Alexei Balabanov’s latest film “Kochegar,” or “Fireman,” a tale that looks back to the chaotic 1990s, has, like many of his previous films such as “Brat,” sparked debate.

Set in the 1990s, the film follows a shell-shocked veteran of the Soviet Afghan war, who works and lives in a boiler room on the edge of St. Petersburg. Yakut by nationality, the veteran’s main passion is his novel, a cherished never-ending story that he is typing with one finger.

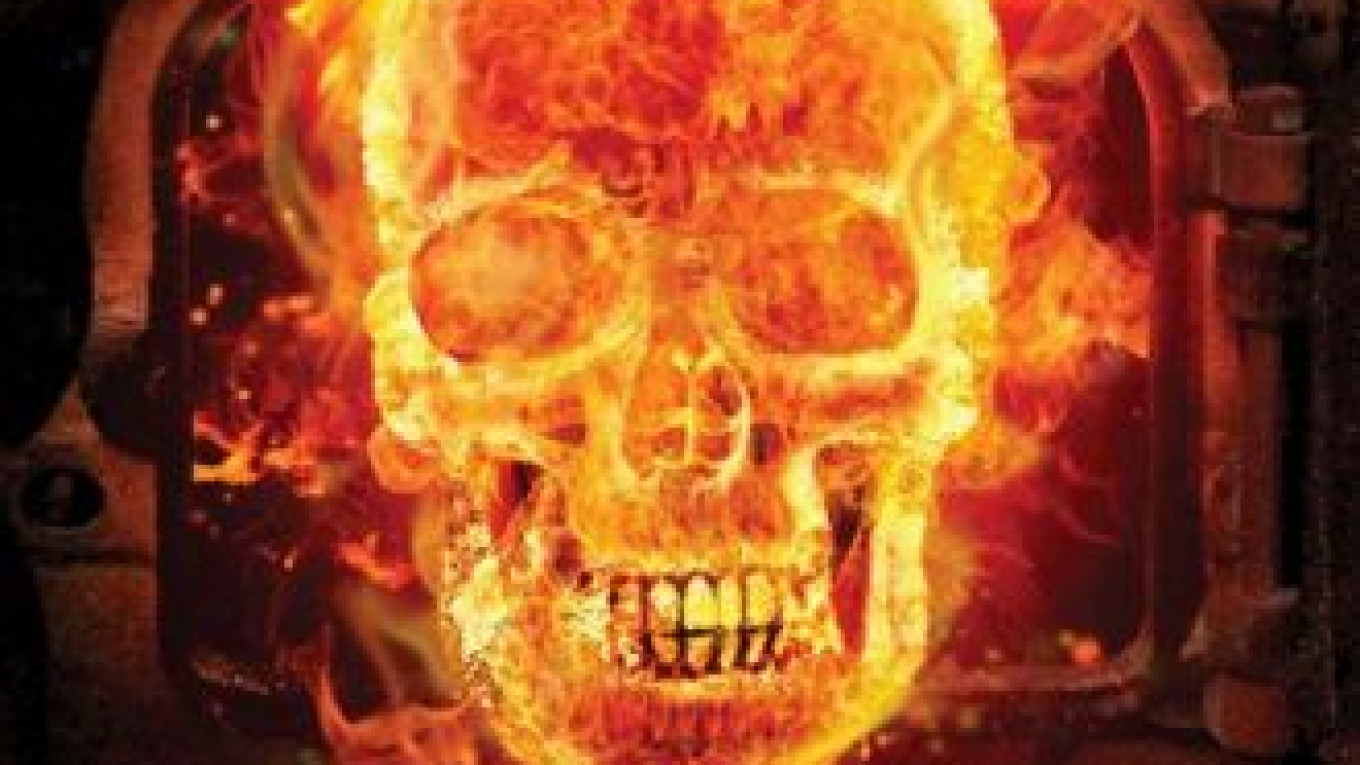

As he types on and on, post-Soviet thugs, with whom the veteran once served in the army, visit his boiler room, hauling in big bags for the fire. It doesn’t take long for the viewer to realize what the bandits are bringing to burn: the bodies of their victims, bad people, the killers say.

Other visitors include two little girls, who come to hear tales and stare into the fire, and the veteran’s daughter, a great debut by model Aida Tumutova, who plays the owner of a fur coat boutique.

She visits to ask for money and also to stare at the fire. Her fate is entwined with the boiler room.

If you have ever seen any Balabanov films of life in the 1990s, such as the two “Brat” — or “Brother” — films and the black comedy/action thriller “Zhmurki,” or “Dead Man’s Bluff,” then the smoking chimney shafts, gray skies, massive snowdrifts and bandits in sweatpants, sunglasses and leather coats will be familiar.

Balabanov, who also wrote the screenplay, has, as ever, memorable dialogue. When the killers visit the veteran, they greet him by asking: “Still writing?” — “Still shooting?” he says in return.

Mikhail Skryabin, a little-known theater actor from the Sakha republic, who played a Vietnamese worker in Balabanov’s grim black comedy “Cargo 200,” this time plays his own nationality, Yakut.

Some critics see the story as a metaphor for Balabanov’s life, with the Yakut representing the director, while others see us — the audience — as the Yakut watching the fire in a boiler room. The mixed reaction — Afisha’s film critic Roman Volobuyev called it Balabanov’s great failure; others say it is one of his best — is not important to Balabanov.

“I personally don’t care what critics think about “Kochegar,” Balabanov said in a telephone interview with The Moscow Times. “Every time one of my movies comes out, I get accused of something new — Russophobia, anti-Semitism, fascism. … I’m sure this time I’ll be blamed for something again. That’s because I’m making films of a different kind.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.