U.S. President Barack Obama recently announced that the NATO-led operation against Libya had reached a stalemate. At the same time, however, he hopes Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi will soon be forced to step down. Obama’s statement is remarkably similar to U.S. President Lyndon Johnson’s comments at the peak of the Vietnam War.

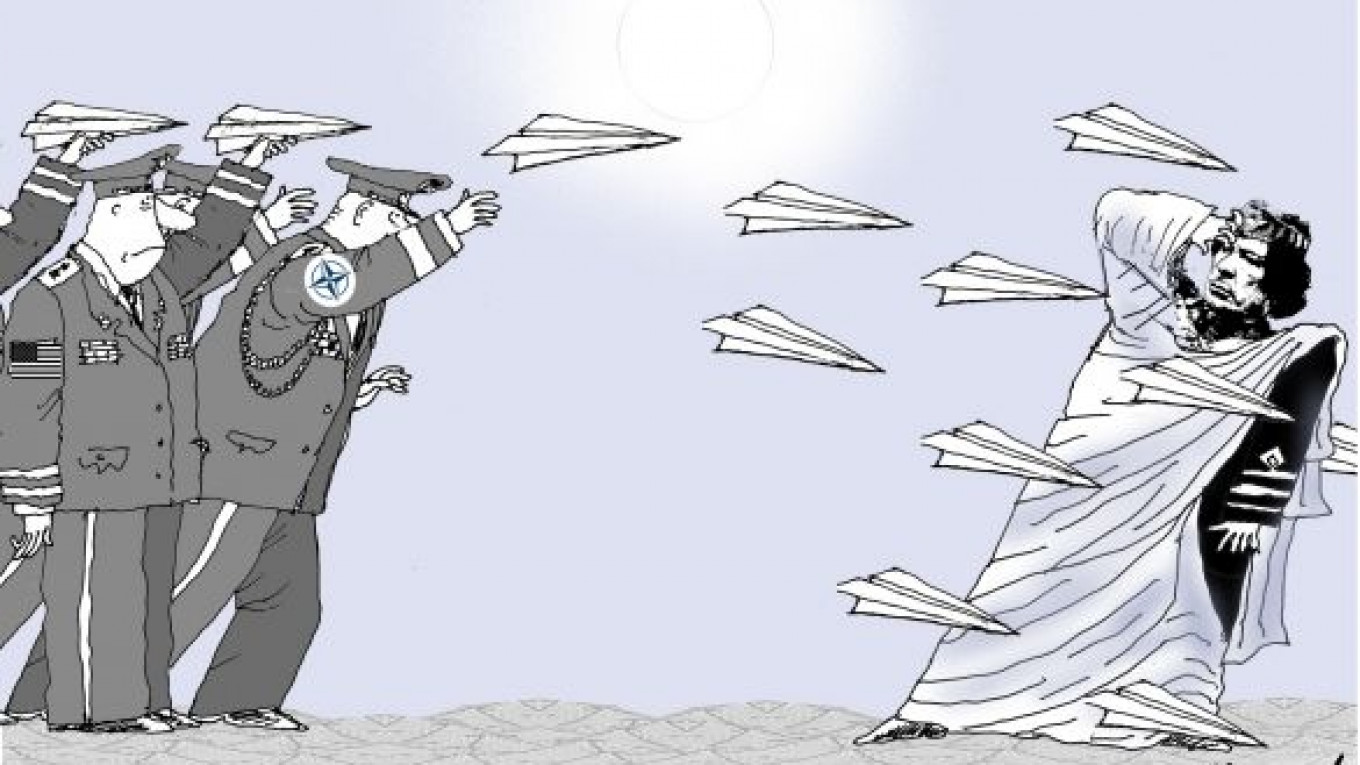

Beginning with the first Gulf War, we have become accustomed over the past 20 years to Western military interventions in which the enemy’s defenses were devastated in the first few days by overwhelming air attacks But the Libya operation is different because NATO member countries as a whole — and the United States in particular — have shown so little resolve.

Almost two centuries ago, German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz coined the oft-quoted phrase, “War is a continuation of political relations.” By extension, no war should be launched before allies have reached agreement on both their political and military strategies.

In the early 1980s, U.S. Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger formulated principles for conducting military operations (although it is often attributed to then-U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, who implemented them brilliantly in the 1990s). According to Weinberger’s principle, massive and overwhelming military force should be applied without political constraints to quickly break down the enemy’s will to resist. This is exactly how most U.S. military operations have been carried out in the past 15 years, from Yugoslavia to Iraq.

The main reason for Washington’s passivity in the Libyan operation is that Obama did not want to get involved in another war. At the same time, Washington understood in mid-March that it was necessary to bomb Gadhafi’s key military targets quickly — even without the necessary preparations — to avoid a humanitarian catastrophe in Libya.

But now, a month after the Libyan military operation began, it is clear that Obama did not embrace Weinberger’s principle in Operation Odyssey Dawn. In the first weeks of the Afghanistan operation in 2001, 300 coalition combat aircraft were used, while in Libya only 70 were used. With U.S. forces so limited in the Libyan operation, NATO’s strike and surveillance systems — including satellites, drones, aircraft and precision weapons — are far less effective. During the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan, for example, only about 10 minutes elapsed between a target’s detection and destruction. In Libya, that process takes 90 minutes.

One of the problems for NATO is that it set unrealistically high expectations for itself as an arbitrator of global conflicts. Take, for example, the alliance’s new strategic concept, released in November, which states: “Where conflict prevention proves unsuccessful, NATO will be prepared and capable to manage ongoing hostilities. NATO has unique conflict management capacities, including the unparalleled capability to deploy and sustain robust military forces in the field.” Thus, NATO set a trap for itself, obligating itself to intervene in a wide range of internal conflicts across the globe.

Having reluctantly agreed with France and Britain to begin the Libyan operation on March 19, Washington within days started to scale back its involvement, and the command structure was shifted to NATO, a direct signal that the United States did not want to take direct responsibility for the operation’s outcome.

While Washington did not want to unleash its full military might against Gadhafi, France and Britain do not have sufficient military means to conduct an effective air campaign on their own. One reason for this is that for the past 20 years, France, Britain (along with other leading European countries) have made drastic cuts to their defense budgets and were more than willing to shift responsibility for resolving global security problems to the United States.

Since NATO has not initiated a massive military assault against Libya, Gadhafi’s forces remain largely intact, and he has used that to his advantage. In fact, after three weeks of only moderate bombing by the coalition, Gadhafi’s forces have gotten used to it. Coalition air strikes no longer cause terror and confusion.

A separate but equally important question is: Even if coalition forces increase the intensity and effectiveness of their military operation and, as a result, Gadhafi is forced to step down, who would step in to govern the country? Who would play the role of the “surrogate army?” In Afghanistan, that function was performed by the anti-Taliban alliance of field commanders led by U.S. Green Berets. But with Libya, U.S. and European leaders are still learning the names of rebel leaders and the different tribes opposing Gadhafi, while NATO chiefs still haven’t decided whether they should arm the rebels (and if they have the right under the United Nations Security Council resolution to do so).

Moscow’s position on Libya is once again full of hypocrisy. Moscow abstained during the UN Security Council vote, making it possible to launch the military operation. But as soon as the campaign started to falter, Russian leaders went on the attack, accusing NATO of going beyond the intent of the resolution. Moreover, the Kremlin insists on achieving some form of political decision, pretending not to understand that the longer Gadhafi remains in power, the more civilians will be killed.

My concern is not that NATO is once again being used to defeat a dictatorial regime, but that the Libyan operation will always be inadequate and ineffective as long as there is no political will from the United States and most NATO members to apply the kind of massive military force that is necessary to achieve its goals.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.