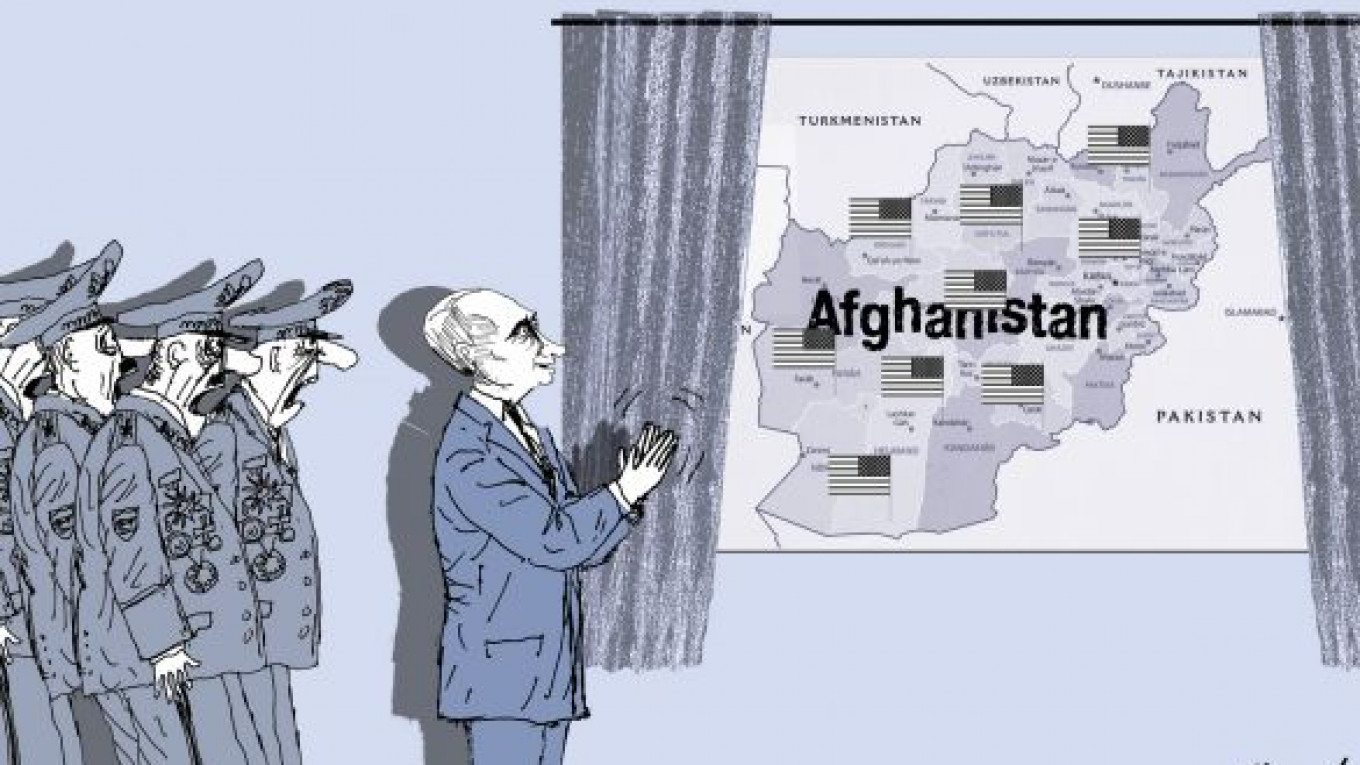

On May 9, Afghan President Hamid Karzai announced he would allow the U.S. to keep nine military bases in Afghanistan after direct U.S. participation in the Afghan war ends in 2014. How has President Vladimir Putin responded to the possibility that Afghanistan may turn into “one giant U.S. aircraft carrier,” as Kremlin-friendly political analyst Yury Krupnov ?

After Karzai’s announcement, you might have expected the Kremlin to offer its usual bluster about how the U.S. and NATO are trying to create a suffocating “Anaconda ring” around Russia — from the Baltic states, Poland, Romania, Georgia and Turkey to Afghanistan, South Korea and Japan. You might even have expected a dose of the anti-U.S. demagoguery about the U.S. government using Afghan bases to run a lucrative narcotics-export business, including daily flights of U.S. cargo aircraft filled with heroin destined for Russia and Europe. Or that U.S. bases in Afghanistan could be used for an attack on Russia. After all, Yury Krupnov and other conservative, pro-Kremlin analysts are particularly fond of reminding Russians that a U.S. nuclear missile could reach Moscow from the U.S. airbase in ?Bagram, Afghanistan, in less than 20 minutes.

Yet the Kremlin was conspicuously silent about Karzai’s recent announcement on U.S. bases. At the same time, however, this restraint was consistent with Putin’s general position on Afghan security, which he first articulated in February 2012 during a speech in Ulyanovsk, the home of a joint U.S.-Russian transit center to transport U.S. war materiel out of Afghanistan. During his speech — given to a group of elite Russian paratroopers, no less — Putin offered clear support for the U.S.-led military campaign in Afghanistan.

“We have a strong interest in our southern borders being calm,” Putin said. “We need to help them [U.S. and coalition forces]. Let them fight. … This is in Russia’s national interests.”

Putin also stressed that the U.S. accepted the responsibility of defeating the Taliban, and that U.S. forces should stay there until their mission is fulfilled.

Many didn’t recognize Putin after he pronounced these words. This is the same Putin that has never tired over the past decade of accusing the U.S. and NATO of undermining Russia’s national security by extending their military infrastructure in Europe eastward to Russia’s borders.

During the 12 years that the U.S. has led the ?Afghan war, there have been plenty of opportunities for the Kremlin to exploit U.S. failures, including the fraud-ridden Afghan presidential election in 2009 and, most recently, confirmation from Karzai that the CIA has delivered bags of cash worth tens of millions of dollars to his office since December 2001, when he became the country’s leader.

Nonetheless, there was little Kremlin-sponsored mockery of U.S. attempts to “export democracy” to Afghanistan, nor did it gloat over its favorite quibble — U.S. double standards — by pointing out that the U.S., which rarely misses an opportunity to criticize Russia’s high level of corruption, is a large source of corruption in Afghanistan.

What explains Putin’s uncharacteristic restraint regarding the U.S.-led military campaign in Afghanistan and his pragmatism concerning U.S. bases that may remain in the country after 2014?

The answer is that the security that the U.S. provides to Russia’s southern borders is so important to the Kremlin that Putin is willing, as a rare exception, to refrain from his trademark, overblown anti-U.S. rhetoric. Besides, Putin has plenty of other opportunities to play the anti-U.S card as he wishes — for example, banning U.S. child adoptions, hunting for U.S. “foreign agents” among nongovernmental organizations or blaming the opposition’s protests and the threat of an Orange-like revolution on the U.S. State Department.

There are only a few foreign-policy projects in the Kremlin’s current playbook that can help Russia extend its influence beyond its borders in a significant way. These include the proposed Eurasian Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization, or CSTO. These two important geopolitical projects can be realized, however, only if the former Soviet republics in Central Asia remain calm, peaceful and free of Islamic extremism.

But the CSTO hasn’t been able to agree on a collective military strategy to protect Central Asia from a likely Taliban infiltration after 2014. And Uzbekistan’s 2012 decision to leave the CSTO only made this task more difficult, if not impossible, to fulfill.

In the end, Putin understands that containing ?Islamic extremism in Afghanistan and Central Asia is one of the most serious national security issues facing the country. Surely, Putin hasn’t forgotten how the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan in 1996, seven years after Soviet forces withdrew from the country, and how it established close ties to Islamic extremist groups from Central Asia, such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, or IMU. In 1999 and 2000, the IMU operated out of Taliban-supported bases in northern Afghanistan to launch raids into Kyrgyzstan. The IMU was also implicated in an assassination attempt on Uzbekistan’s president in 1999.

Most important, Putin realizes that Russia has few resources on its own to prevent the Taliban and other extremist groups that are allied with it from returning to power in Afghanistan and from infiltrating Russia’s backyard in Central Asia. Putin also understands that the Americans will never be able to bring the ragtag Afghan army — which has been chronically crippled by gross incompetence, 90 percent illiteracy and a 25 percent desertion rate — up to level in which it would independently be able to prevent the Taliban from regaining Kabul.

Yet, as the U.S. prepares to withdraw by 2014, one thing is clear: Only when Putin senses a direct national security threat from Islamic extremists in Afghanistan and Central Asia is he willing to take a fair and balanced look at the U.S. If only Putin would use the same pragmatism in working with the U.S. on missile defense and a whole range of other important global issues, U.S.-Russian relations would surely reach a new level of trust and cooperation.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.