On Tuesday, the epic saga surrounding Russia’s purchase of French Mistral-class helicopter carriers ended. On that day, Russia signed an intergovernmental agreement with France on the deal. In many respects, this purchase represents a revolution in thinking at the Defense Ministry. After 50 years of Russia’s military-industrial complex striving for complete self-sufficiency and dictating its own interests to the army, Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov has sent a clear and unequivocal message: The era of its monopoly over the domestic military market has come to an end.

But taking a broad historical view, the Mistral deal is nothing new. Russia has always been an active buyer of weapons from abroad. The country first began purchasing weapons from the West as far back as the 15th century under the reign of Tsar Ivan III, who essentially created the centralized Russian state.

Russia turned to Western military specialists and engineers for assistance and purchased weapons from the West throughout the 16th century, especially under Ivan the Terrible. During the 17th century, Moscow established close ties with Sweden, which was Russia’s main source for cannons and iron. The fact that Sweden was constantly fighting Poland, Russia’s traditional enemy, helped solidify military ties between Moscow and Stockholm.

Peter the Great is the most vivid example of Russia’s deep cooperation with foreign military experts, including the extensive purchase of foreign weapons. This policy played a key role in his military reforms and modernization — above all, creating Russia’s first regular army and navy based on the European model.

There was a new surge of foreign arms purchases 150 years later during the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856, when Russia realized how far its technology lagged behind Europe. Buying weapons from abroad continued until the imperialist regime collapsed in 1917. If you look at composition of the Russian fleet during the 1904-05 war with Japan, practically all of the most effective and modern ships were either purchased abroad or built in Russia according to foreign specifications. With few exceptions, purely Russian-manufactured ships did not earn distinction for their combat or technical characteristics. Arms imports reached a peak after the first three years of World War I, when the Russian defense industry was unable to meet the army’s enormous need for small arms, machine guns, artillery and ammunition.

But purchases of arms and technology from abroad did not stop with the formation of the Soviet Union. From 1922 to the start of World War II, the Soviet Union continued these purchases and was able to create its own defense industry and military production facilities thanks to a large degree to the participation of foreign countries, particularly Germany. In this context, it is worth mentioning the U.S. lend-lease program during World War II, according to which $11.3 billion worth of military equipment was shipped to the Soviet Union.

Even in the post-World War II period, the Soviet Union, having built a largely self-sufficient defense industry, resorted in some exceptional cases to making arms purchases from the West. For example, in the second half of the 1940s, Moscow legally purchased Rolls-Royce Nene II and Derwent jet engines from Britain, along with their licenses. Once the Soviet Union mastered production of those engines, they were installed on almost every major Soviet fighter jet, including the mass-produced MiG-15. Legend has it that famed Soviet aviation designer Artyom Mikoyan won the contract to produce the jets by beating the Rolls-Royce president in a game of pool in 1946. Imported components were even used for strategic systems. In another example, Moscow purchased 3-meter diameter Bridgestone tires from Japan in the early 1980s for use on its MAZ-7904 Tselina mobile rocket system because Soviet industry did not produce that type and size of tire.

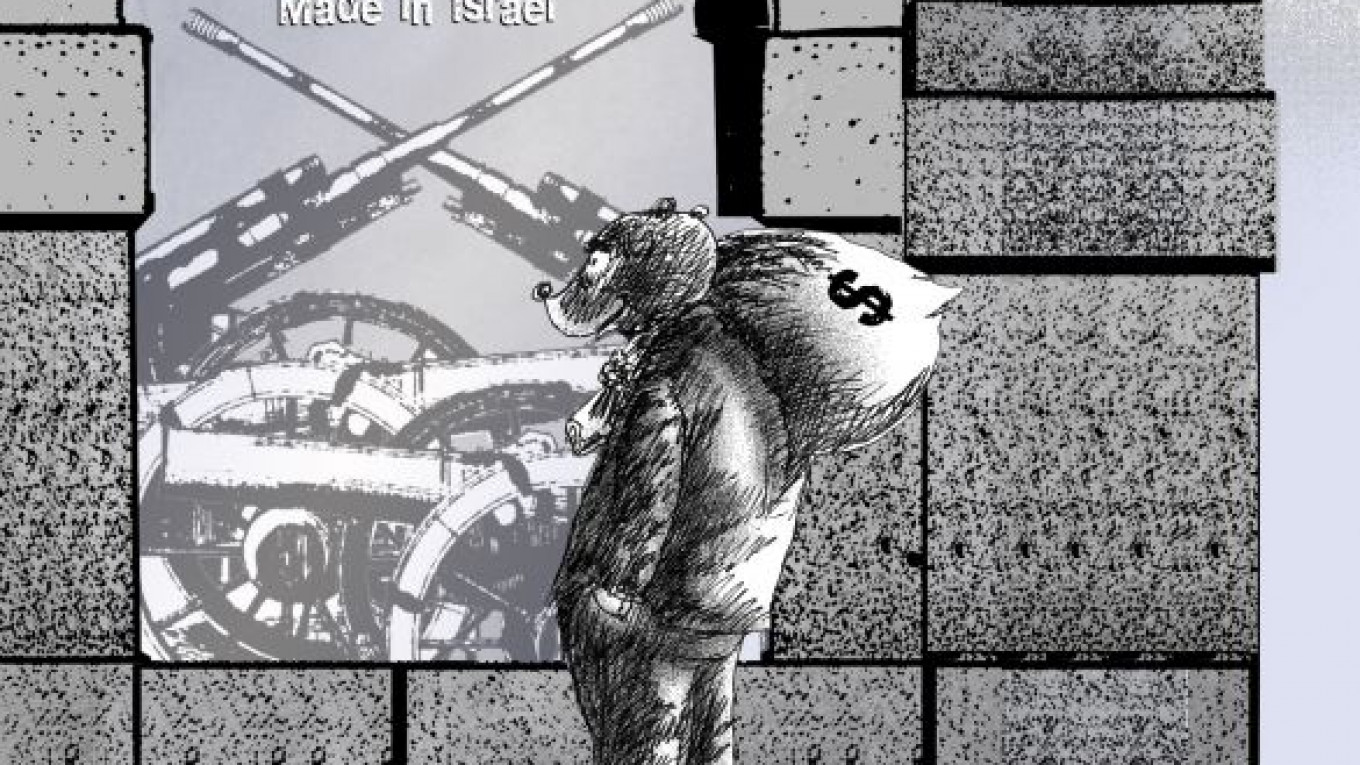

Given the size of the purchase, the Mistral contract is, indeed, a landmark deal. But from a purely military point of view, Russia’s purchases of sniper equipment for use in anti-terrorist operations and the import of Israeli drone aircraft and French inertial navigational systems is more significant because they are much more likely in a real conflict.

Ruslan Pukhov is publisher of the journal Moscow Defense Brief.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.