State oil major Rosneft recently announced that it would buy the gas assets of state diamond monopoly Alrosa in East Siberia. This fairly routine event carries a lot of symbolism. It continues a major trend along with the recent official completion of the $55 billion takeover of TNK-BP by Rosneft.

Through its stakes in Rosneft and Gazpromneft, the oil arm of Gazprom, the Russian government now controls more than 50 percent of national oil production. This comes in addition to its control of about 80 percent of gas production through Gazprom.

Rosneft is more responsible than ever before for maintaining oil production levels and filling state coffers.

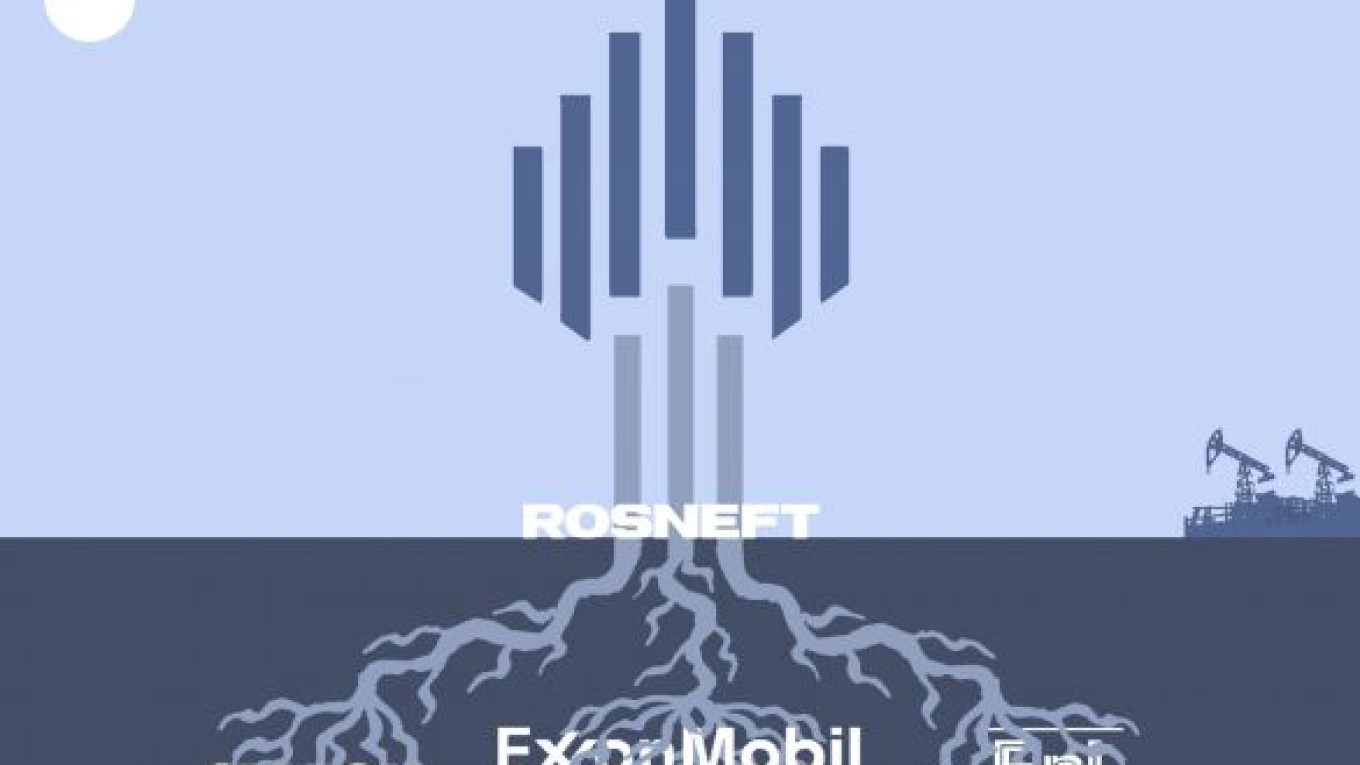

Apart from the political and macroeconomic significance of this consolidation, the development is also associated with some crucial structural changes in the hydrocarbon industry. Rosneft now dominates the Russian oil sector with unrivaled cumulative production of 4.25 million barrels of oil a day. Furthermore, as a result of the acquisition of TNK-BP, it became the world's second-largest oil producer after Saudi Aramco and the largest among listed oil companies. That completes a process of industry consolidation led by the Russian government that started 10 years ago with the absorption of Yukos and Sibneft into Rosneft and Gazprom, respectively.

While the Russian government is now firmly in control of the commanding heights of the industry, that is not leading to an overall demise of the role of foreign companies in the hydrocarbon sector, contrary to what one might expect. Judging by the deal flow, alliances with foreign companies are actually on the increase. In less than two years, U.S.-based ExxonMobil, Norwegian Statoil and Italian Eni have formed a number of joint ventures with Rosneft in the offshore areas of the Arctic basin, the Black Sea and the Far East. Those joint venture blocks have immense combined resource potential, estimated by Rosneft at 280 billion barrels of oil equivalent. However, almost all of those resources are yet to be proven as commercial reserves. In addition, in exchange for its share in TNK-BP, BP increased its stake in Rosneft from 1.25 percent to 19.75 percent and gained board representation. That may potentially offer BP growth opportunities in an alliance with Rosneft both onshore and offshore.

As the saying goes, "With great power comes great responsibility." With all the advantages of having preferential access to exploration plays and infrastructure, Rosneft is now more responsible than ever before for maintaining oil production levels and filling government coffers. Such responsibility comes at a difficult time for Rosneft as it is enters a new phase of exploration while sitting on a mountain of debt. Both renewing reserves and maintaining production levels will rely on greenfield exploration in frontier areas, specifically, the Arctic offshore where costs are high and technological tasks are extremely challenging. In the short and medium term, Rosneft's capacity to explore these new opportunities will largely depend on its ability to manage its enormous debt, which increased from $17 billion at the end of 2012 to an estimated $60 billion after the acquisition of TNK-BP. In the longer run, Rosneft's success in frontier areas will depend on how it manages to integrate and run such a massive business and, specifically, how it manages exploration risks.

Rosneft, incidentally, got a huge break on its debt when it announced Friday that it had signed a $270 billion deal to double oil shipments to China, with $60 billion to $70 billion in an upfront pre-payment.

Still, the problem for Rosneft and its main shareholder, the Russian government, is that the industry track record is generally not on the side of the chosen model. Privately owned oil companies (or, as one might argue, any privately owned companies for that matter) tend to be more efficient than government-owned companies. That is reflected, for example, in the market capitalization of listed state-controlled companies, which are lagging behind when compared on a per barrel of production level with that of private companies. The only way around the inefficiency trap haunting state oil companies is a symbiosis with international companies. This would allow national companies to partially compensate for the lack of competition and gain access to a pool of international human resources which are crucial for the industry.

The best example is Malaysia's Petronas, which is entirely state owned and for decades has relied on alliances with foreign companies to effectively run the Malaysian oil and gas sector and rapidly grow its business both domestically and overseas. International alliances have allowed Malaysia to keep an edge in the global market by, for example, becoming a leading exporter of liquefied natural gas — something that Russia still has to accomplish.

It is therefore not a coincidence that in all its new ventures in the Arctic offshore and also in heavy oil Rosneft now has a foreign partner — either ExxonMobil, Eni or Statoil. The new partners will be financing exploration costs in their respective joint ventures. Rosneft hopes that it should help it to pay back its debt while it maintains an ambitious exploration program. On a strategic level, if done properly, it could allow Rosneft to tap into foreign companies' expertise in managing exploration risks and bringing complex projects onstream. Whether such a private-public partnership can be sustained to the mutual benefit of the partners remains to be seen. Its outcome will play a big role in determining the future of Russia's hydrocarbon industry and its overall petro-state economic model.

Peter Kaznacheev is a consultant and a research fellow in energy and natural resources at the Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.