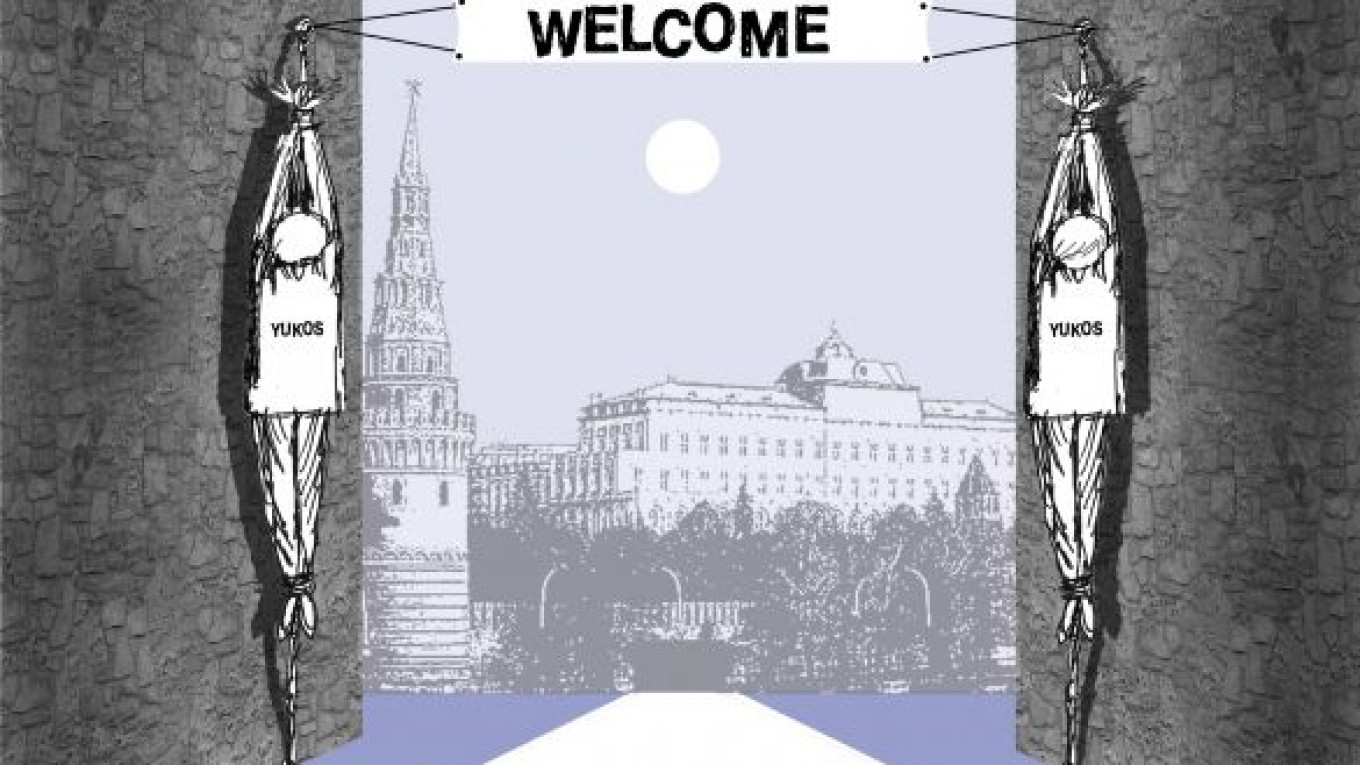

The Yukos Oil Company was forced into bankruptcy by the Moscow Arbitration Court five years ago on Monday. Its assets were seized by the state, and its top managers imprisoned or chased from the country. Its legacy of progressive corporate governance and transparency was decimated in favor of shadowy state control.

Nobody knows for sure why the Russian government destroyed its most successful post-Soviet company. It is certain, though, that the Yukos affair was a clear marker of Russia’s economic torpor and a signal to domestic entrepreneurs and foreign investors alike that their assets are simply there for the taking.

The biggest victims of the destruction of Yukos, however, are not former CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky or his business partner Platon Lebedev, who have nonetheless endured an ordeal that would test anyone. Rather it is the Russian people — on whose behalf the government supposedly acted — who have lost the most.

Although Russian stock trades around a 30 percent discount to other emerging markets and Russia’s economy lagged the other BRICs’ GDP growth by nearly 5.5 percent in 2010, according to the International Monetary Fund, the fallout from the Yukos affair cannot be measured in financial terms alone. The longer-term and far more detrimental effect is that there is now an assumption of political interference, corruption and the arbitrary use of state powers in civil disputes.

In June, the IMF confirmed that strengthening property rights and the rule of law together with reform of the judiciary and civil service are critical issues for Russia’s economic development. The fund said Russia’s poor business climate discourages investment, which, combined with political uncertainty, contributes heavily to net capital outflows. Reform or recession was the IMF’s underlying message.

Even almost a decade after Khodorkovsky’s arrest, the specter of the Yukos affair still haunts investors’ decision making. In Jochen Wermuth and Nikita Suslov’s June 16 comment in The Moscow Times titled “20 Ways to Improve Russia’s Investment Climate,” a chief investment officer of one of the world’s largest pension funds perhaps put it best: “The government stole assets from Yukos and Shell. You complain, you get expelled, like the BP manager. If you push too hard, you may even get killed in London, Vienna, Dubai or in pretrial detention. Now tell me why should I invest my clients’ money in Russia.”

With aging infrastructure in dire need of modernization, you might reasonably expect the government to bend over backward to tempt investors back and offer them, at the least, a level playing field. Eventual Russian entry to the World Trade Organization will undoubtedly help, but the decision to withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty was a big step backward, removing protection mechanisms for investments made after the date of withdrawal.

As the former majority shareholder of Yukos, we are critically aware of the need for that protection. Without recourse to binding international arbitration, we would be nowhere. Instead, an independent tribunal sitting in The Hague is currently hearing our arguments in the largest-ever commercial arbitration. Despite the Kremlin’s protests, the tribunal confirmed that Russia was fully bound by the Energy Charter Treaty until its formal withdrawal in October 2009.

President Dmitry Medvedev’s subsequent proposals to replace the energy treaty included clauses that would actually sanction discriminatory treatment against foreign investors. This measure will hardly encourage those same investors to part with the $2 trillion the Energy Ministry says is required to modernize the energy sector, increase production and improve supply.

But access to funding is not the most problematic factor for doing business in Russia. In its 2010-11 Global Competitiveness Report, the World Economic Forum reported that corruption was overwhelmingly identified by global businesses as the single most problematic factor for doing business in Russia.

The tragic case of lawyer Sergei Magnitsky shows how devastating that can be. Magnitsky, after uncovering a massive fraud allegedly perpetrated by corrupt officials in the Interior Ministry, was arrested on falsified charges and then refused medical treatment while in pretrial detention unless he testified against his client. He died in prison. Only now — three years afterward and following pressure from Western governments and international human rights organizations — has the Russian government initiated an investigation, although no one has been arrested yet.

No one should be under any illusions: Corruption was a problem before Yukos was destroyed. Some even speculate that Khodorkovsky was targeted because he was too vocal in highlighting corruption in state-owned companies. It has become much clearer since the beginning of the Yukos affair that corruption in Russia is now so endemic that it is simply a fact of life.

As the Russian government once again prepares to embark on a major state privatization program, foreign investors must clearly make their own calculations about whether the potential success of their Russian ventures outweighs the risks. For us, that calculation is simple. We have lost far too much already.

Tim Osborne is director of GML Ltd.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.