permitting process to get stores open, nor does it have any contact with inspections initiated by local authorities — these are all issues dealt with by the franchisee.

"I'm not turning a blind eye to it — our company's just not involved in that process," he said.

Corporate conformity is also important. Speaking at a recent conference, Mark Hilton, vice president of Sbarro International, said that franchising "drives uniformity — uniformity to meet and exceed customer expectations."

Gansinger concurred that a rigorous adherence to the Subway model was necessary for success.

"The best franchise systems dumb everything down so that all the franchisee has to do is check the box. If he stays within the box, he'll do great — but if he tries getting out of the box, that's when he hits trouble," Gansinger said.

Soft-spoken Gansinger was one of the masterminds behind Subway's move into Russia in the 1990s. He said the idea originally arose from a pitch he and some friends from Stanford Law School made to a Soviet trade delegation in 1990.

"We didn't want to be in the restaurant business, we wanted to be in the franchising business," he said.

Although the original plan was to "clone" McDonalds' success with Burger King, he eventually settled on Subway as a cheaper alternative — but the company immediately ran into trouble.

Subway's problems, which saw the St. Petersburg store seized by their Russian partners and allegations of mafia involvement made by both sides, was ruled on by a Stockholm arbitration tribunal, a St. Petersburg City Court and the Supreme Court.

The fight became something of a test case for foreign investors in Russia — particularly as company representatives used to say Subway had been personally encouraged by Mikhail Gorbachev, keen to see Western-style "eateries" in his native country. Gorbachev was also known for lending his face to a series of Russian Pizza Hut commercials in the 1990s.

In a 2002 victory for fast-food brands, the St. Petersburg Minutka sandwich shop was shut down and the property later restored to Subway.

Referring to the dispute, Gansinger said: "There were a lot of peculiar and multilayered issues involved in those problems that had criminal and political overtones." But he added that there had been no attempts at retribution.

"We didn't emerge unscathed, but it wasn't fatal," he said.

Despite Gansinger's advocacy, however, franchising is not a universal business model among Western fast-food brands. President of McDonalds Eastern European and Russia Khamzat Khasbulatov said in March that McDonalds does not have the "motivation" to franchise in Russia, although it is a common practice by the company in other countries. Profitability was so great, he said, that the corporation saw no reason to dilute their cash flow.

Though the Russian Franchising Association maintains that there were 450 franchisors and 8,500 franchisees operating in the country in 2010, franchising has long been an ambiguous concept in Russian law. Article 54 of the legal code regulates the entire franchising relationship, referring to it as "commercial concessions."

A new bill that would put franchising on more of an official footing is currently under review in the State Duma and expected to be approved before 2012.

The concept was also showcased at the highest level earlier this year at a special panel session on the first day of the prestigious St. Petersburg Economic Forum. During the discussion, which involved Russian government representatives as well as foreign businessmen, Deputy Economic Development Minister Alexei Likhachev said that franchising is viewed as an "anti-crisis measure" because of its potential to create jobs and growth. It is also a means to integrate Russia into the world economy, he added.

Gansinger stresses that the Russian market is so underexploited that competition with other fast-food chains is not really an issue.

"The more Subways, Rostik's-KFCs and McDonalds there are in Russia, the better it is — there is a symbiotic relationship among all of us. We are [only] competing against ourselves not to screw this up," he said.

Tatyana Sharkova, 39, whose second Subway store in the Siberian city of Angarsk opened on Aug. 1, also dismissed the local competition. Though Subway's prices are steep for a provincial Russian city — the country's most popular footlong, the BMT, costs 230 rubles ($8) — she said people came to Subway because it offered something new.

And the attractions for her, the franchisee? "It's a very pleasant and respectable task," she said. "So much has been thought-out already."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.