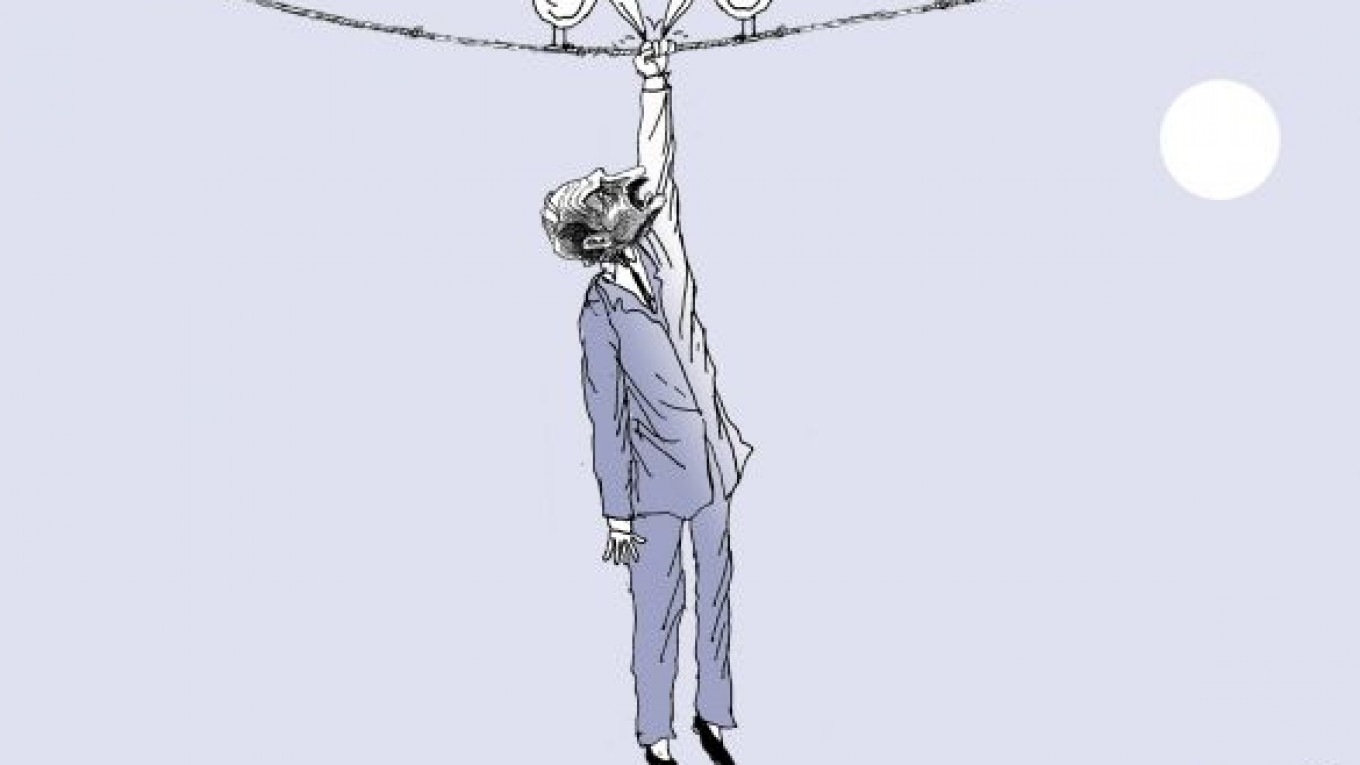

Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko is a master of political survival. But, following a recent 64 percent devaluation of the currency, the clock appears to be running out on his prolonged misrule.

Lukashenko was forced by the removal of Russian oil-price subsidies in 2009 to beg, borrow or steal enough funds to keep Belarus’ economy from collapsing. He tricked the International Monetary Fund into extending a $3.4 billion loan, promising freer elections in December — only to burn that bridge with a brutal crackdown when faced with an adverse election result and the largest protests his regime had ever seen.

Now Russia has taken a harder line, demanding a high price for loans that are, in any case, insufficient to save the regime. As a result, the Belarussian economy is in free fall, and Lukashenko’s days appear to be numbered.

Lukashenko used the IMF money to keep his state-dominated, inefficient and subsidy-dependent economy afloat through the 2010 election. But, shortly after the vote, signs of trouble became visible. During a visit I made to Belarus in January, officials refused to forecast gross domestic product growth in 2011, except to say that it would be lower. At a time when most of Europe was starting to recover from the 2008 recession, Belarus was going in the opposite direction.

Then, crisis erupted in May, when the country ran low on foreign-currency reserves and traders could not purchase the dollars they needed. The currency, which traded at 3,000 rubles to the dollar in January, collapsed to 8,000 to 9,000 in mid-May, and the government was forced to devalue the official rate from 3,010 to 4,950 while continuing to restrict banks’ ability to buy foreign currency.

As inflation skyrocketed, Belarussians bought anything of value that they could, from food to used cars. Belarus, which had been known (and praised by some) as a socialist haven in Europe, with a relatively generous welfare state and decent, if low, wages, suddenly has become an economic basket case. The public is reaching breaking point. On June 7, about 100 cars blocked roads in central Minsk to protest a 30 percent increase in fuel prices — a daring act in Europe’s most formidable police state.

The swiftness of Belarus’ economic meltdown reflects the directness of its cause. Russia had been financing Lukashenko’s shabby paradise, and then it decided to stop paying. Without enough dollars flowing in from transit fees for Russia’s oil and gas exports to Western Europe, the country was bankrupt.

Russia had simply seized the opportunity presented to it by Lukashenko’s bizarre post-election crackdown, in which he used disproportionate force to clear the streets and imprisoned hundreds of activists, including seven of the presidential candidates who had run against him. Presidential candidate Andrei Sannikov was recently sentenced to five years in prison for taking part in election-night protests.

The outcry from a betrayed West was loud and visceral. Lukashenko had lured the IMF and the European Union into providing support for his economy during the global financial crisis. The presidents of Italy and Lithuania had made high-profile visits prior to the elections as part of a policy of “engagement.” The foreign ministers of Poland, Germany, and Sweden traveled to Minsk during the fall of 2010 to meet with Lukashenko, civil-society groups and opposition leaders. At the end of this trip, Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski announced the possibility of a $4 billion EU aid package should Belarus hold a free and fair election.

When these hopes were dashed, the West reacted with stunned disbelief and anger, reinstating sanctions on 156 top Belarussian officials and members of Lukashenko’s family.

More important, Lukashenko’s break with the West left him at the mercy of Russia. The Kremlin, sensing his weakness, decided to bargain hard. They threatened to renege on their own generous pre-election promises of aid unless Belarus surrendered stakes in the country’s most lucrative companies, including Beltransgaz, the gas-pipeline network, and Belaruskali, the potash miner, among others.

This has put Lukashenko squarely on the horns of a dilemma. He badly needs Russia’s money, but his domestic support is based on defending Belarus’ fragile sovereignty. Some would regard the sale of the economy’s crown jewels as tantamount to national betrayal, possibly a capital crime. A bombing in the Minsk metro in April that killed 14 and injured hundreds may have been a grim foretaste of the political risks involved.

Negotiations with Russia dragged on, and the country ran out of money. Now Russia says that it will provide money in the form of loans, promising annual tranches of around $1 billion, but only if Belarus makes sufficient concessions. In early June, Lukashenko signed a deal: Belaruskali is the first enterprise on the table, in exchange for an $800 million loan.

Lukashenko’s only alternative to losing sovereignty to Russia is to go begging to the IMF. In that case, he would face “shock globalization” and political death through free and fair elections. On the other hand, the IMF could go soft and shovel more money at him, possibly in exchange for the release of political prisoners.

But the IMF should not be in the ransom business. The West should send the same message to Lukashenko that it has sent to Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad: No IMF money to prolong the life of a brutal regime. No loans for prisoners. It is time for Lukashenko to go.

Mitchell Orenstein is professor of European studies at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced and International Studies in Washington. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.