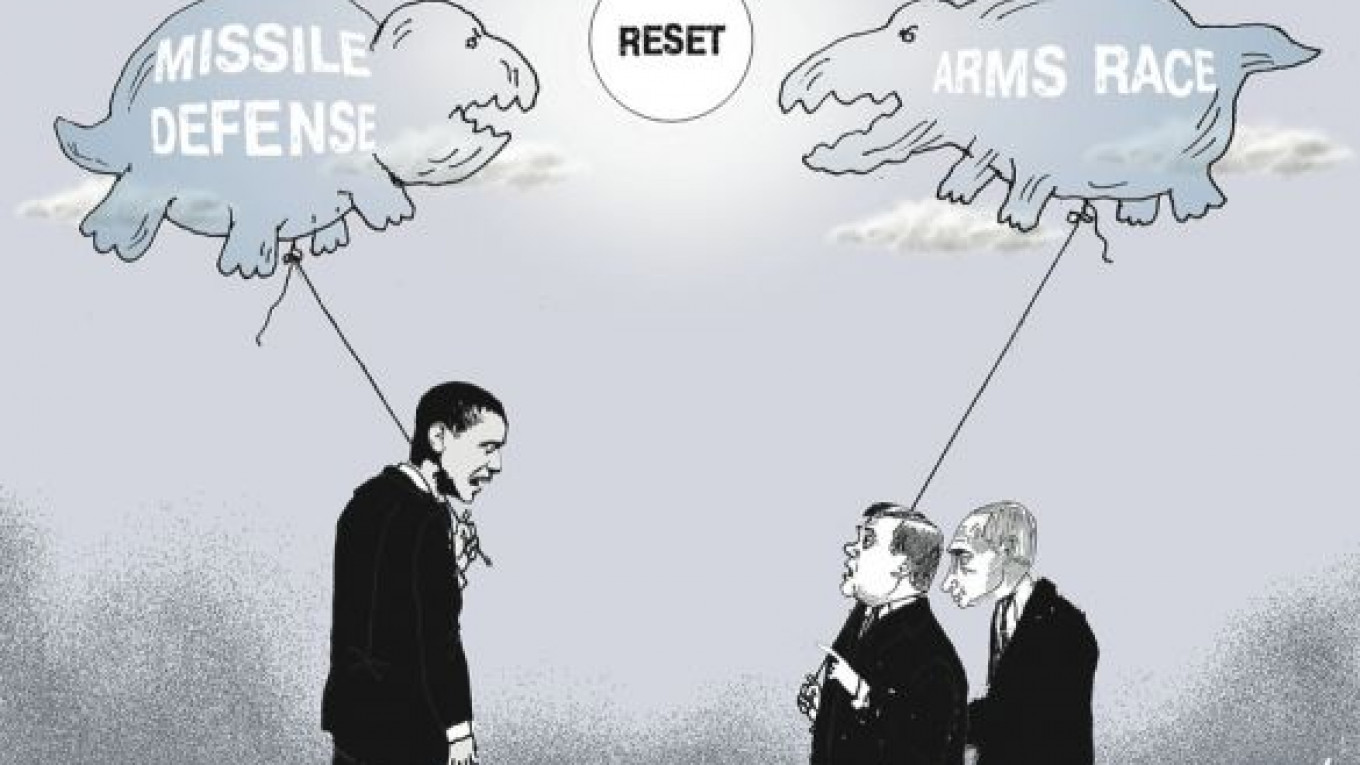

Anyone following the statements made by U.S. President Barack Obama and President Dmitry Medvedev during the recent Group of Eight summit in France would have to conclude that the two leaders completely misunderstood each other. Obama spoke about the success of the reset in U.S.-Russian relations while Medvedev, unable to hide his irritation, promised an arms race by 2020.

During NATO’s summit last year in Lisbon, the alliance announced its plans to create a European missile defense system. In turn, Medvedev proposed that this system should be built jointly with Russia. At first, everyone was elated at the idea because it suggested that Moscow no longer viewed the West as its adversary.

But the euphoria didn’t last long. After rejecting Moscow’s suggestion for a “sector-based” approach to missile defense in which each country would be responsible for intercepting enemy missiles passing over its own airspace, the Kremlin returned to its old position that NATO’s primary intention in creating a missile defense system was to undermine Russia’s nuclear deterrent capability.

The latest round of bickering over missile defense shows once again how Russia — and the United States — treat the issue as a political football rather than a legitimate national security issue.

The idea of achieving absolute protection against a missile strike from any country on U.S. territory has been extremely popular with Americans ever since U.S. President Ronald Reagan first proposed his “Star Wars” program. U.S. President George W. Bush, in an effort to exploit that popular support, withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002 and announced plans to deploy elements of the U.S. missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic.

The first question everybody asked was: Which countries are capable of launching a missile attack against the United States or Europe? Iran, Syria and North Korea still need many years under the best of circumstances before they would be able to do this.

Then-President Vladimir Putin got into the game by accusing Bush of trying to use missile defense to weaken Russia. In fact, experts maintained that the 50 or so interceptor missiles Bush planned to deploy in Central Europe could have destroyed no more than a dozen of the 1,500 or so warheads that Russia has.

But nobody was interested in having a serious discussion on the subject. The issue of missile defense has become a perfect boogeyman, which the Kremlin manipulated for internal political purposes in the same way as it has done with the issue of NATO expansion.

Nonetheless, Obama tried to calm Moscow’s nerves over missile defense by rejecting the Bush administration’s missile defense architecture and proposed a more modest version using the sea-based Aegis system. Its Standard Missile 3, or SM-3, intercepters have a range too short to destroy Russia’s intercontinental ballistic missiles. The SM-3 intercepters are only capable of striking intermediate range missiles — the very same weapons that Russia and the United States eliminated from their arsenals 25 years ago.

But Moscow seized on a single sentence contained in a U.S. document on missile defense development stating that in 2020 a new Block IIB modification will give the intercepter missiles the capability to intercept intercontinental missiles. But the document contains no tactical or technical specifications of the modified intercepter or of the configuration of the European missile defense system in general. The omission was not a deliberate attempt to conceal an insidious plan against Russia, but stems from the fact that nobody knows exactly how the fourth phase of the European missile defense system will develop.

In reality, the idea of European missile defense was less driven by military necessity as it was to achieve a political goal: to demonstrate that the Euro-Atlantic bond is stronger than ever.

But this ambiguity provided the General Staff grist for its anti-U.S. and anti-NATO mill. Military hawks dreamed up scenarios in which dozens of U.S. destroyers would soon be hiding among Norwegian fjords, waiting day and night to intercept Russian missiles fired as a counterstrike after a U.S. first strike.

Every Russian initiative on missile defense, including its proposal for a sectoral missile defense system, has been a bluff. And Medvedev’s threat to unleash another arms race is even more of a bluff. According to Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, Russia can attain the limits for nuclear delivery vehicles imposed by the New START treaty — 700 vehicles — only in 2028, and even this will be difficult to attain.

Today, the United States has twice as many delivery vehicles as Russia. With this huge gap in nuclear force capabilities, which Russia will find difficult to close, Medvedev’s threats of an “arms race” can hardly be treated seriously.

Why, then, all the Kremlin bluster about missile defense? It’s all about the 2011 and 2012 elections in Russia. The electorate is best mobilized when the Kremlin can create the image of a treacherous enemy, particularly one that can organize a subversive Orange or Rose revolution within Russia. This scare tactic was remarkably successful in 2007, prior to State Duma and presidential elections. Apparently, Russia’s leaders are trying it again now.

At his meeting with Medvedev, Obama said the United States and Russia had managed to achieve a reset in relations. But when you install two conflicting programs on one computer, the system breaks down.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.