Here's an interesting bit of news: According to information attributed to WikiLeaks and published in Britain's Guardian newspaper, Syrian President Bashar Assad wrote to his wife that he is not serious about his promised democratic reforms, has consulted with Iran about ways to put down the protests and prefers the shedding of blood to other options.

Of course, much of this was already known through previous leaks. But what is important is that, had the news been reported back in, say, mid-February, the Russian state-controlled media would have branded it as a bunch of lies.

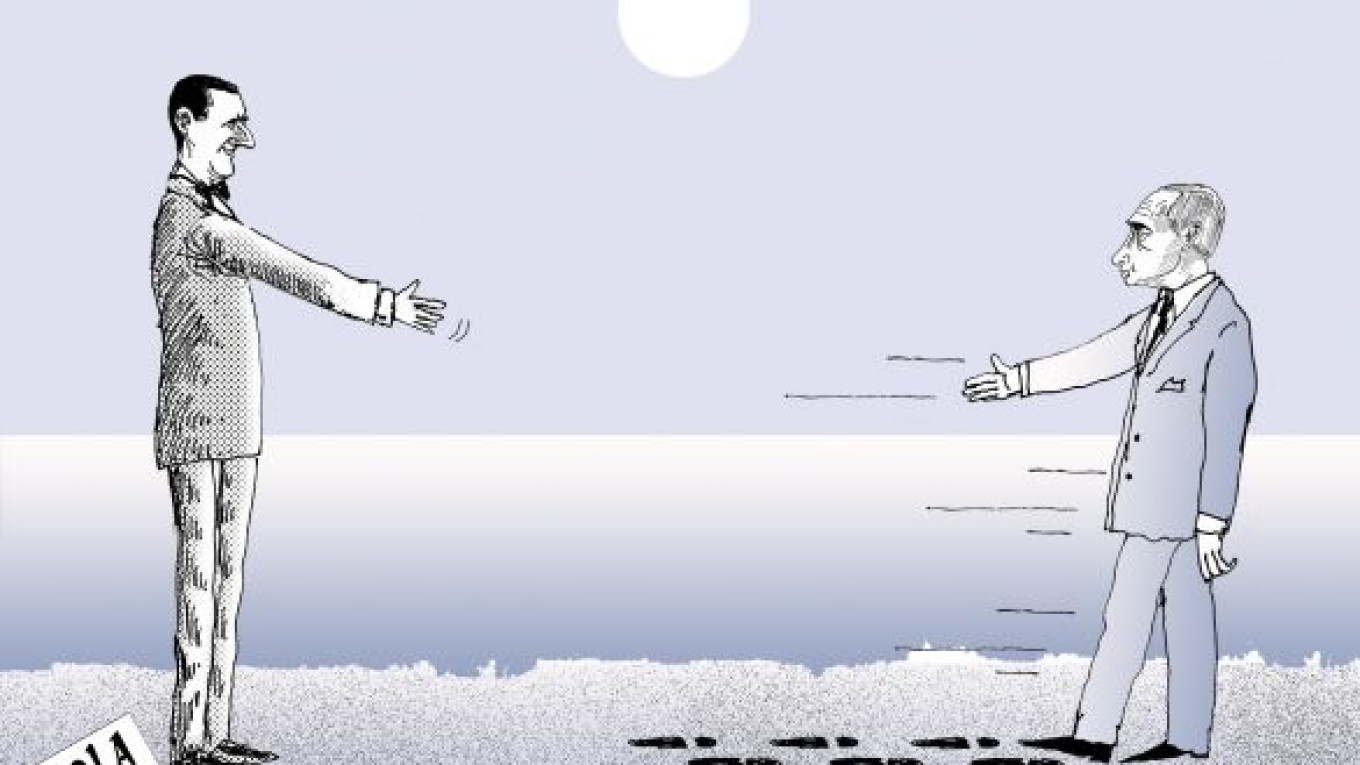

Now, after Vladimir Putin's "triumph" in the March 4 presidential election, the Foreign Ministry and media have done an about-face. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov is saying Assad "has been slow with reforms." His ministry says it is "not defending Assad at all" and is actually trying to give all Syrians equal opportunities to reform the political situation in the country.

I take some pride in saying this is exactly what I had predicted would happen. I believed that after March 4, the Foreign Ministry would suddenly "discover" so many problems with Assad that a change in Moscow's policy on Syria would inevitably follow.

Prior to Russia's presidential election, everything was just the opposite. Moscow claimed that Assad was besieged by rogue terrorists who refused to participate in the reform process that the Syrian president had proposed. In every one of his anti-Western and anti-U.S. proclamations, Putin effectively said: "We'll stand by our friend, Assad." The implication was that Moscow must first defend Assad and later Russia itself from color revolutions sponsored by foreign states like the United States. In other words, the authorities used every trick they could think of to mobilize Putin's electorate, even at the risk of isolating Russia from the Arab world.

I recently attended an IFRI conference in Paris that was ostensibly dedicated to the Arab Spring movement but that also addressed events in Russia. In the eyes of European analysts, the two "springs" are increasingly merging into a single powerful protest movement against entrenched leaders who have seized power through fraudulent elections. European analysts view events in the Arab world and in Russia as a single phenomenon stemming from similar causes — no matter how much Moscow tried to convince them otherwise at its latest Valdai Club meeting in Sochi attended by Russian and foreign political analysts. Of course, there are some differences, but they are only superficial: Russian protesters had to battle the cold in addition to the authorities and there has been no shooting on the streets of Russian cities — although the riot police turned out in greater force in Moscow than did the police in Cairo and Tunisia. However, the Russian police have employed excessive force against peaceful demonstrators, so it all evens out. For that matter, police did not fire on protesters in Bahrain, Tunisia or Egypt — where it has yet to be conclusively proven that the army brought arms to bear against demonstrators. It is also worth noting that demonstrations in the Arab world have not always led to regime change. The leadership of Bahrain remains firmly entrenched, and protests in Yemen only prompted a "castling move" in which the president switched jobs with his deputy. So the simple fact that Putin remains in power does not exclude his regime from the list of autocracies shaken by large-scale protests.

After long hours in discussions with my European colleagues, I realized that after a year of turmoil in the Arab countries, Europe is beginning to resign itself to the changes there and is establishing contacts with the new ruling elites. They are not in the least panicky about it either. They understand that moderate Islamists coming to power — as compared to seizing power — does not necessarily mean those governments will undergo a radical change in behavior. The main thing is that none of those countries plans to set up an Iranian-style Islamic republic in which the clerics hold a monopoly on power. On the contrary, they are creating and developing the mechanisms of Western-style democracy — at least for now. In fact, representatives of those moderate Islamist powers, such as the Ennahda Movement in Tunisia, took part in the conference in Europe. It is in their interest to dispel potential European fears regarding the nature of their movements' goals and methods. Thus, Europeans have adapted to and are even welcoming the changes taking place in countries affected by the Arab Spring.

It is quite another matter concerning the "Russian Spring" — or more specifically, Putin's increasingly militaristic rhetoric about the threat from Europe and the United States. This, combined with the mechanics of the recent presidential election, is even more alarming to Europeans than the Arab Spring. Europeans are seriously concerned that Putin's victory could signal the continent's return to the Cold War, a new split with Russia and a strengthening of the real threat that Russia poses to Western civilization.

Putin, Lavrov and Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin will have their work cut out for them if they want to allay those European fears. It is no coincidence that U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton took satisfaction in announcing on March 14 that the Russian and U.S. positions on Syria have moved considerably closer.

Alexander Shumilin is the director of Center for the Analysis of Middle East Conflicts with the Institute for U.S. and Canadian Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.