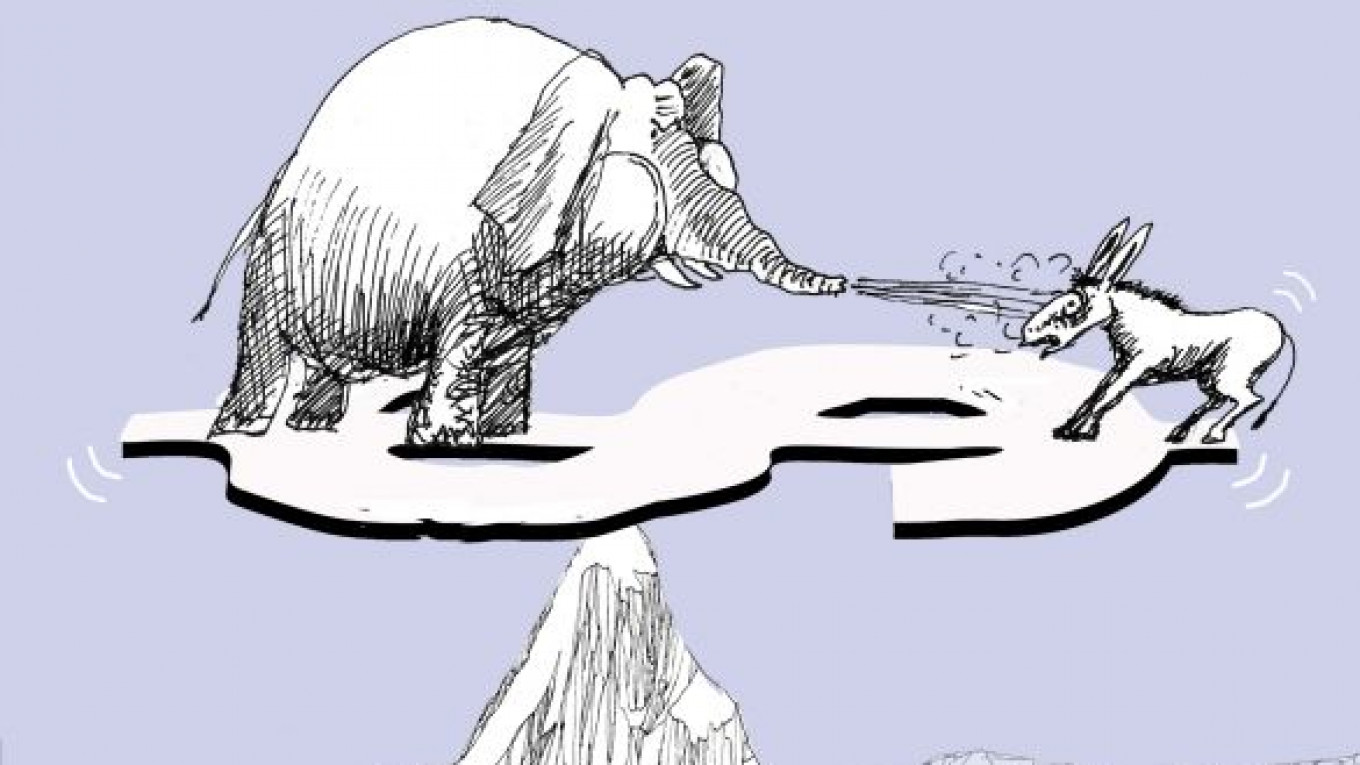

Leading U.S. lawmakers are determined to provoke a showdown with the administration of President Barack Obama over the federal government’s debt ceiling. Ordinarily, you might expect House Republicans to blink at this stage of the negotiations, but there is a hard-line minority that actually appears to think that defaulting on government debt would not be a bad thing.

These representatives — with whom I’ve interacted at three congressional hearings recently — are convinced that the U.S. federal government is too big relative to the economy and that drastic measures are needed to bring it under control. Depending on your assessment of Tea Party strength on Capitol Hill, at least a partial debt default does not seem as implausible as it did in the past — and recent warnings from ratings agencies reflect this heightened risk.

But the consequences of any default would, ironically, actually increase the size of government relative to the U.S. economy — the very outcome that Republican intransigents claim to be trying to avoid.

The reason is simple: A government default would destroy the credit system as we know it. The fundamental benchmark interest rates in modern financial markets are the “risk-free” rates on government bonds. Removing this pillar of the system — or creating a high degree of risk around U.S. Treasuries — would disrupt many private contracts and all kinds of transactions.

In addition, many people and firms hold their “rainy day money” in the form of U.S. Treasuries. The money market funds that are perceived to be the safest, for example, are those that hold only U.S. government debt. If the government defaults, however, all of them will “break the buck,” meaning that they will be unable to maintain the principal value of the money that has been placed with them.

The result would be capital flight — but to where? Many banks would have a similar problem: A collapse in U.S.Treasury prices would destroy their balance sheets.

There is no company in the United States that would not be affected by a government default — and no bank or other financial institution that could provide a secure haven for savings. There would be a massive run into cash, on an order not seen since the Great Depression, with long lines of people at ATMs and teller windows withdrawing as much as possible.

Private credit, moreover, would disappear from the U.S. economic system, confronting the Federal Reserve with an unpleasant choice. Either it could step in and provide an enormous amount of credit directly to households and firms — much like the old Soviet Union’s central bank — or it could stand by idly while gross domestic product falls 20 percent or 30 percent, a decline that we have seen in modern economies when credit suddenly dries up.

With the private sector in free fall, consumption and investment would decline sharply. The United States’ ability to export would also be undermined because foreign markets would likely be affected. In any case, if export firms cannot get credit, they most likely cannot produce.

The Republicans are right about one thing: A default would cause government spending to contract in real terms. But which would fall more, government spending or the size of the private sector? The answer is almost certainly the private sector, given its dependence on credit to purchase inputs. Indeed, take the contraction that followed the near-collapse of the financial system in 2008 and multiply it by 10.

The government, on the other hand, has access to the Federal Reserve and could therefore get its hands on cash to pay wages. With the debt ceiling unchanged, this would require some legal sleight of hand. But the alternative would clearly be a collapse of U.S. national security. Soldiers and border guards have to be paid, the transportation system must operate, and so on.

Issuing money in this situation would almost certainly be inflationary, but the Federal Reserve might conclude otherwise. After all, the United States has never been in this situation before, credit is now imploding, and the desperate credit-expansion measures implemented in 2008 proved not to be as bad as the critics feared.

So this is what a U.S. debt default would look like: The private sector would collapse, unemployment would quickly surpass 20 percent, and, while the government would shrink, it would remain the employer of last resort.

The House and Senate Republicans who do not want to raise the debt ceiling are playing with fire. They are advocating a policy that would have dire effects and that would accomplish the opposite of what they claim to want. A default would immediately make the government more, not less, important.

The only law that Congress cannot repeal is the law of unintended consequences.

Simon Johnson, a former chief economist of the IMF, is a professor at the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, and co-author, with James Kwak, of “13 Bankers.” © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.