It is often said Russians don’t smile much, while Americans smile too much.

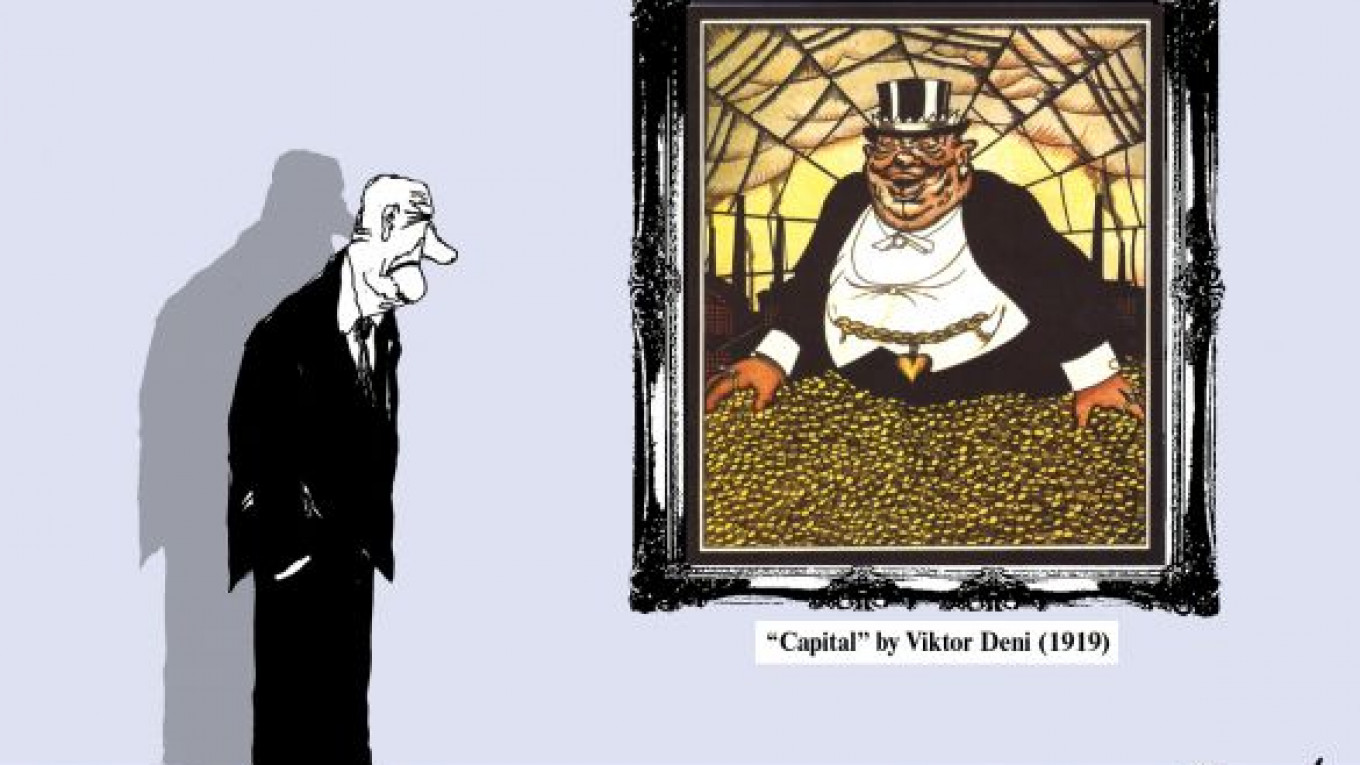

In general, the American smile has a terrible reputation in Russia. The campaign started in the early Soviet era. Look at the sinister smiles on old agitprop posters of caricatural “U.S. imperialists” wearing trademark cylinder hats, smoking cigars, salivating and smiling as they relished their piles of money and power over the world’s exploited classes.

Later, starting from the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras and continuing until the late 1980s, the Soviet print and television media carried regular reports called “Their Customs,” which focused on contemptible bourgeois lifestyles in the United States and other Western countries.

A favorite topic of these reports was the infamous American smile. Soviets were told that behind the superficial American smile is an “imperialist wolf revealing its ferocious teeth.” The seemingly friendly American smile, Soviets were told, is really a trick used to entice trusting Soviet politicians to let their guard down, allowing Americans to deceive them both in business deals and in foreign policy.

An example that Russian conservatives love to quote: when then-U.S. Secretary of State James Baker in February 1990 reportedly used his “charming, cunning Texas smile” to trick then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev into agreeing to a unified Germany as long as the United States pledged verbally that NATO would not extend “an inch further” to the east.

The image of an insincere, insidious American smile was used in Soviet propaganda mainly to depict U.S. politicians, “warmongers” from the military-industrial complex and other “bourgeois capitalists,” but it also applied to normal Americans, who, Soviets were told, use smiles to betray one another in business and personal relations.

The message was clear: Feel fortunate you live in the Soviet Union, which has an honest moral code of conduct, where people trust one another and where there is complete harmony at work and among different nationalities.

Unlike the American smile, the Soviet smile was sincere, according to the official propaganda, because Soviets had so much to be happy about — guaranteed jobs, free education, inexpensive sausage, tens of thousands of nuclear weapons, a huge Soviet empire that could throw its weight around the world and, if that were not enough, Yury Gagarin, who beat the Americans to space.

In reality, the only smiles people saw in public were the ones depicted on ridiculous Soviet propaganda posters showing the idyllic workers’ paradise.

During the perestroika era, the American smile was a common reference point when the topic of rude Soviet service was discussed. In an often-quoted exchange that took place on a late-1980s television talk show, one participant said, “In the United States, store employees smile, but everyone knows that the smiles are insincere.” Another answered, “Better to have insincere American smiles than our very sincere Soviet rudeness!”

In post-Soviet Russia, business motivators often preach the value of implanting U.S. know-how — the “technique of smiling” — among employees in stores, restaurants and other service-oriented companies. In this spirit, McDonald’s restaurants in the 1990s even included a “smile” on its Russian menu together with the price: “free.”

But there is a large political component that ultimately decides whether a nation's society is smiling or grim. One key factor is how democratic and open a country is. The 2008 World Values Survey found that freedom of choice — and not simply wealth — has a strong impact on the happiness of people.

Indeed, it can be hard to smile when you are not free from government abuse, corruption and lawlessness, when simple things — such as finding a spot for your child in kindergarten, getting basic documents from a government agency or receiving medical care — can’t be done without paying bribes. It can be hard to smile when you know you are paying more than in the West for the same goods and earning lower salaries because of the ubiquitous “corruption tax” that is passed down to consumers and employees. Businesspeople would surely smile more if they could operate their businesses without being “terrorized” by the extortion of bureaucrats and competitors.

Adrian White, a British psychologist and author of the “World Map of Happiness,” says that “a nation’s level of happiness is most closely associated with health levels, followed by wealth and then education.” On all three criteria, Russia fared poorly on White’s index, coming in at No. 167 among 178 countries surveyed. (Denmark, Switzerland and Austria were the three happiest countries. At the bottom were the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe and Burundi.)

It is often said life is like a mirror; we get the best results when we smile at it. This may be true if the mirror is normal. But in Russia, the mirror is horribly distorted by corruption, arbitrary rule, lawlessness, a weak civil society and a low level of freedom.

It is a primitive stereotype and myth that Russians are doomed to be gloomy and morose. The problem has little to do with Dostoevsky or the cold climate and much more to do with the huge hall of distorted mirrors that we pass through every day. It was the government that put up many of these mirrors, and they need to be gutted. The Kremlin should start this reconstruction with its own halls and corridors.

In the meantime, though, we still have reason to smile. Smiling is not a mechanical technique or function — after all, you can train a monkey to mimic a smile — but a much deeper emotional state of mind. To put it simply, each person can decide whether or not to be happy, no matter the circumstances.

While McDonald’s ultimately removed the “smile” choice from its Russian restaurants, smiles are not off the menu.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.