Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, Kremlin first deputy chief of staff Vladislav Surkov and their ideological supporters don’t believe Russians can be trusted to vote. They are not smart or civilized enough to vote responsibly.

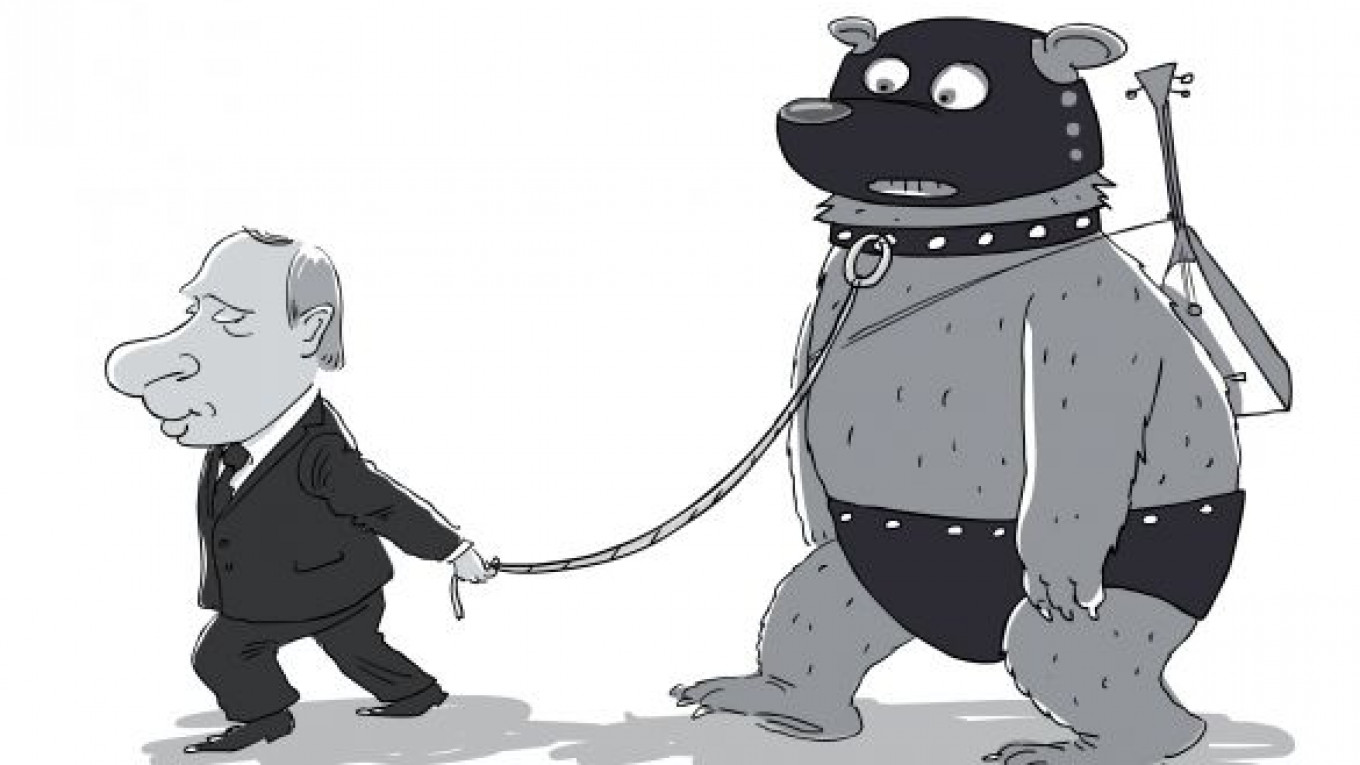

This condescending attitude is by no means limited to voting; they believe the masses are not able to do anything. That is why Russia needs a “benevolent tsar” with an iron-strong vertical power structure to explain to the ignorant masses what is best for the country and how to modernize it and to appoint competent governors and mayors to implement Putin’s wise decisions across the country.

When in 2004 then-President Putin canceled direct gubernatorial elections and gave himself the power to appoint regional leaders, one of his justifications for the decision was that it would somehow help defend the country against terrorism. The other reason he gave was that if the people were allowed to vote, they might elect the “wrong” candidates.

The same arguments have been used for the past 10 years as a justification for squashing political competition. The liberal opposition and human rights activists have been labeled a “fifth column” that is trying — with the financial and organizational assistance of the West — to stage an Orange Revolution to take over the Kremlin.

Since, according to Putin, the liberal and leftist opposition are a radical, revolutionary force, they need to be disqualified from the electoral process through which they could eventually be elected by naive and misguided liberally and democratically oriented citizens. This was the pretext for Putin to disqualify what is referred to as the “nonsystemic opposition” — those parties that refuse to collude with the Kremlin. (The “systemic opposition” — the Liberal Democratic Party, the Communist Party and A Just Russia — are “systemic” precisely because they are part of Putin’s system, obeying his orders and helping the Kremlin create the impression that there are “opposition parties” in the parliament.)

To help the “kind tsar” carry out all his duties, major television channels were placed under government control. In addition, United Russia, with Putin at the head, took control of both the State Duma and Federation Council and made sure its members dominated among governors, mayors and lawmakers in regional legislatures. It’s one thing to increase the number of United Russia members when positions are appointed, but it gets a little trickier to stack the deck in those increasingly fewer cases where candidates for public offices are still elected. As the last series of regional elections showed, this sometimes requires falsifying election returns, but “benign autocracy” can sometimes be messy business. In the end, however, Putin is convinced that the noble ends justify the means.

In short, Putin believes that people are ignorant and can’t be trusted with electing officials. The only exception to this rule, of course, was the presidential votes of 2000 and 2004, in which by some miraculous stroke of fate, the people showed unprecedented wisdom and responsibility when they voted for Putin.

Apart from expressing their open contempt for Russians, Putin and his ideologues also cynically try to package their disdain in pseudo-historical terms — that Russia has its own unique “historical legacy,” which has always been dominated by a strong autocrat in the Kremlin. At the same time, however, Putin allows for the possibility that one day Russians might be able to overcome their 1,000-year legacy, that they will one day become mature and responsible enough to vote. But this will happen sometime in the future, presumably long after Putin retires as leader of the nation.

According to Putin’s and Surkov’s distorted theory of historical determinism, their systematic destruction of the country’s democratic institutions that were built in the 1990s under President Boris Yeltsin were not the result of manipulation, usurpation and abuse of power, but a natural and unavoidable manifestation of Russia’s “predetermined historical path.”

Russia’s own history, as well as the history of other countries, runs contrary to the theory of historical determinism. The “historical determinists” completely ignore Russia’s strong history of liberal reform movements, including those pursued by Alexander II, Nicholas II and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

Putin, Surkov and their ideological supporters cynically use cheap pseudo-historical theories to mask their own usurpation of power and to dismantle the Constitution to preserve their monopoly.

What’s more, Russian and foreign “historians” who reinforce the myth of Russia’s historically predetermined path toward enslavement and authoritarianism make their own intellectual contribution to the continued suppression of human rights in Russia today. They are providing a valuable service to Putin and his cohorts. But they should also remember that each new article or book that promulgates these sham theories leads directly to two main consequences: Russia’s continued backwardness, poverty and enslavement and an increase in Russians who immigrate to the West seeking a free and prosperous life.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.