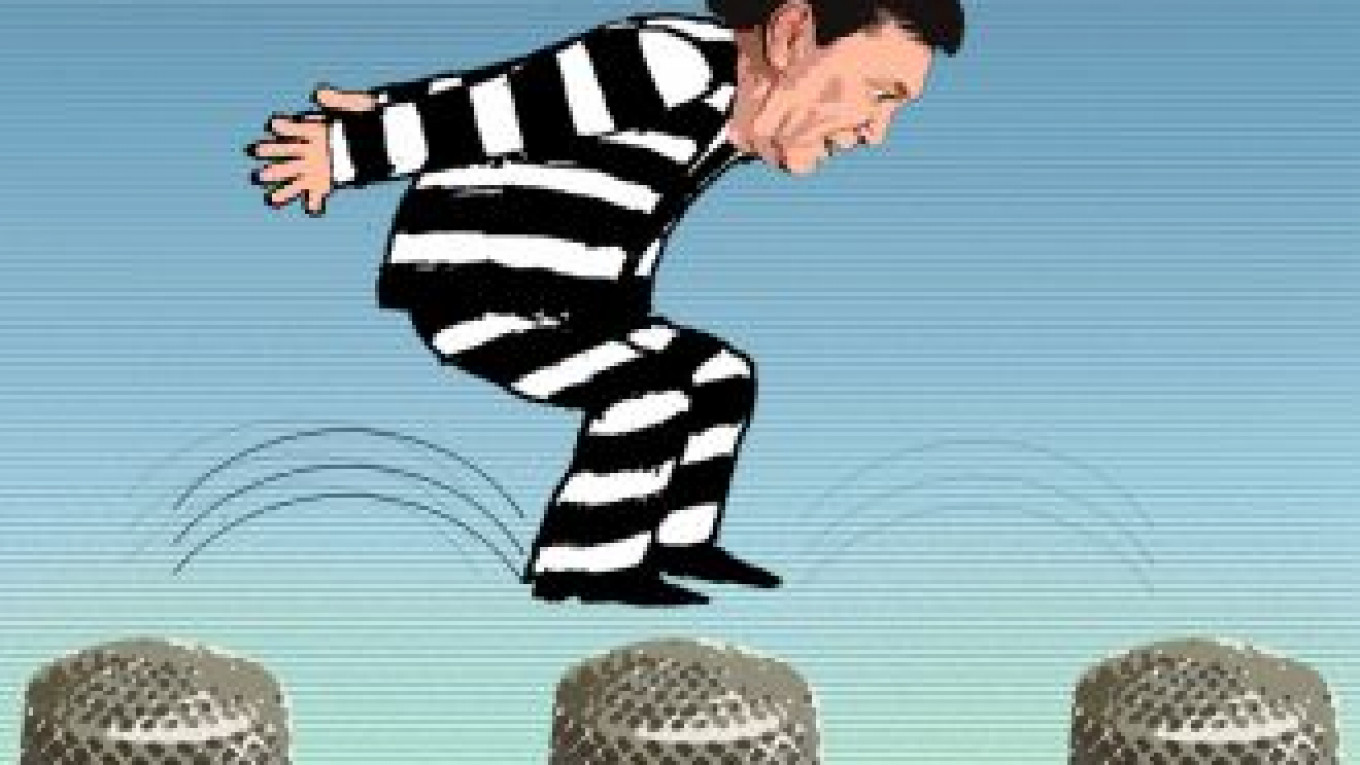

When President Vladimir Putin came to power 13 years ago, we often heard the ?remark, "Once a spy, always a spy." But this might also apply to Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych — with a slight rephrasing: "Once a swindler, always a swindler."

Yanukovych earned the sordid reputation of a criminal after he was convicted twice in Soviet times. He received a three-year prison sentence, for which he served seven months, after committing robbery when he was 17. Three years later, he received a two-year sentence on assault charges.

Yanukovych is also believed to be an academic swindler. He has been accused of plagiarizing 23 publications, including a book that was published in 2011.

Yanukovych has been linked to electoral, academic and financial swindling. He also swindled Ukrainians by reneging on his promise to take the country down a more democratic, European path.

What's more, he is an electoral swindler. In the first round of the Ukrainian presidential election in November 2004, official results showed that Yanukovych defeated his rival Viktor Yushchenko. But international monitors and members of Yushchenko's camp claimed that Yanukovych had committed mass electoral fraud, including corruption, voter intimidation and vote falsification. Many indignant Ukrainians agreed, and hundreds of thousands of them protested during the Orange Revolution against Yanukovych's fraudulent victory. On these grounds, the Supreme Court annulled the second round of the election in December 2004, and Yanukovych went on to lose the vote in the third round.

The 2010 presidential election, in which ?Yanukovych defeated former Prime Minister Yulia ?Tymoshenko, was considered more free and fair than the 2004 vote. But Yanukovych has maintained his role as swindler during his first three years in office. In October 2011, Tymoshenko was sentenced to seven years in prison on charges of abuse of power and embezzlement in a politically tainted case that was clearly driven by Yanukovych's desire to sideline his chief political opponent.

Then there is the financial swindling. Through murky transactions involving Vienna- and ?London-based shell companies, Yanukovych ?reportedly has been able to privatize a huge luxury estate called Mezhgorye, which was previously state property. As it turns out, Yanukovych, despite his public stance against European trade integration, appears to be quite integrated into Europe when it comes to his personal financial transactions and enrichment.

In addition to the Mezhgorye scandal, Yanukovych's first three years in office have been marked by rampant corruption and cronyism that favors loyal oligarchs and his relatives, who have become amazingly wealthy in the short time that Yanukovych has been in power.

Finally, there is Yanukovych's internal political swindling. As president, Yanukovych promised Ukrainians that he would increase political and economic ties with the European Union — including securing an eased visa regime with EU countries, something particularly valued by Ukrainians. But he duped voters on Nov. 21 by announcing he would not sign the Association Agreement in Vilnius after five years of tough negotiations on the huge trade package.

Yanukovych has clearly shown throughout his three years in office that he prefers Putin's brand of authoritarianism and crony capitalism. This has infuriated many Ukrainian voters, who had hoped that he would fulfill his promise and lead the country down a European, democratic path that would raise their standard of living.

According to a recent poll conducted by GfK Ukraine, 45 percent of Ukrainians, including those from the pro-Russian eastern part of the country, prefer closer economic and political ties to the EU, while only 14 percent want closer ties with Russia.

This poll suggests that the majority of Ukrainians reject Putin's vertical power structure — an a?utocratic model that limits civil society and democratic rights and whose kleptocratic state capitalism is a guaranteed path toward long-term stagnation and low standards of living. Instead, Ukrainians want to embrace a European political and economic model based on rule of law, a transparent and accountable government, human rights, independent courts, and institutional checks and balances.

This is one reason why Putin was so adamant that Yanukovych reject the EU agreement. If Yanukovych publicly endorsed the European model by signing the Association Agreement, it would be a strong vote of no confidence in Putin's autocratic model. This would not be lost on millions of Russians. A commitment toward making Ukraine more European could spark calls among Russians, including many Putin supporters, to take similar measures at home, thus undermining the foundation of Putin's own political swindle — that Russia is a stable, prosperous and powerful Eurasian power.

Meanwhile, Putin has downplayed the homegrown nature of Ukrainian protests against Yanukovych by accusing "outside forces" of playing a role. Alexei Pushkov, head of the State Duma's International Affairs Committee, chimed in, writing in comments published on United Russia's website that the Ukrainian protesters were "attempting to repeat the 2004 Maidan scenario with support of sponsors from Europe and the U.S."

Like Putin and other autocrats, Yanukovych is out of touch with a public opinion that is sharply against him. Or perhaps he believes that he can simply ignore his dwindling popularity ratings because he thinks that the army and riot police are on his side. He probably also believes that Ukrainian protesters were paid by the U.S. State Department to hit the streets, an accusation that Putin voiced after thousands of people protested in Moscow after fraud-tinged State Duma elections in December 2011.

Imelda Marcos — wife of former Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos, who built a personal fortune from funds embezzled from the state treasury during his 21 years as the country's autocratic leader — once said, "The fight for survival justifies swindling."

Yanukovych, whose popularity rating has dropped to 19 percent, should find a better way of fighting for his political survival.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.