The past 20 years have seen a rethinking of many assumptions that were considered indisputable in the early 1990s. Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” never came, and democratic regimes did not spread throughout the world. Global disarmament has not become a reality, while there are more military interventions around the world today than ever before.

But more important, the “post-industrial” model has not become the predominant one as anticipated. On the contrary, we are witnessing a renaissance of industrial countries and the rise of resource economies, even while the United States and Europe are grappling with serious financial problems.

There is a simple explanation for this trend. After launching the technological revolution, the West has created powerful competition in the information products sector that has led to a rapid decline in prices for those goods. Technologies that were rare in the 1990s are so widespread today that they are almost considered free public goods. Take, for example, Wi-Fi in restaurants and cafes.

At the same time, however, the greatest profits have gone not to those who first developed the technologies but to companies that mass-produce the hardware incorporating them. For example, mobile phone technology was invented in the United States, but Finland’s Nokia led in mobile phone sales for many years. The GPS system was also created in the United States, but more cars in Europe make use of it than in the United States. China has long been the largest exporter of computers, home electronics and mobile phone-related products. What’s more, as mobile phone and computer technologies have dropped in price and the standard of living has risen in various countries, the opportunities for growth in industrialized countries appear limitless.

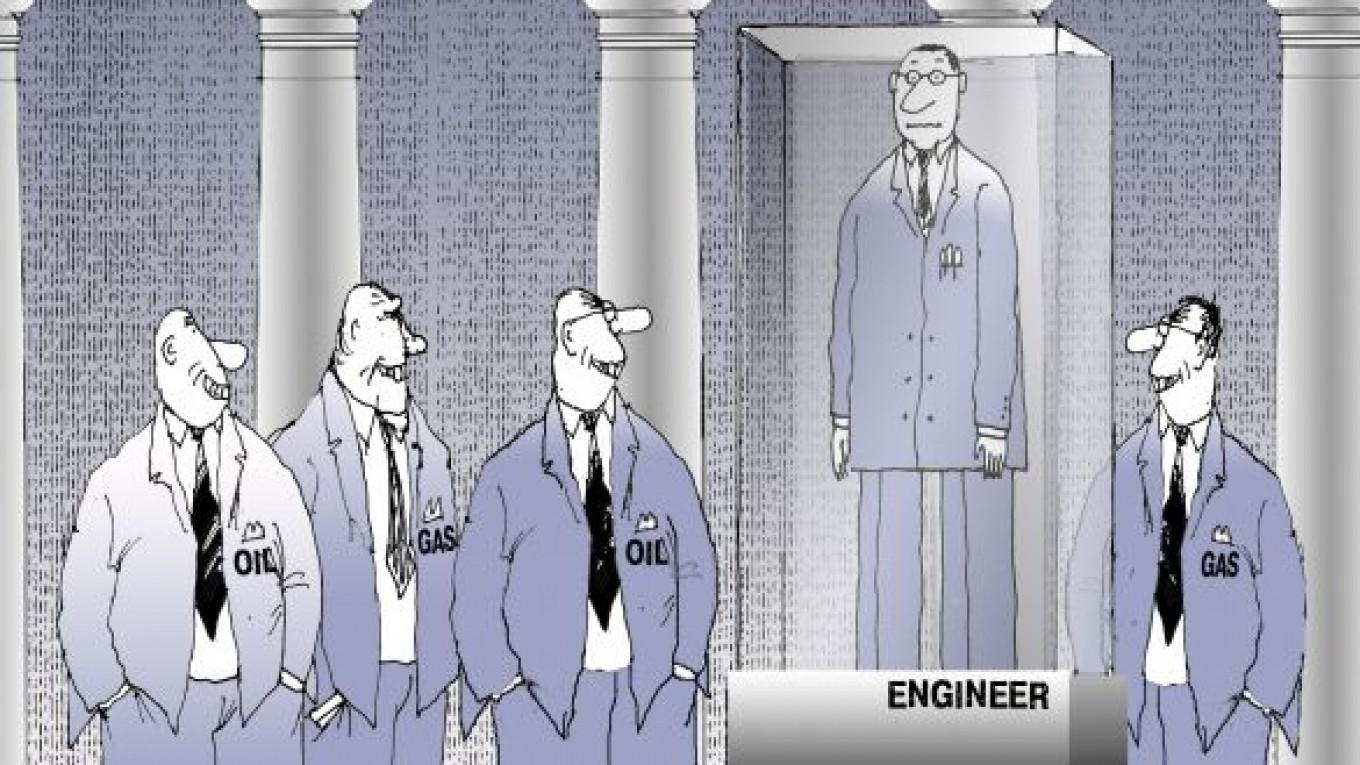

As a result, there is great potential today for an industrial renaissance. Economist Vadim Malkin argued in a Nov. 17 Vedomosti op-ed that over the past 25 years, most countries that spent more than 2.5 percent of their gross domestic product on research and development showed far less economic growth than industrialized countries that spent less than 1 percent of GDP on research and development but actively borrowed advanced technologies from abroad. The leaders in technology, thus, have been those countries that excel in technical and engineering education and are able to produce a large class of highly skilled workers.

Unfortunately, Russia is an exception to this rule. In recent years, 39 percent of all Chinese university graduates earned engineering degrees, compared to 28 percent in Germany and fewer than 14 percent in Russia. The system of vocational training has been almost completely destroyed since the Soviet collapse. The number of highly skilled industrial workers increased 2.8 times in China between 1995 and 2010 but more than halved in Russia over the same period.

Russia’s leaders have been speaking about the importance of technological breakthroughs and the need to build an “information society.” But new technologies themselves have limited value if the country cannot manufacture goods based on this know-how. For example, the United States, the most technologically advanced country in the world, earns only 4 percent of its export income from patents and licenses. But in Germany, manufactured goods account for more than 87 percent of all exports, of which more than 40 percent contain technological components.

In the 21st century, technology can bring wealth to a country that can produce finished goods that are in demand on the global market and competitive domestically. In their pursuit of creating an innovation-based, modernized economy, Russian authorities need to learn this lesson and focus more of their attention on improving the country’s industrial and manufacturing capabilities. A good place to start would be by reducing the tax burden for industrial enterprises.

It is unfair to compare Russia’s economic development with China because the countries are far too different. A better comparison would be with Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, which have all recently emerged as Europe’s new industrial powerhouses. Take, for example, one striking figure: More automobiles were manufactured in Slovakia in 2009 than in all of Russia.

Russia needs to re-establish its prestige as a leader in technical and engineering-based professions. To be sure, this economic shift requires many years, if not decades, but a few signs of progress can already be discerned. For the first time, the 2011 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum will include a session on training and developing engineers to help rebuild Russia.

This is one small but important indication that Russia is coming to see industrialization as a key element toward modernization.

Vladislav Inozemtsev is a professor of economics at the Higher School of Economics, director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies and editor-in-chief of Svobodnaya Mysl. He will moderate the session “Training Engineers: Building on Fundamentals of Russia’s Economy” at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum on Saturday from 10 to 11:15 a.m.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.