In December 2000, then-director of the Federal Security Service Nikolai Patrushev proudly described the FSB’s rank and file: “Our best colleagues, the honor and pride of the FSB, don’t do their work for the money,” he said in an interview with Komsomolskaya Pravda. “They all look different, but there is one very special characteristic that unites all these people, and it is a very important quality. It is their sense of service. They are, if you like, our new nobility.”

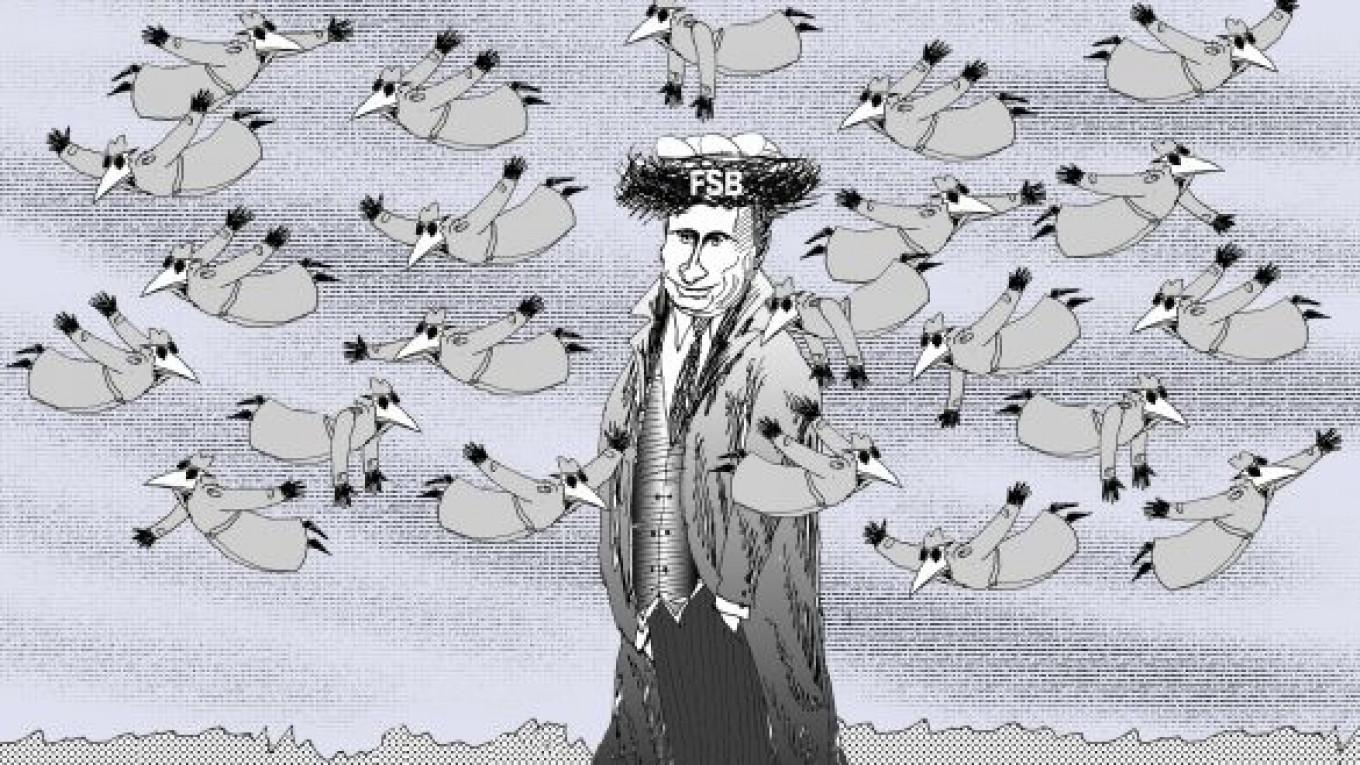

Patrushev hit the nail on the head. Throughout the 2000s, the FSB indeed became the country’s new elite, enjoying expanded responsibilities and immunity from public oversight or parliamentary control. Putin made the FSB the main security agency in Russia, allowing it to absorb much of the former KGB and granting it the right to operate abroad, collect information and carry out special operations.

At the same time, Putin gave the FSB a new and riskier role. As a former KGB officer, Putin viewed the FSB as the only state agency he could trust. He gave the FSB a key responsibility: to protect the stability of the Kremlin’s rule — and, by extension, the stability of the country. In the 2000s, the security services became the main resource of human capital for filling positions in the state apparatus and state-controlled corporations.

Not surprisingly, for many dissidents, journalists and even members of the security service, these changes represent a revival of the Soviet-era KGB. But the reality is more complicated. The KGB was all-powerful, but it was also under the control of the political structure. Throughout the Soviet period, every KGB section, department and division answered to the Communist Party. The hierarchy and subordination was clear. But now, the FSB is impenetrable to outsiders.

As a result, the FSB has evolved into a force that is much more powerful than the KGB. Never before did an officer from the security services lead the country for a decade. By the next presidential election in 2012, Putin will have been at the helm for 12 years. Once he is re-elected — which is all but guaranteed — Putin will rule the country for another 12 years (two presidential terms of six years each). It’s worth noting that former Soviet leader Yury Andropov — the longest-

serving and most popular KGB chief among FSB rank and file — was not a trained KGB agent but a Communist Party apparatchik appointed by the Politburo to oversee state security.

Although the FSB has never tried to change economic rules in Russia, it has significantly changed the country’s political culture. The security services reduced the space available for open discussion of politics and public life. In addition, Russia’s scientific community was intimidated with a series of harsh verdicts against scientists accused of espionage, and the work of nongovernmental organizations was restricted under the false pretense that they were agents of foreign states.

But the powers that Putin has granted to the security services failed to bring the expected results. The FSB invested energy in hunting down foreign spies, but the methods it used raised questions about whether the threat was real or trumped-up. Likewise, the FSB targeted nongovernmental organizations out of fear that such groups might inspire a popular revolution against the Kremlin. This was a clear miscalculation. The organizations in question were too small to be significant threats, did not command widespread support in Russia and did not advocate an uprising against the regime. The security services meddled in politics — perhaps to demonstrate their power and loyalty to the Kremlin — but they clearly misjudged the threat of any opposition to the popular president.

Much more important though, the FSB has miscalculated the nature of the enemy in the war against terrorism. Faced with guerrilla warfare, the security services tried to eliminate a generation of Chechen warlords both within the country and abroad. But when these leaders were wiped out, new ones took their place. Over and over again, the leadership of the FSB blamed terrorist attacks on outsiders, such as al-Qaida and other Arab extremists who infiltrated Chechnya, or foreign intelligence services — including Georgia’s — which purportedly assisted al-Qaida operatives and other insurgents in the North Caucasus. But the focus on external enemies has been misplaced. Arabs were present in Chechnya, but they were always subordinate to Chechens, and the tactics and methods used by terrorists were largely masterminded by former Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev.

Putin opened the door to dozens of security service agents, allowing them to move up in the main institutions of the country. Putin clearly hoped that the large presence of former FSB and KGB agents would prove a vanguard of stability and order for his regime, but once they had tasted the benefits, agents began to struggle among themselves for the spoils.

FSB officers now regard themselves as the only force capable of saving the country from internal and external enemies. They also consider themselves genuine patriots who are saving a nation damaged by the chaos, corruption and servility to the West that marked the 1990s under President Boris Yeltsin. But their mindset has been undeniably shaped by Soviet history. Their excessively suspicious, inward-looking and clannish mentality has translated into weak and ineffective intelligence and counterintelligence operations. In addition, since security agents are everywhere in the government, it also undermines the effectiveness of state governance as a whole.

Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan are co-founders of Agentura.ru. Their book “The New Nobility: The Restoration of Russia’s Security State and the Enduring Legacy of the KGB” will be published in September by PublicAffairs.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.