The coalition military operation against Libya that began on Saturday should have given Prime Minister Vladimir Putin a compelling reason to support U.S. President Barack Obama. The Libyan operation was a clear illustration of Obama’s consensus-based foreign policy doctrine — one that is anti-Bush at its core and grounded in multilateralism and respect for international institutions. These are key principles that Putin has been urging the United States to adopt ever since the Iraq invasion of 2003.

Putin made his strongest appeal for U.S. multilateralism at his Munich speech in February 2007, in which he sharply criticized — and perhaps rightfully so — the United States and, in particular, the administration of former President George W. Bush for its illegitimate use of military force, unilateralism and disregard for international law and institutions.

Referring to the United States, Putin said in Munich that it was unacceptable to have “one single center of power. One single center of force. One single center of decision making. This is the world of one master, one sovereign.”

A year later, during Obama’s campaign trail debate with Hillary Clinton in Los Angeles in January 2008, it would appear that Putin’s calls were answered. “I want to end the mind-set that got us into the [Iraq] war in the first place,” Obama said.

Indeed, Obama ended that mind-set with, ironically enough, another war — the Libyan military operation. He went out of his way to secure international legitimacy through the Arab League and the United Nations Security Council, which passed Resolution 1973 allowing for “all necessary measures,” except ground forces, to protect Libyan civilians.

Furthermore, he demonstratively took a back seat in Operation Odyssey Dawn, letting France, which launched the first airstrikes on Saturday, and Britain to take the lead. They will handle the detailed enforcement of the no-fly zone, while the United States’ long-term role will be providing logistics and intelligence, according to U.S. officials.

Almost as if to drive the point home that this is not a U.S.-driven operation, Obama left for a five-day trip to Latin America to talk trade while the United States went to war.

To be sure, Obama went out on a limb with his consensus-based policy toward Libya. His conservative critics claim that building the “broad coalition” was too cumbersome and time-consuming. They argue that if Obama had disregarded all of those diplomatic niceties and acted quickly and unilaterally by ordering air attacks in the first week of the Libyan uprising — when the opposition forces had made some key initial advances — Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi’s forces would have probably been defeated in days.

In theory, Putin had every reason to embrace Obama’s international effort to end the carnage in Libya — or at the very least, support Russia’s neutrality on the issue, as President Dmitry Medvedev has done. This time around, there was no Bush-era “coalition of the willing” or mission to export democracy to an Arab state. Objectively speaking, Putin couldn’t have asked for a more legitimate and legal international humanitarian operation.

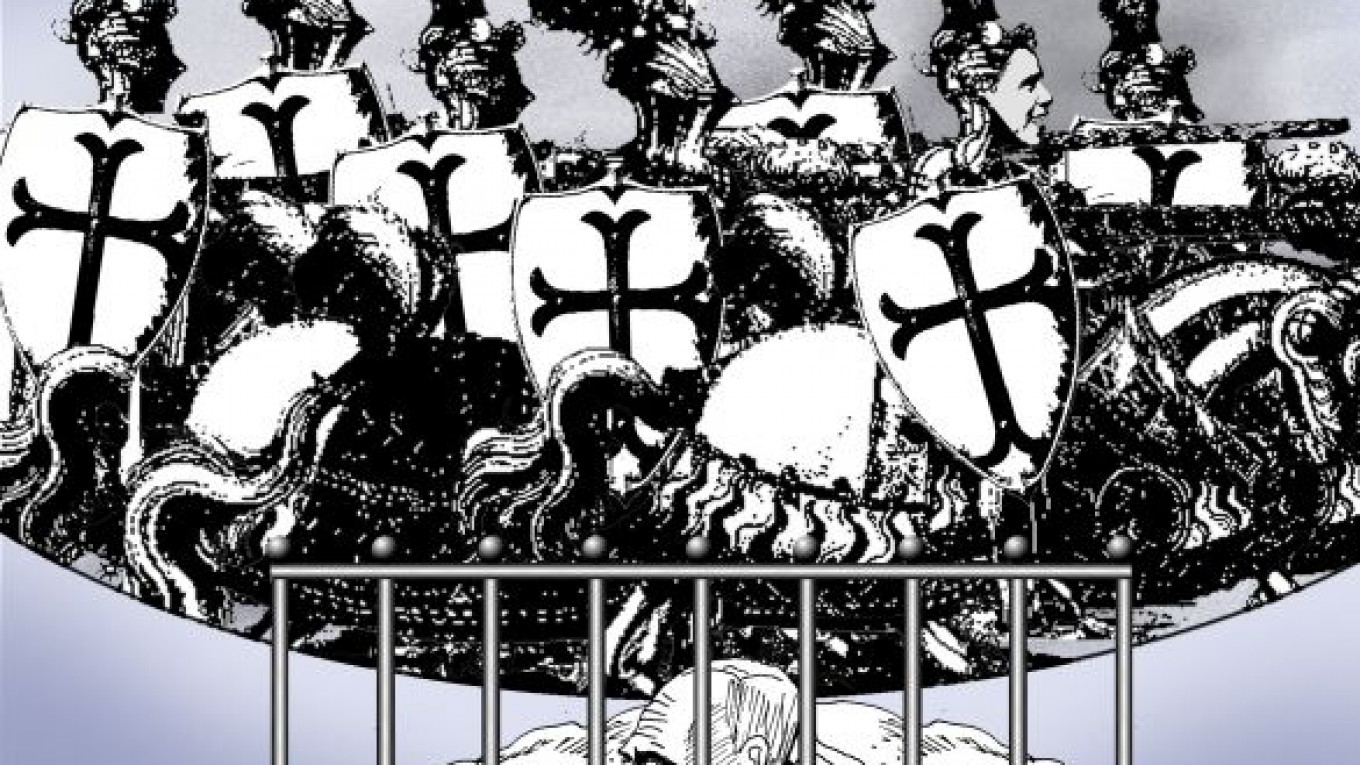

But all of Obama’s multilateralism seems to have been lost on Putin, who has proved over the past decade to be the ultimate naysayer when it comes to U.S. foreign policy, regardless of who is in the White House. On Monday at the Votkinsky factory — an ideal venue given that it produces the Topol-M intercontinental missile — Putin compared the Libyan operation to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and said the intervention “resembles medieval calls for crusades.” Interestingly, Gadhafi has used a similar phrase — “the colonial aggression of crusaders” — to oppose the intervention.

Several hours after Putin’s comment, Medvedev said any comparison to crusades was “unacceptable” and implied that if Russia were truly against the UN resolution, it should have used its veto power in the Security Council to delegitimize the military operation. (Tuesday, Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov, in an apparent attempt to dismiss the impression that the divergence in opinion represents a serious split in the tandem, said Putin was only expressing his personal opinion, not the official government position.)

It would seem that Putin and Obama see eye-to-eye on the future role of the United States in world affairs, and most of Putin’s demands — including U.S. abstention from lecturing Russia and “spreading democracy” in the former Soviet republics, as well as its respect for international organizations — have been met by the Obama administration. This broad common ground should provide the foundation for strengthening U.S.-Russian relations in the political, economic, global security and foreign policy sectors for the long term.

But Putin’s sharp — and, indeed, unacceptable — reaction to the U.S. role in the Libyan intervention once again demonstrates that he is more interested in being a spoiler of reset than its chief supporter. If Putin indeed plans to remain in power until 2024 or even longer, this does not bode well for U.S.-Russian relations.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.