Following last season’s mostly dubious parade of ballet revivals and reconstructions and the disastrous “Creation 2010 …” by French choreographer Angelin Preljocaj, the Bolshoi Theater finally came up late last December with a new evening of ballet worth cheering about — a triple bill, titled “Ballets of the 20th Century,” in which the Bolshoi debut work of contemporary American choreographer William Forsythe, titled “Herman Schmerman,” was framed by George Balanchine’s “Serenade” and “Rubies.” The program is due to return to the Bolshoi this week for the first time since its premiere.

Forsythe is one of the giants among present-day choreographers. Born and trained as a dancer in the United States, he has spent most of his career in Germany, leading Ballett Frankfurt for some two decades and is now director of The Forsythe Company, based in Dresden and Frankfurt, which he founded in 2004.

When his choreography first began to appear three decades ago, Forsythe was hailed as the heir to Balanchine. But that proved to be only partially correct, at most. His ballets are entirely abstract and explore movement to the very extreme of what seems humanly possible. A major objective has been the “deconstruction” of classical ballet, and computer programs have played a significant role in his organizing of dance steps.

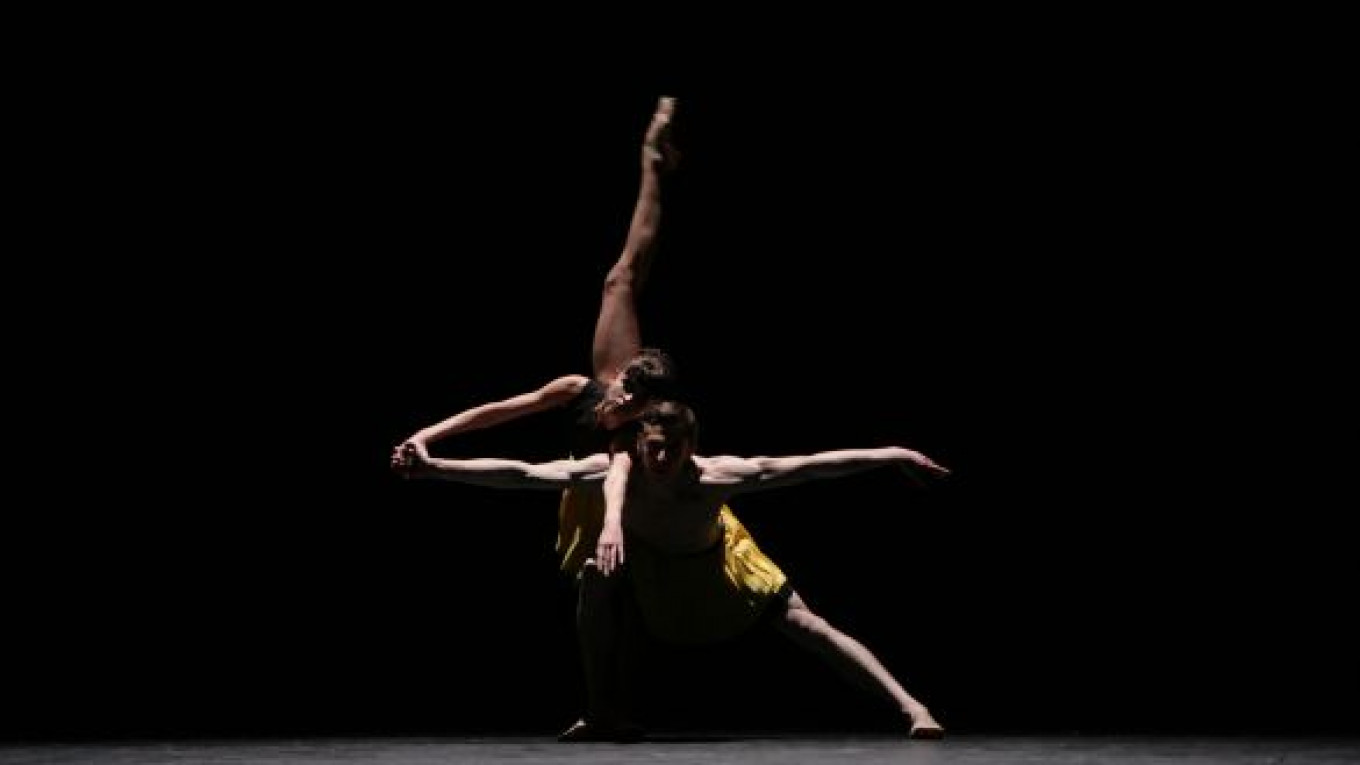

“Herman Schmerman” is a two-part work. The opening quintet was premiered in May 1992 by the New York City Ballet and clearly shows some influence of Balanchine, who founded that company. The second part, a duet between a seemingly competitive male-female pair, was added four months later for performances by Ballett Frankfurt. Though superficially unrelated to each other, the two parts add up to a cohesive and thoroughly exhilarating whole. The electronic music is by Forsythe’s frequent collaborator, Dutch composer Thom Willems; costumes are the joint work of Forsythe and the late Italian designer Gianni Versace.

The ballet’s title has no connection whatsoever to what takes place on stage. “I first heard the phrase ‘Herman Schmerman’ used by Steve Martin in the film ‘Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid,’” the choreographer was quoted as saying at the time of the quintet’s New York premiere. “I think it’s a lovely title that means nothing. The ballet means nothing, too. It’s a piece about dancing that will be a lot of fun. It’s just five talented dancers dancing around — and that’s good, isn’t it?”

The Bolshoi dancers who appeared on opening night did a mostly splendid job in assimilating the elements of what Forsythe calls his “alphabet” of dance. Particularly notable in the quintet was Alexei Matrakhov, still a member of the corps de ballet, who displayed qualities that someday might well lead him to stardom. Another corps de ballet member, Anna Okuneva, together with soloist Denis Savin, gave a thrilling and what seemed completely idiomatic account of the duet.

“Rubies,” set to Igor Stravinsky’s Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra, is the central section of Balanchine’s three-part “Jewels,” created in 1967 for the New York City Ballet. Moscow has previously seen it in some excellent performances by the Mariinsky Theater both as a separate piece and in the context of the complete ballet.

In staging “Rubies” for the Bolshoi, former Balanchine soloist Sandra Jennings largely succeeded in transferring the ballet’s energy and elegance to the theater’s dancers. “Rubies” calls for all-out dancing and loads of charm in the lead female role. And it certainly received both on opening night from the Bolshoi’s wondrous Natalya Osipova, who produced one of the most remarkable displays of virtuosity to be seen at the theater in recent seasons.

The performances of “Serenade,” which opened the triple bill, proved a very happy surprise. As originally staged for the Bolshoi in 2007, what is perhaps Balanchine’s most exquisite work lacked most of the magic I recall from performances by the New York City Ballet in the days when the master himself was still in charge. In its restaging in December by Sandra Jennings, the Bolshoi troupe finally captured at least a large part of that magic, with Balanchine’s characteristic leg, arm and torso movements and the entire atmosphere of the ballet achieving near-authenticity.

On opening night, Yekaterina Krysanova brought to the lead role not only her usual superb technique, but also a degree of pathos I can’t recall ever having seen before in her dancing.

While “Serenade” will play again in April and “Rubies” in July, the performances of “Herman Schmerman” this week appear to be the last on the Bolshoi’s schedule this season. Given the vagaries of Bolshoi programming, it may be quite some time before Forsythe’s astounding choreography makes its way again to the Bolshoi’s stage.

“Ballets of the 20th Century” (Balety XX veka) plays March 3 and 5 at the New Stage of the Bolshoi Theater, located at 1 Teatralnaya Ploshchad. Metro Teatralnaya. Tel. 250-7317, www.bolshoi.ru.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.