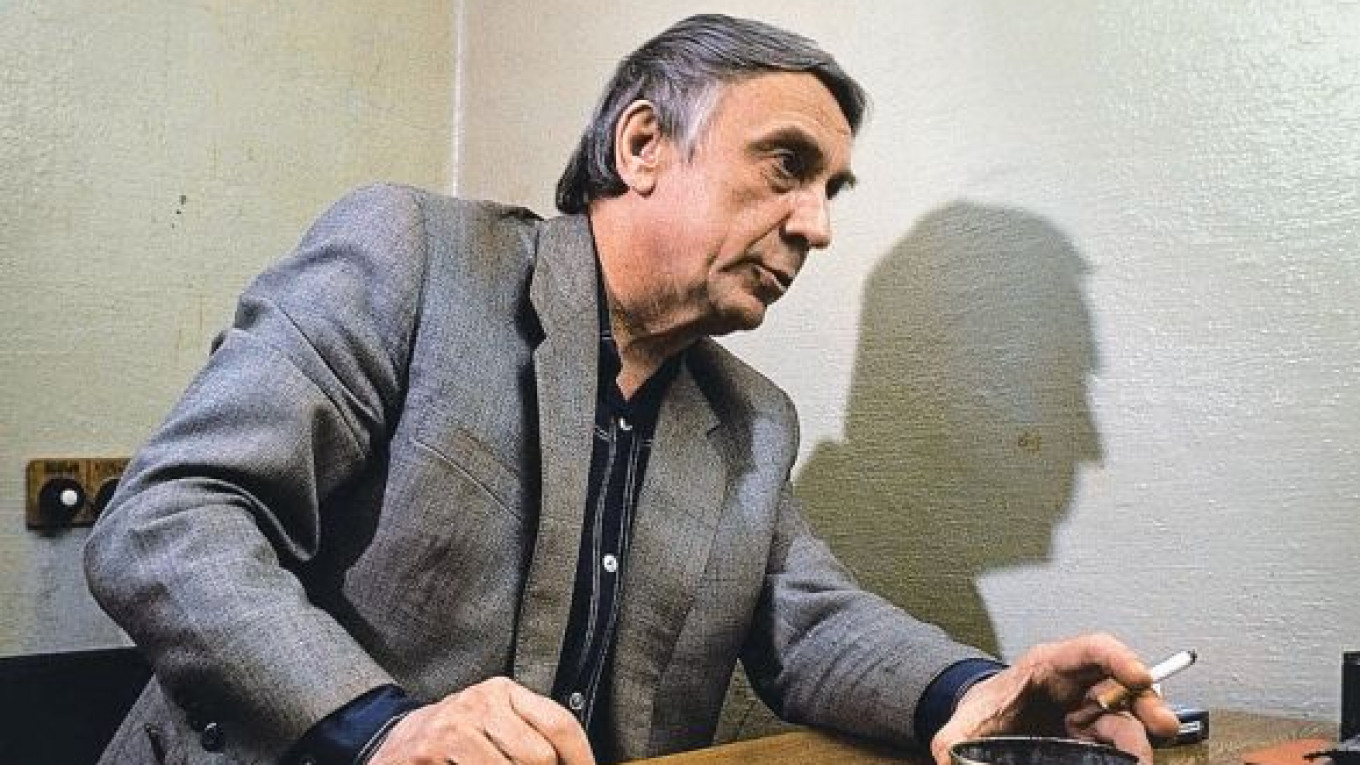

Gennady Yanayev, a leader of the abortive 1991 Soviet coup who briefly declared himself president replacing Mikhail Gorbachev, has died at age 73, the Communist Party announced Friday.

In one of the indelible images of the putsch that hastened the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yanayev's hands shook visibly as he announced that he was taking over as president. Yanayev was later quoted by a newspaper as saying he was drunk when he signed the decree elevating himself from the vice presidency.

A statement from the party said Yanayev died Friday after an unspecified lengthy illness.

He died of lung cancer, television reports said.

The news web site RBK said he died in the Kremlin-run Central Clinical Hospital, citing the Russian International Academy of Tourism, where Yanayev once taught.

Yanayev was one of 12 members of the so-called State Emergency Committee that announced Gorbachev was being replaced on Aug. 19, 1991. Gorbachev was on a short holiday in the Crimea at the time.

Tank divisions rolled into Moscow to enforce the power grab, but crowds of civilians, emboldened by the loosening of strictures under Gorbachev's perestroika policies, turned out to defy them and erected barricades around the parliament building.

The coup collapsed on Aug. 21, but it fatally weakened the already unraveling Soviet Union, which was dissolved four months later.

Yanayev initially said that he was taking over the presidency because Gorbachev "is very tired after all these years, and he will need some time to get better. We hope … he will take office again."

But he and other coup plotters later said they were trying to prevent the breakup of the Soviet Union, many of whose constituent republics were increasingly defying central control.

In 1993, the newspaper Novy Vzglyad quoted Yanayev as saying he was drunk when he signed the decree, but that he denied inebriation affected his judgment.

"My body is such that I remain sane even after drinking all my buddies under the table," he said.

Yanayev and his fellow plotters were arrested and jailed after the coup collapsed, but he and the others were released in 1993 and amnestied by parliament a year later. After his release, he taught history at the tourism academy and was a consultant to the state committee on invalids and veterans of government service.

Yanayev was a conventional creature of the Soviet Union's intricate bureaucracy. His posts included heading the national committee for youth organizations, then moving on to head the national council of trade unions. He became a Politburo member in July 1990 and was appointed to the new post of Soviet vice president that December.

The announcement of his death from the Communist Party took note of those posts and praised him as "a highly professional specialist, … a dear and trustworthy comrade." It made no mention of the attempted coup.

Reports said Yanayev is survived by his wife and two daughters.

An unidentified relative told Interfax on Friday that Yanayev would be buried at the prestigious Troyekurovskoye Cemetery in western Moscow sometime this week. A number of little-known Party bosses are buried in the cemetery alongside notable post-Soviet figures like Andrei Kozlov, a first deputy chairman of the Central Bank who was shot dead in 2006; and two slain corruption-fighting journalists, Anna Politkovskaya of Novaya Gazeta and Dmitry Kholodov of Moskovsky Komsomolets.

(AP, MT)

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.