I have often had conversations with Russian officials who sincerely believe that the opposition movement is funded by the United States as part of a conspiracy against Russia. Belief in a sinister U.S. plot plays a central role in their entire world view.

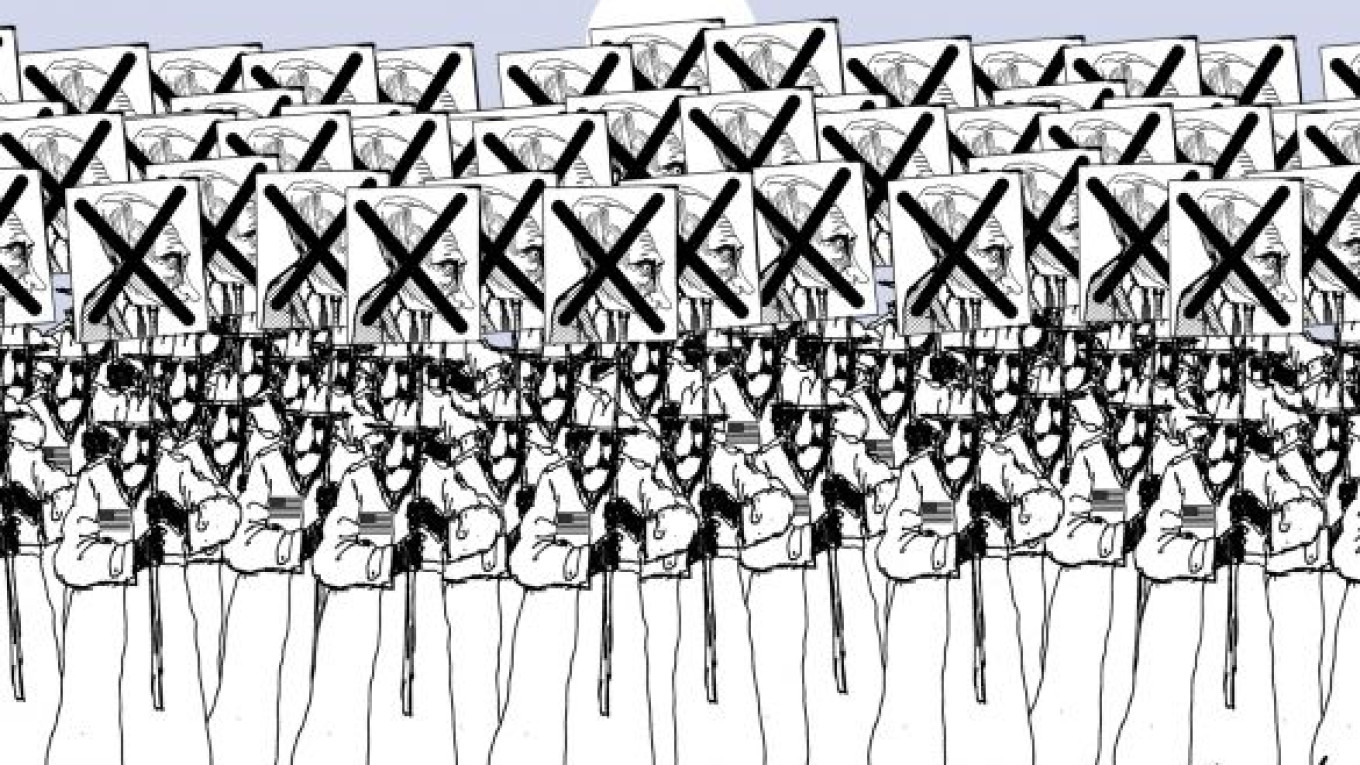

President Vladimir Putin also believes in this conspiracy. All of his past experience as a KGB agent supports the belief that nothing happens purely by chance. If demonstrators take to the streets in protest against the government, the first question Russians must ask is "Who benefits from this?" Using this distorted KGB logic, if tens of thousands of people protest election fraud and government corruption, it naturally means that foreign agents must have paid them to rally.

The authorities have long suspected nongovernmental organizations of being subversive, especially those that receive grants from abroad. For the Kremlin, it is inconceivable that a foreign sponsor would spend money on an organization in Russia out of purely philanthropic motives. There must be a hidden, political agenda, they believe. They want to "contaminate" Russian society from the inside by either imposing their hostile beliefs or by supporting "subversive elements" in Russia that challenge the Kremlin's monopoly control.

This is not the first time that government forces were mobilized to crack down on NGOs. In 2005, after overly burdensome requirements were imposed on foreign NGOs, the Kremlin had largely achieved its goal. Many NGOs were forced to close down operations in Russia because it was impossible to comply with the excessive financial and accounting requirements.

True, legislation regulating NGOs was liberalized somewhat under President Dmitry Medvedev. Financial accounting rules were simplified, it became simpler for new NGOs to register, and a number of NGOs were given tax breaks.

But now, United Russia, the sponsor of the bill, is trying to turn the clock back to 2005. The focus of the bill is to once again make life unbearable for NGOs. If it becomes law, NGOs must report every penny they receive to the authorities, and the number of inspections for NGOs receiving foreign funding will increase threefold. What's more, they will be forced to include the words "foreign agent" on all of their printed materials.

If any violations are found, NGOs will be heavily fined, and their top officials could be charged with a criminal offense.

Furthermore, those deemed to be engaged in "political activities" will be given three months to place themselves on a special list with the Justice Ministry and will be branded as "foreign agents."

The bill defines "political activity" as any attempt to "influence state policy or public opinion." By this overly broad definition, even environmental organizations could be labeled as engaging in "political activity" because they try to influence public opinion. That is the entire reason they exist.

In typical fashion, United Russia is distorting the facts by suggesting that Russia is merely following the example set by the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938. The original intent of this act was to control aggressive propaganda of foreign states amid the global rise of fascism (and, to a lesser extent, communism). Although the U.S. act remains on the books with the same name, it is now largely focused on U.S. and foreign lobbying and PR firms that represent foreign governments and high-profile individuals.

Unlike the Russian bill against foreign NGOs, the U.S. law is not concerned at all with foreign NGOs operating in the United States. It would be hard to imagine U.S. congressmen proposing a bill to hound foreign NGOs operating in the United States that focus on protecting U.S. human rights, such as defending prisoners and women against abuse, or helping the homeless, troubled teens or drug addicts in the United States.

By contrast, few Russians would even think about contributing to one of their own human rights organizations. It is not a matter of greed. Rather, it is a concern that Russian authorities — ever since Soviet times — consider such activity highly suspicious. In addition, Russian society does not yet recognize the importance of human rights advocacy to protect civil rights and liberties. As a result, most human rights NGOs operating in Russia must rely almost entirely on foreign assistance.

But things may be changing. During the protest rallies that started in December, citizens sent in private contributions to help pay for sound and stage equipment and other expenses associated with organizing a mass rally. That idea was the brainchild of leading opposition figure Alexei Navalny. Notably, the authorities have arrested dozens of people suspected of organizing "mass riots," and they are closely examining these donations to determine who gave how much and to whom. Donors may soon face legal troubles from the authorities.

If the Kremlin thinks that it can stigmatize NGOs by arbitrarily labeling them "foreign agents," it is dead wrong. During Soviet times, the people turned to Voice of America and Radio Liberty broadcasts to get truthful information. They were the only alternative to the blatantly false Soviet propaganda.

Just like during the Soviet period, Russians are sick and tired of government lies. If NGOs help to disseminate the truth about election fraud, corruption and other abuses, Russians will always have more faith and trust in these "foreign agents" than they will in the government.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.