Russia's abrupt decision last week to give temporary asylum to U.S. intelligence leaker Edward Snowden caught many by surprise. After all, the Federal Migration Service had three months to decide after Snowden officially applied for asylum on July 16. Why the rush?

Had Russia waited the full three months, the gesture would have sent a modest but friendly nod to U.S. President Barack Obama. Snowden would have still been in the no-man's-land of the transit zone at Sheremetyevo Airport —? technically, not Russian territory. Sure, this would have largely been a self-?delusional game in semantics, but it would have saved Obama some political embarrassment and would have avoided a full-blown conflict with U.S. Republicans over his "soft policy" toward Russia.

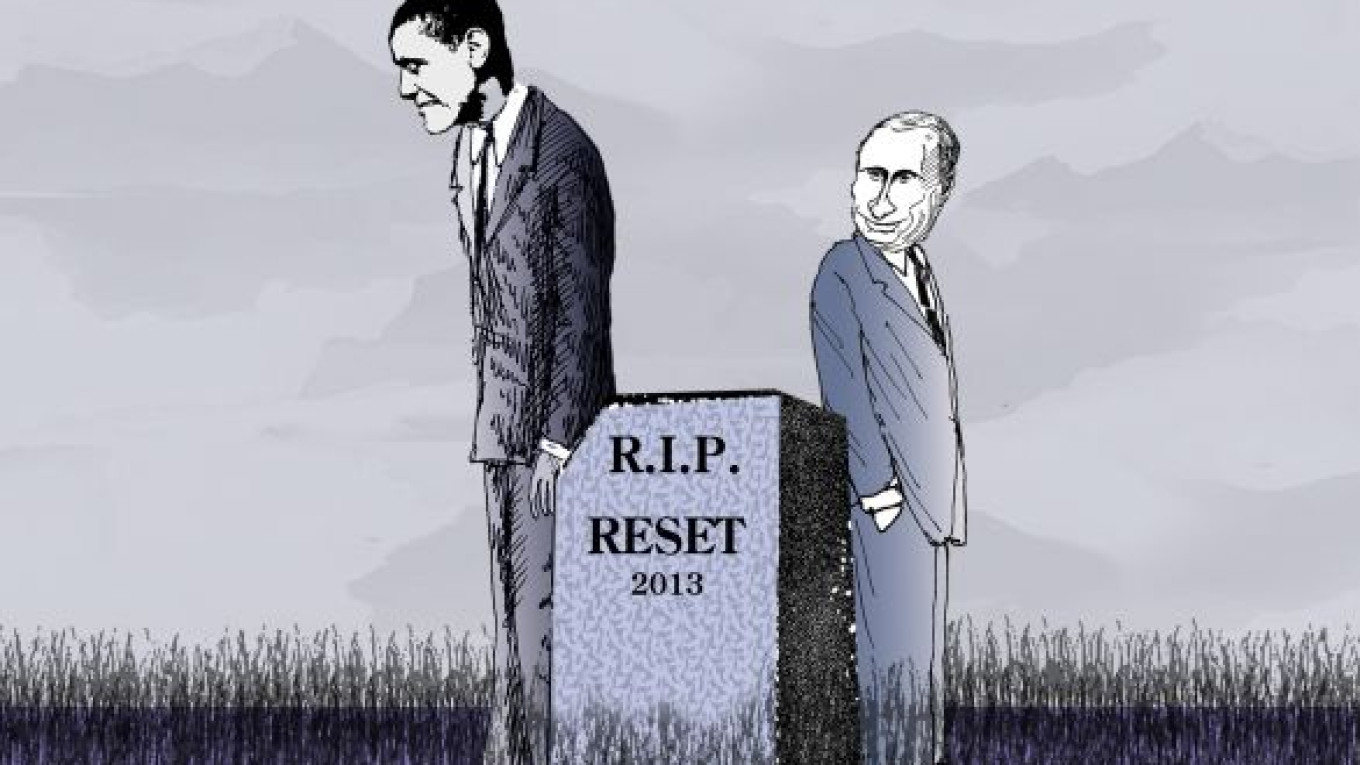

Russia's president made it easy for Obama to back out of the pair's planned Moscow meeting, writes opinion editor Michael Bohm.

Another more modest but still U.S.-friendly option for the Kremlin would have been to give Snowden documents to leave the airport but without a final decision on his asylum status. This would have at least kept Russia in neutral territory on the Snowden issue and left everyone guessing over whether Moscow would grant Snowden asylum.

But by giving Snowden temporary asylum only 2 ½ weeks after he applied, Russia seems to have gone out of its way to snub the U.S. As it turns out, Putin's now-?famous statement that Snowden could stay in Russia only if he stopped damaging U.S. interests didn't count for much in the end. Giving Snowden asylum status was, indeed, a significant blow to the U.S. At the very least, it damaged Obama's reputation, as well as U.S.-Russian relations in the short-term.

U.S. Republicans have called Russia's decision a "hostile act." Leading the pack was Senator John McCain, who said giving Snowden asylum was: "a deliberate effort to embarrass the United States. It is a slap in the face of all Americans. Now is the time to fundamentally rethink our relationship with Putin's Russia."

Even otherwise soft-spoken Democrat Senator Charles Schumer said, "Russia has stabbed us in the back, and each day that Mr. Snowden is allowed to roam free is another twist of the knife."

One explanation for Russia's hasty decision is to have made it that much easier for Obama to cancel the Moscow summit with Putin, which is exactly what Obama did on Wednesday. The White House decided that there would be little to talk about anyway during the summit — except for the old, worn-out topics of Syria, arms reductions and Iran, which the two sides do not see eye-to-eye on.

Washington is particularly tired of going around in circles with Russia on the issue of U.S. missile defense installations in Europe, which the Kremlin has always insisted must be directly linked to further nuclear arms cuts in both strategic and tactical arsenals. The perpetual deadlock on missile defense has turned into a mockery in which the U.S. continues to produce solid arguments and evidence that its missile defense cannot possibly undermine Russia's nuclear deterrent, while Russia continues to insist that it is a threat to its national security — in any configuration. Even Obama's announcement in March that the U.S. would cancel the fourth phase of its European missile defense system — the phase that most concerned Russian politicians and military brass because it could allegedly intercept strategic missiles — didn't break the ice on the issue.

Under Dmitry Medvedev's presidency, there was a clear warming of relations with Obama. In particular, the two sides signed the New START treaty in 2010, Russia supported United Nations sanctions against Iran, both sides worked closely on Russia's membership in the World Trade Organization, and Obama and Medvedev agreed on transit routes through Russia for U.S. and NATO shipments from Afghanistan.

But starting with the beginning of Putin's third presidency in May 2012, Obama took a clear "pivot" toward China and downgraded Russia to a lower priority in U.S. foreign policy.

If nothing else, the downgrade shows how low the stakes are in U.S.-Russian relations. In contrast, although U.S.-Chinese relations are much more problematic and the disputes between the two countries are more heated, both Washington and Beijing have worked hard to overcome these problems because the economic stakes between the two nations are so high.

Since the economic component in U.S.-?Russian relations is far less significant, Obama reached the conclusion that it is not worth the effort to try to revive a "reset" that has been clinically dead since December 2011, when the Kremlin started the crude propaganda campaign claiming that the U.S. State Department was trying to foment an Orange-like revolution in Russia through its support of nongovernmental organizations and the opposition movement. In addition,? USAID was kicked out of Russia because of its alleged "subversive activity," and Putin signed the law banning U.S. adoptions of Russian children.

The Kremlin's anti-U.S. campaign under Putin was proof positive of its "pivot" backward — toward the Soviet Union.

With the reset dead, there was little point in holding an ersatz summit and producing meaningless joint U.S.-Russian communiques like the last one on June 17, when the two leaders met at the Group of Eight summit in Northern Ireland. How many times can you churn out the same hackneyed phrase, "We reaffirmed our readiness to intensify bilateral cooperation based on the principles of mutual respect, equality and genuine respect for each other's interests"?

In the end, by seemingly blessing the decision to grant Snowden asylum before the planned Moscow summit, Putin all but made Obama's cancellation of the summit a given. This was Putin provocation par excellence.

It is clear that Putin doesn't care too much for Obama. The pictures of Putin's sour facial expressions at nearly every meeting with Obama speak for themselves. The tension is so high that Putin can't even offer a courtesy laugh at Obama's attempts to break the ice with jokes.

Obama may think that canceling the Moscow summit sent a strong message to Putin, particularly since Putin values these summits as a boost to his global prestige. Yet far from being a snub, Obama's no-show is probably the best news Putin has received in a long time.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.