For over a month, Moscow has been boiling in heat that has approached and sometimes surpassed 40 degrees Celsius, along with heavy, sticky, eye-burning smog. Carbon monoxide levels have reached crisis levels, at six times the maximum acceptable concentration. Other toxic substances in Moscow’s air are at nine times the normal level.

In early August, a journalist called the office of Mayor Yury Luzhkov, seeking comments on the situation. “The office is closed,” a woman at the press office answered, adding that smog had gotten inside the mayoral building, which is located several hundred meters from the Kremlin, so everyone was ordered to go home. This was a weekday, shortly after lunch. “Is it at all possible to get a comment from Mayor Luzhkov?” the reporter asked. “He is not in Moscow,” the woman replied.

Indeed, there are reports that the mayor’s spokesman had been telling journalists that there is no reason for the mayor to return to Moscow. “Why should he?” said the spokesman. “Is there a crisis in Moscow? No, there is no crisis.”

At the same time, a doctor from a local hospital was writing on his blog: “It is a disaster. There is no air conditioning in the hospital, no ventilators working; smog is penetrating everywhere, including the emergency rooms. Each day, 16 to 17 people die. The morgue is full, and there are not enough refrigerators for the dead. They just put bodies along the walls.”

Indeed, according to the Moscow city health department, the death rate has doubled over the past few weeks. And yet Moscow’s mayor chose to remain on vacation in Europe throughout the worst days of the heat and smog.

What would have happened if Luzhkov served in a country that had popular elections for governors? If Luzhkov knew that he would soon be facing re-election — his term expires in October 2011 — would he have allowed himself a vacation while Moscow was being ravaged by heat and toxic smog? Of course not. But neither Luzhkov nor whoever may replace him must worry about voter approval since the Kremlin appoints governors. (Although Luzhkov’s official title is mayor, the city of Moscow, along with St. Petersburg, is designated in the Constitution as a “federal jurisdiction,” and thus Luzhkov was appointed by the federal government on the same terms and conditions as the country’s governors.)

Another example of this is the Nizhny Novgorod region, just 400 kilometers east of Moscow, which has been hit hard by the heat wave and fires. At least 36 people, including seven children, have lost their lives in the region, and more than 1,000 people have lost their homes and livelihoods.

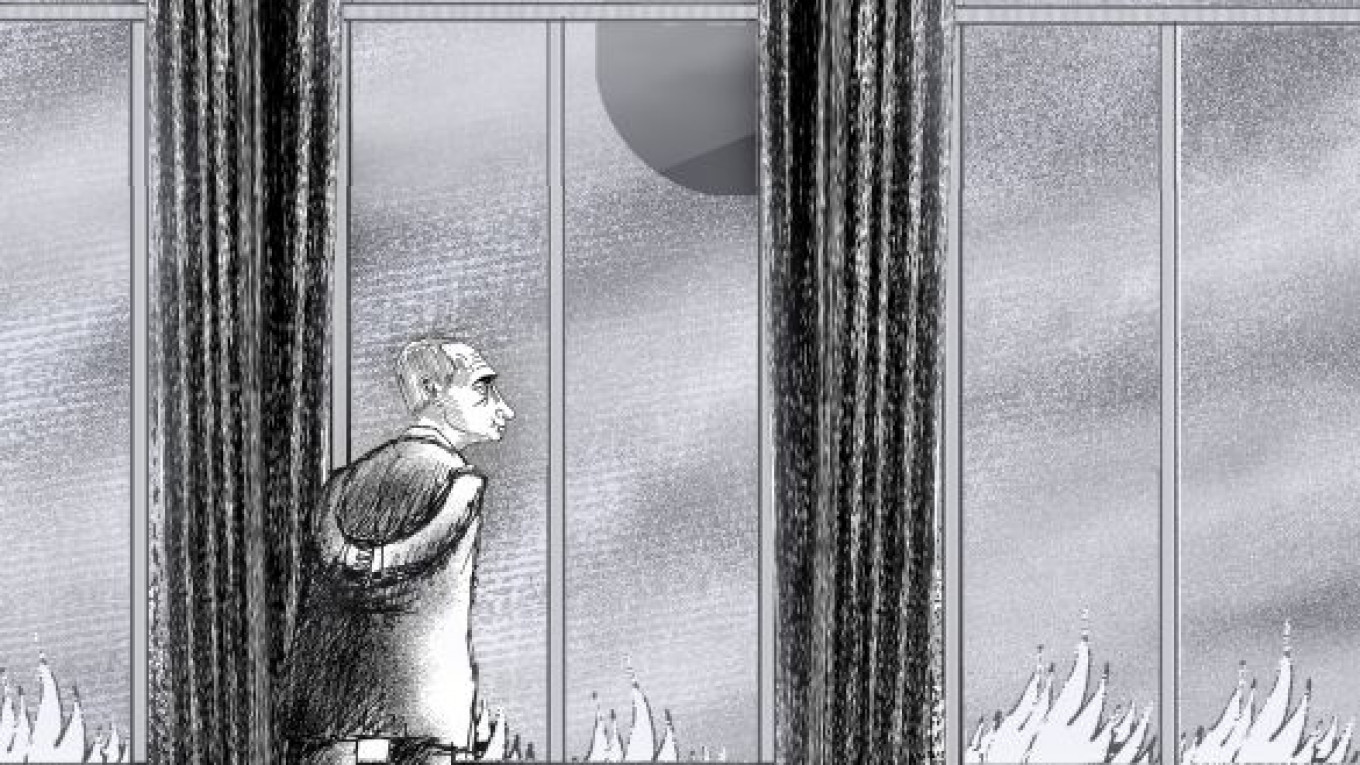

Rare candid footage of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, displayed on government channels, depicted him visiting Verkhnyaya Vereya, a village in the region. People who had lost their homes, clothing and everything else were complaining to Putin that the regional and local governments did not warn them that the fire was coming. There were practically no firetrucks. In many towns and villages, there was no electricity, so water pumps were not operable. “No one even tried to save us,” they wailed to Putin, who was accompanied by Nizhny Novgorod Governor Valery Shantsev.

A week later, an inauguration ceremony officially began Shantsev’s second term in office. Like all other Russian governors, he was not elected by those who live in his region. (Before being appointed governor, he was Luzhkov’s deputy.) He was appointed by the president and thus bears no accountability whatsoever to those he is supposed to serve.

Forestry specialists blame a carelessly enacted Forest Code in 2007 that cut 90 percent of the country’s forest guards. The law was proposed by the government and was quickly passed by the State Duma. The legislation was passed without any discussion or debate within the Duma, without hearings or testimony from outside experts. Russians are now paying the price for Putin’s top-down,

rubber-stamp lawmaking process.

Russia’s burning summer of 2010 underscores something that political scientists everywhere acknowledge. Authoritarian regimes, owing to their lack of accountability, are dreadful at coping with anomalous situations. By controlling the mass media, the leaders in such counties lack the ability to envisage and calculate possible risks.

Unfortunately, ordinary Russians have yet to connect the dots. The tragic situation in which they find themselves stems directly from how they voted in the past. The political apathy that characterizes today’s Russia presents a serious challenge to the country’s survival.

But it seems that this apathy is beginning to lift. The burning summer of 2010 may help Russians understand that their very existence depends on whether the authorities can provide assistance in times of emergency. A regime that cannot respond to its citizens’ basic needs has no legitimacy at all.

Yevgenia Albats is professor of political science at the Higher School of Economics and editor of The New Times magazine. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.