Russia's irreligious society is preparing for the end of the world.

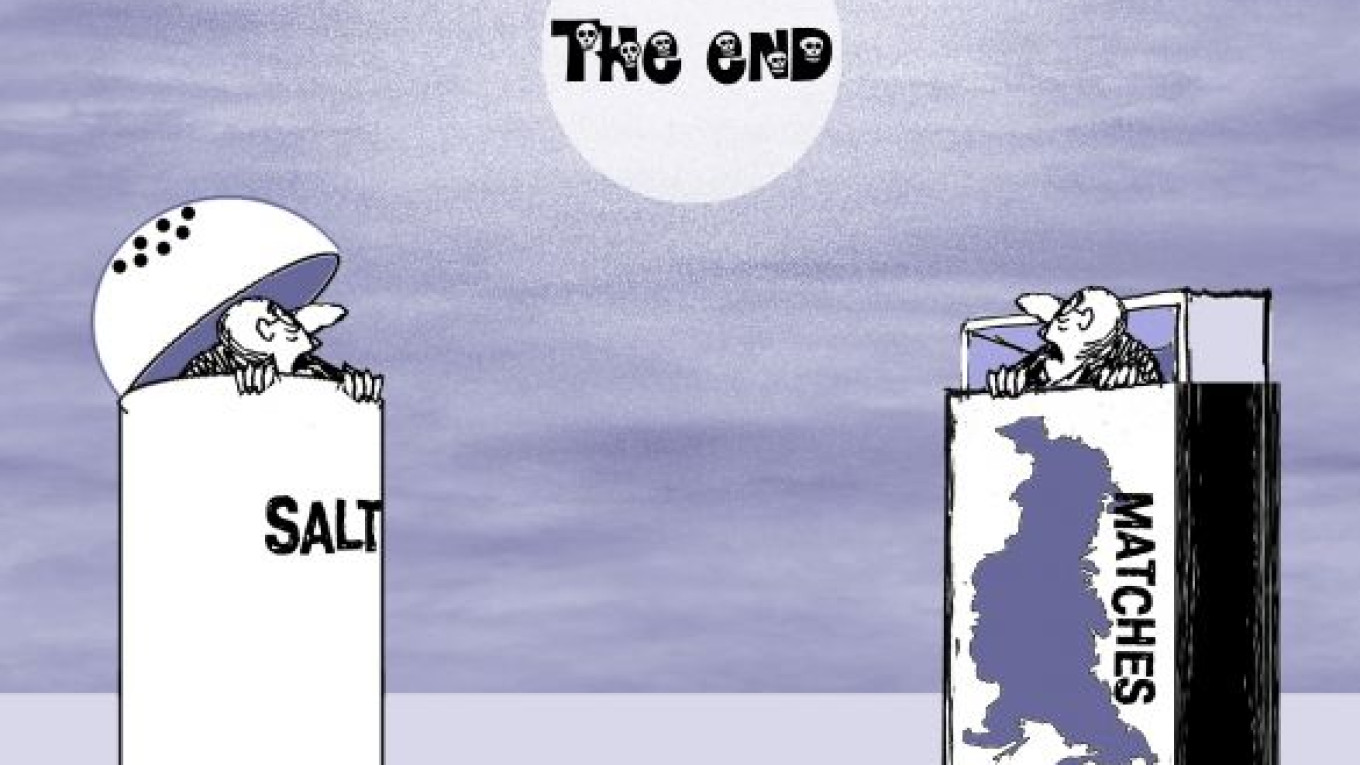

People in the provinces have been buying up salt, matches, candles and canned goods in hopes of riding out the impending catastrophe. In reality, though, the upcoming "end of the world" is just one more in a long line of social and economic disasters that the current generation of Russians has experienced in its tortured history.

The end of the world is supposed to occur very soon, on Dec. 21, which is supposedly the last day of the Mayan calendar. A number of psychics, spiritualists and journalists have found countless creative takes on this date, but only in Russia do they find such a receptive audience.

In Barnaul, many residents are feverishly buying up candles, matches, flashlights and thermoses. In Omutninsk, a town in the Kirov region, panic broke out after a local newspaper published an article titled "Prophecies of a Tibetan Monk." In the city of Novokuznetsk, in the Kemerovo region, people quickly bought up salt from the store shelves. One local resident even wrote a letter to City Hall expressing concern that the authorities were inadequately prepared to cope with the consequences of the impending disaster, such as electrical blackouts and looting in the streets. "Maybe we can get through this disaster with minimal losses if we do our best to prepare for it," the author wrote.

It got so bad that the country's chief health official, the emergency situations minister and State Duma deputies had to officially announce that there would be no doomsday and that there was no reason to be alarmed. They also urged state--controlled television not to frighten people with coverage of the apocalyptic predictions.

Russia is certainly not the only country to fall victim to mass psychosis. It happens in the enlightened West as well. For example, following the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, many U.S. citizens built fallout shelters in their backyards, and schools taught children how to duck and cover in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack. But that relatively short period of mass paranoia seems like ancient history for Americans today. Even during Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney's? campaign, there was no public discussion of the Mormon prophecy contending that Jesus Christ would return after a Mormon was elected president. The average American hoards salt and matches only in the face of a real threat of disaster, such as a hurricane or tornado.

Surveys indicate that 80 percent of Russian Orthodox believers are worried over the implications of the Mayan calendar, which few have ever seen or fully understand. If Russians were more religious, they would prepare for the supposed end of the world in a completely different manner — for example, frequenting the sacraments, praying or paying off debts. But the religious doctrine concerning the punishment of sin has not penetrated the consciousness of most Russians who consider themselves Orthodox believers. This might explain why they have behaved so irrationally as they look for ways to survive the imminent doomsday.

This mindset is unquestionably a consequence of the many social and economic hardships that Soviet and Russian citizens endured in the 20th century. Nearly every Russian over 30 has experienced at one point or another repression, a shortage of foodstuffs and other goods and the country's collapse in 1991. At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, people went months, sometimes years, living in a state of complete uncertainty about the future. The current belief that the end of the world is at hand emerges from a fertile ground of years of political and economic instability and crises.

Sociologists, historians and others often speak of? the "unique Russian ability" to adapt to the toughest conditions. There is something to this notion. Adaptability is definitely one of Russians' greatest resources — a "competitive edge," if you will. How many times have we heard someone say, "Our standard of living isn't bad at present, but if we had to, we could get by on bread and water somehow"? But that strength has a destructive flip side: passivity in civil and political affairs, fatalism and the firm belief that the country is doomed to be unstable and crisis-ridden.

That ability might be good for braving the end of the world, but it's terrible for leading a normal life. While Americans prepare for very real disasters, Russians prepare for a vague and improbable cataclysm using the only method they know: stocking up on matches and salt — and hoping that luck will get them through it all.

This comment appeared as an editorial in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.