Ever since 2003, when former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his business partner Platon Lebedev were arrested on fraud and tax evasion charges, prosecutors and Kremlin officials have sworn that the case is not political but purely legal. In 2005, the two were found guilty and sentenced to eight years in prison.

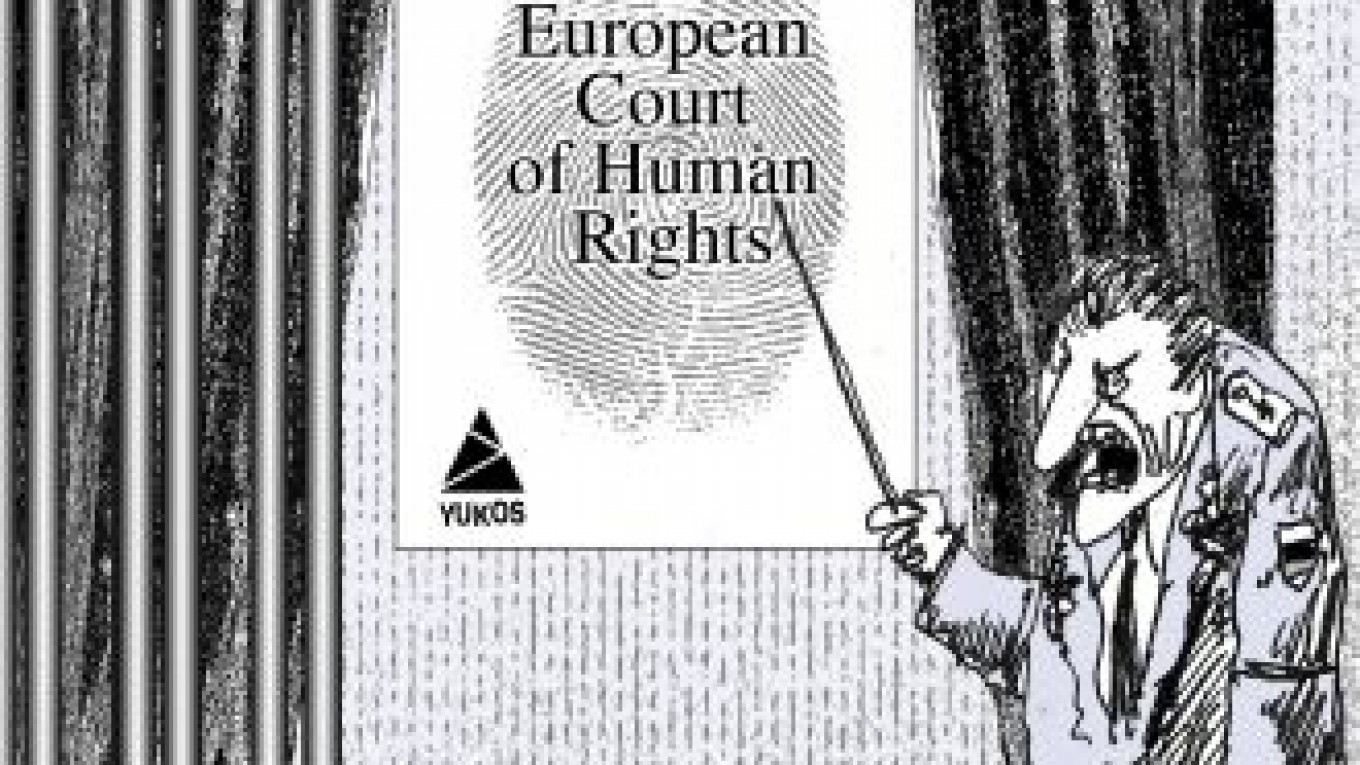

In March 2009, prosecutors filed new charges against Khodorkovsky and Lebedev on the grounds that they purportedly embezzled oil and laundered money. On Friday, prosecutor Valery Lakhtin demanded that Khodorkovsky and Lebedev be jailed for an additional six years in prison after their current eight-year term ends in October 2011. As justification, Lakhtin cited two “aggravating circumstances”: The two defendants “undermined the foundations of the state by putting pressure on the media and filing lawsuits with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.” Unfortunately there are no such aggravating circumstances in the Criminal Code.

Russia officially recognized the right of Russian citizens to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights after Russia became a member of the Council of Europe and signed the European Convention on Human Rights. But judging from the words of the prosecutor, law-abiding citizens shouldn’t dare file an appeal with the Strasbourg court. If they do, they could be charged with “undermining the foundation of the state.”

In 2007, former MMM chairman Sergei Mavrodi was found guilty of bilking 10,000 investors out of 110 million rubles ($4.3 million in 2007), although many put the number of victims in the millions and the fraud figure as several billion rubles. Mavrodi received a prison sentence of only 4 1/2 years for his crimes. Imagine if Khodorkovsky also swindled a few million Russians out of their life savings. Presumably, he would have also received a similar light sentence. But Khodorkovsky’s real “crime” was that he stuck his nose into politics, and for that, the prosecutors believe, he should be locked up for 14 years and serve the same sentences that serial killers and terrorists do.

Lakhtin’s phrase about “undermining the foundations of the state” has no legal meaning whatsoever and should not be admitted as proof of wrongdoing. But it does send a powerful signal to the judge. Perhaps this case against Yukos has been dragged out for as long as it has — more than 18 months — because it is much less predictable than the first trial. As one former official noted, the second case does not have a political manager running the show — a role then-Kremlin deputy chief of staff Igor Sechin played in the first case. What’s more, in their court testimony, current and former ministers have underscored how flimsy the prosecution’s case really is. For example, Industry and Trade Minister Viktor Khristenko, who was a deputy prime minister supervising energy fields from 1999 to 2008, denied any knowledge of large-scale embezzlement at Yukos and suggested that if any oil was missing, state-owned pipeline monopoly Transneft should be held responsible, not Yukos. The prosecutor’s new charges against Khodorkovsky and Lebedev were also placed in doubt by court testimony from former Central Bank chief Viktor Gerashchenko, former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov and former Economic Development and Trade Minister German Gref.

President Dmitry Medvedev has vowed to reform the court system, including measures to liberalize criminal proceedings against defendants charged with financial crimes. How should the court proceed in the case against Khodorkovsky? The prosecutor has given a strong hint: Khodorkovsky is a hardened criminal who refuses to acknowledge his guilt and is an enemy of the state. There are no signs from the Kremlin that it will appeal for leniency or parole for Khodorkovsky. This means that in all likelihood, he will well sit behind bars for at least another six years.

Maxim Glikin is the editor of the political desk at Vedomosti, where this comment appeared.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.