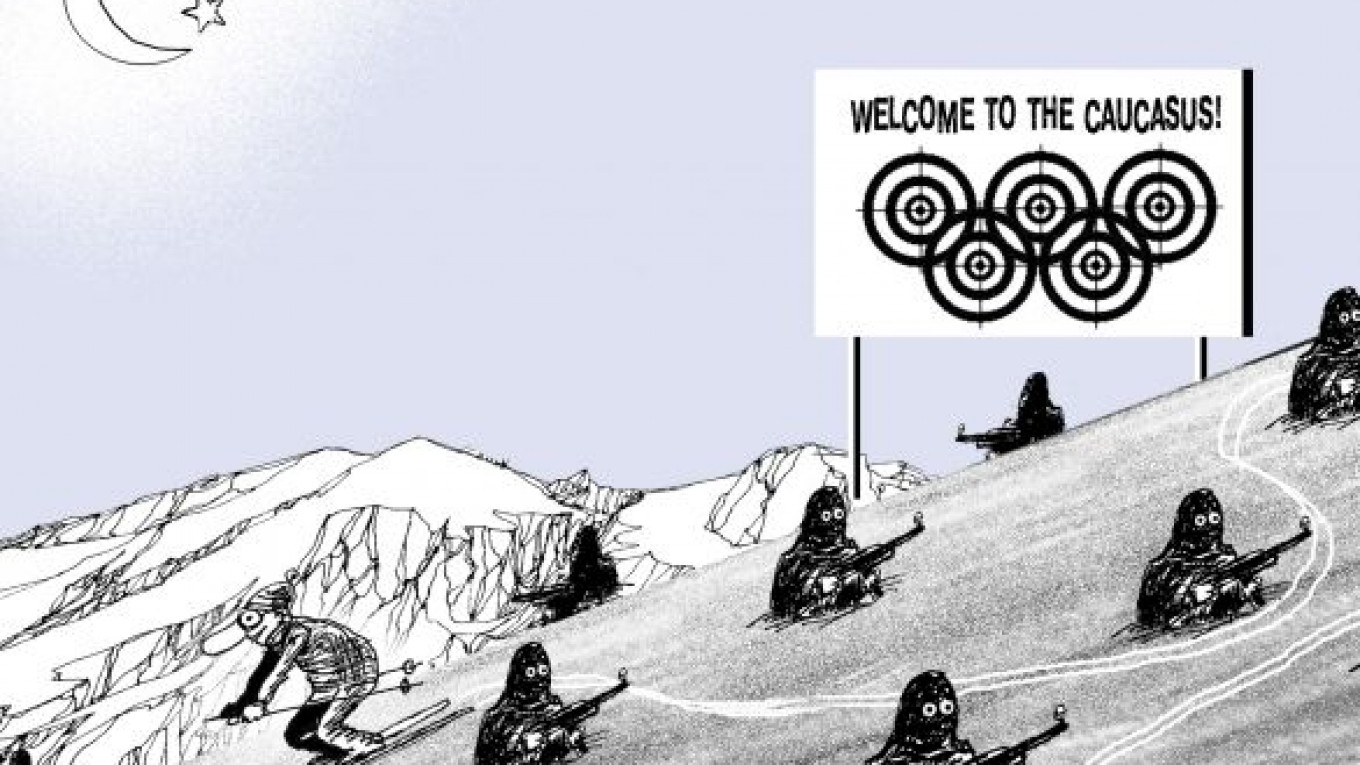

The Russian authorities have recently begun showing off the massive security measures being implemented ahead of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. They have good reason to be worried — and not only for the safety of athletes and spectators.

The violence in the North Caucasus is becoming less a serious regional conflict and more an existential threat to the entire country, an evolution that reflects almost all of the mistakes, failures and crimes of the post-Soviet leadership.

Two horrific wars with local separatists — in 1994-96 and 1999-2006 — have been fought over Chechnya, presumably to secure Russia’s territorial integrity. Russians fought these wars to demonstrate to the Chechens that they, too, were citizens of the same country. Moscow did so by destroying Chechen cities and villages with artillery shells and aerial bombardment, as well as abducting, torturing and killing civilians. It should surprise no one that the Chechens — and other peoples of the Caucasus — do not feel very Russian.

In reality, Russia has lost the war against the Chechen separatists. The winner was Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, one of the field commanders in the fighting. Ostensibly, he is an appointee of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, but in reality he is virtually independent of the Kremlin, which pays him substantial financial support not only for his formal declaration of loyalty, but also for his public embrace of Putin.

The war against separatism in the North Caucasus has now evolved into the war against Islamic fundamentalism. Ignited by the violence of the Chechen wars, Islamist-sponsored terrorism has spread widely in the region as Russian policies, similar to those during the Chechen war, increase the number of Islamic radicals.

President Dmitry Medvedev, for example, has called for extremists to be “burned to ashes.” He also called for terrifyingly broad punishment, including of those “washing linen and preparing soup for terrorists.” Given the morality of federal forces, Medvedev should have understood that such rhetoric could result only in a significant increase in brutality and extrajudicial killings all over the North Caucasus.

The resulting mayhem has served only to spawn new suicide bombers willing to bring fresh terror to Russia’s heartland. Indeed, the paradox today is that Islamic extremists seem to be losing influence in the Arab world while strengthening their position in the North Caucasus, where the Kremlin has fought a 12-year war without understanding the scope of the tragedy taking place: a civil and ethnic war for which the Kremlin itself bears significant responsibility.

After all, the tribute that the Kremlin pays Kadyrov and the corrupt elites of the other Caucasus republics has purchased palaces and gold pistols for men who are driving the region’s young, unemployed and disadvantaged down the path of Islamic revolution. Across the North Caucasus, a generation has grown up absolutely lost to Russia — and increasingly susceptible to recruitment into the ranks of Allah’s warriors.

A nearly unbridgeable mental gap now separates Russians and Caucasus natives. Young nationalists are fond of marching though the streets of Moscow and other cities carrying anti-Caucasus banners, perceiving themselves as being on the winning side in the region.

In the hearts and minds of people on both sides, Russians and Caucasus natives are becoming increasingly alienated from each other. But neither the Kremlin nor its North Caucasus allies are ready for formal separation. Russia remains wedded to its phantom imperial illusions about a “zone of privileged interests” extending far beyond its borders, while Chechnya, starting with Kadyrov, is ruled by independent autocrats happy to accept handouts from the federal budget.

The irony is that, like the Kremlin and its allies, the Islamic fundamentalists do not want to separate. They dream about a caliphate that would include much more of Russia than the North Caucasus.

Recently, Medvedev convened a large public meeting in Vladikavkaz. He accused anonymous enemies — presumably including Western governments — of pursuing an agenda to destroy Russia, and he encouraged his security officials to push back. In Medvedev’s mental universe, savage reprisals today will somehow turn the North Caucasus into a zone of international ski tourism tomorrow.

That is not likely to happen. The day after Medvedev’s departure from Vladikavkaz, terrorists blew up the ski lifts at the resort in Nalchik, not far from Sochi, where much more will be at stake for Russia in 2014 than winning medals.

Andrei Piontkovsky is a political scientist and a visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.