Russia’s worst drought in a century has turned fresh attention to agriculture’s vital importance for the country’s economy and society. With food prices spiraling and lines for buckwheat growing longer by the day, the authorities are frantically working out schemes to contain inflation and reassure the population that no real food shortages are looming.

But these are short-term measures with short-term consequences. The broader lesson of Russia’s current agricultural woes is that sustainable growth and vitality of the sector will depend on increased investment and accelerated modernization. Will Russia seize the opportunity to become a global agricultural power?

Over the past decade, Russia’s grain sector has made remarkable strides. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia was a net grain importer, Today, it is the third-largest wheat exporter behind the United States and Canada. This dynamic growth was driven initially by falling demand for feed grains as the livestock sector contracted, but starting in the 2000s, the sector benefited from favorable weather patterns and investors who were drawn in by cheap land, higher global grain prices, domestic economic growth and export potential.

The agriculture sector received an additional boost when investors introduced commercial principles and technology to the management of Russia’s farms. Although successor enterprises to Soviet collective farms control most of the arable land, large private agroholdings have been making steady gains and now cultivate about 20 percent of employed land. Foreign investment in Russian agriculture went up from a paltry $156 million in 2005 to $862 million in 2008.

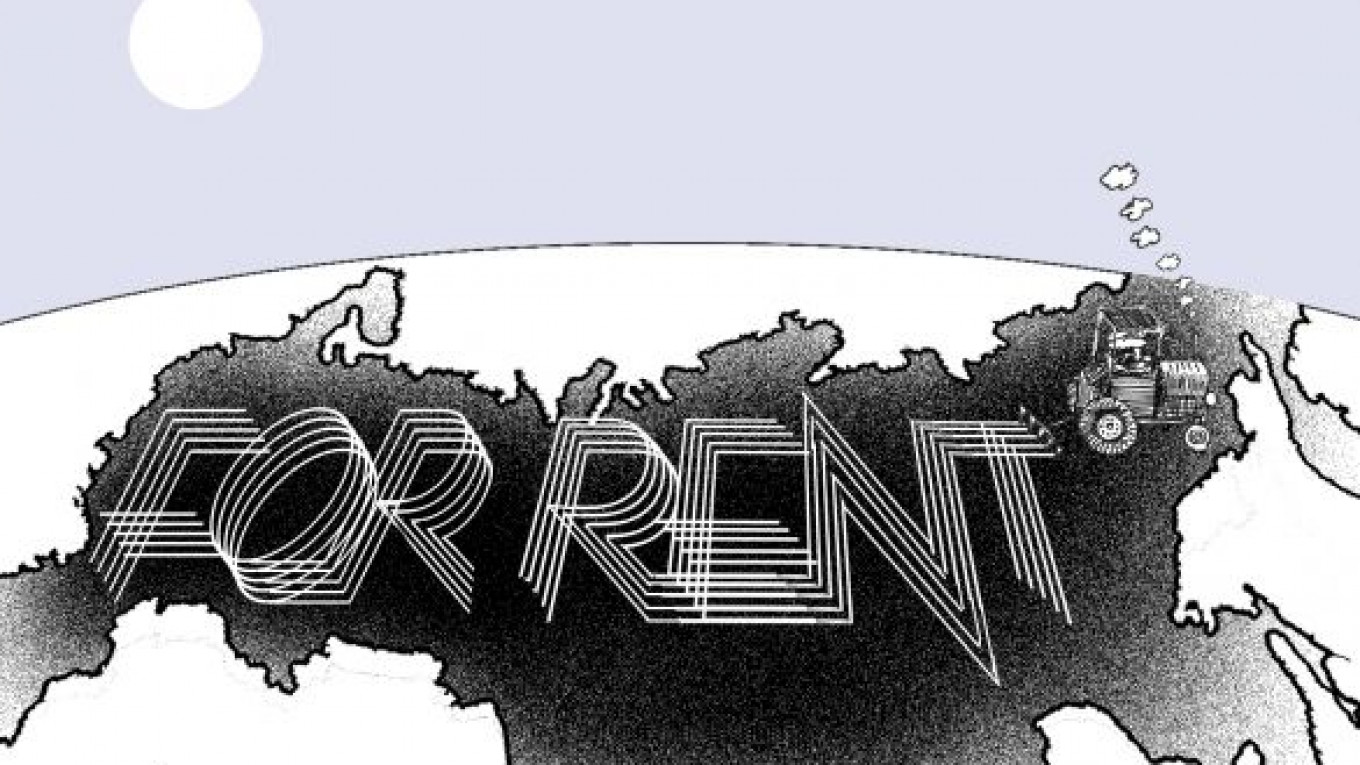

There remains substantial potential for even more investment and productivity increases. Russia has the world’s largest repository of black earth, a soil rich in organic matter that produces strong agricultural yields. According to some estimates, as much as 60 percent, or about 49 million hectares, of Russian black earth is idle. Russia’s total arable land reserves, suitable for cultivation, are even larger. Additionally, grain yields on existing farmland could be increased two to three times with technological modernization. In short, Russia has scope to increase both harvested area as well as efficiency of its yields and to become a global grain-market powerhouse.

In the past, poor infrastructure and transportation networks, as well as complex legal procedures to secure ownership and lease land, were major barriers to attracting private investment in the Russian grain sector. But the drought could potentially open a larger window of opportunity for investors.

In a way, the drought came at a fortunate time for Russia’s agriculture sector. It coincided with a broader government push to attract Western investors to help revamp Russian industries to modernize and diversify the national economy. The extreme weather exposed the dire need for modern technology and equipment on farms and the necessity of massive investments in infrastructure for storage, transport and loading of grains for export. Deputy Agriculture Minister Alexander Petrikov said as much during the Moscow forum on the future of Russian agriculture held last week, indicating that the government must attract foreign investment, technologies and cooperation if it hopes to raise productivity and efficiency on the farm. The political context for increasing the productivity and quality of Russian agriculture was set, most recently, by President Dmitry Medvedev’s approval in February of a national food security doctrine, which sets minimum self-sufficiency production goals as well as quality targets in all main food production categories.

But, of course, not all of Russia’s pastures are green. While, the government’s stated goals and pressing needs present real opportunities for foreign investment, the political and social significance of the agricultural sector heightens the potential for government intervention. As foreign investors in Russia are all too aware, there is a perennial conflict within the country’s political elite on how to balance the need for foreign investment and outside technology with an impulse to maximize state control over sectors that carry outsized economic or social significance. This is precisely what happened at the very heart of Russia’s economy, the oil sector, where the reassertion of state control impeded investment and technology transfers that could have increased production in the long run.

In agriculture, investors are faced with the possibility that the government may one day move to tighten restrictions on foreign cultivation of land. The government prevents foreign investors from owning land, although they have been able to lease arable land, citing national security concerns and the social importance of agriculture to the nation. Moscow’s challenge now is not only to convince investors that transportation systems and export terminals will continue to be revamped and built and that the lengthy bureaucratic process to secure arable land will be worth the investment. To attract broad interest and substantial investments, the Kremlin must also convince private businesses that their investments in Russia’s agricultural sector won’t come under attack from the government.

Unless these assurances are firm and credible, Russia’s promising agricultural future may wither on the vine.

Jenia Ustinova is an associate specializing in agriculture at New York-based Eurasia Group.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.