Not long ago, the government had based its revenue and spending plans on an average oil price of $75. At that level, the budget deficit was supposed to be near zero. Things have changed dramatically since then, and now an oil price of about $110 is needed to balance the budget. In the six years between 2004 and 2011, average annual government spending has increased at a rate of 25 percent on the back of unexpectedly high oil price-related revenues.

Since average inflation, using the gross domestic product deflator, was "only" about 13.3 percent in that period, with real GDP growth in the order of 4.5 percent, the share of government spending, including social benefits, has increased significantly to about 38 percent. Compared to Western countries such as France or Sweden, the ratio is still quite low and is not worrisome. But it is the lopsided and volatile nature of revenues that poses a serious problem. It makes long-term economic planning difficult, both on the micro and macro level. A good tax system must aim to raise funds from the whole population. It should have a good mix of direct and indirect taxes and contributions, guided by the ability-to-pay principle where the rich pay proportionally more than the poor.

As it is, the government — and the country — has thus become more dependent on oil in recent years. Should the oil price decline a lot — as in 2008 when it fell from $145 to $35 — the government budget deficit could reach 10 percent or more of GDP. A large ruble depreciation and a deep recession would be just two of a whole series of negative effects from large budget deficits.

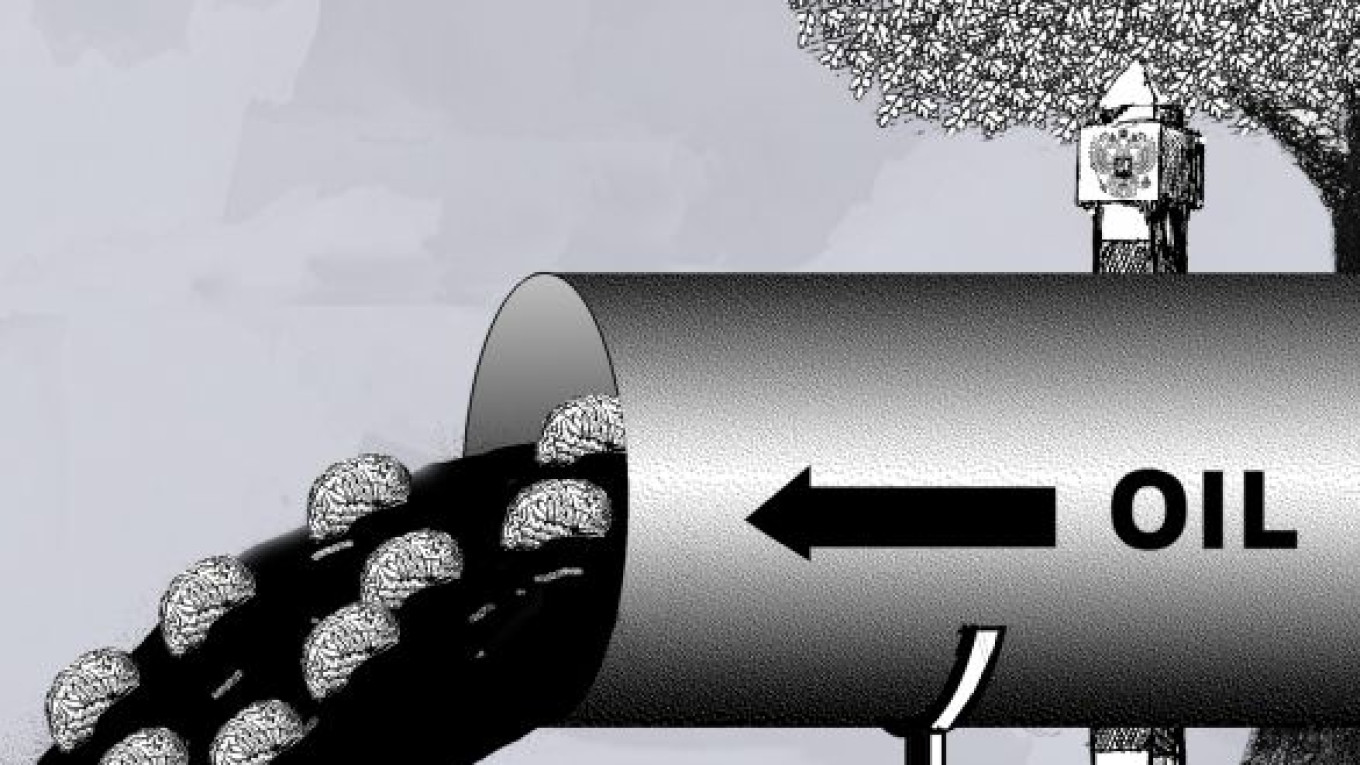

This, however, is not very likely, but the possibility should be kept in mind and should spur policymakers to broaden the production base of the economy. Marek Belka, head of Poland's central bank, raised an interesting point at the Gaidar economic conference in Moscow last week. He said a country that is overly dependent on commodity exports will suffer a so-called brain drain. Skilled people leave the country in large numbers because capital-intensive commodity production crowds out jobs in other sectors. Now that shale gas production has gathered momentum, Belka is afraid that Poland will become like Russia. Poland could acquire an overvalued exchange rate caused by commodity-driven trade surpluses, which in turn will make manufactured imports cheap and destroy domestic production in other sectors. Once again, the Dutch disease.

As for where oil prices will be in 2012, fundamental factors clearly do not argue for a decline of oil demand. This year will not be a repeat of 2008 and 2009. The outlook is much better. In 2012, global GDP will probably expand 2 percent in real terms, which is 1.5 percentage points below pre-crisis trends. Oil demand will keep falling in the United States, in Western Europe and Japan, most likely exceeding China's expected increase in oil demand to 6 million barrels per day this year. To put this in perspective, global demand is presently 89 million bpd. At the same time, however, new oil fields in Brazil, Canada, Angola and the Gulf of Mexico are now coming on stream and Libya's and Iraq's oil production is back to normal. Surplus capacity is presently about 4 million bpd.

In addition, oil market disruption caused by potential military action in the Middle East is already priced, while the likelihood that Iran would instigate a military conflict is low. Provoking an attack from Israel or the United States by closing the Strait of Hormuz would deprive itself of its lifeblood.

On balance, though, oil prices are on the way down. Brent could fall from $110 today to $90 at year-end. For Russia, even such a reduced price level is very attractive. The balance of trade surplus would shrink but remain one of the world's largest. In such an environment, Russia's real GDP will probably exceed last year's level by 3 percent to 4 percent. The extraordinary soundness of government finances can comfortably accommodate an increase in the government budget deficit from close to zero percent of GDP in 2011 to perhaps something like 3 percent this year. Such an increase will not lead to a significant ruble depreciation. More important, a rising fiscal deficit is an appropriate anti-cyclical, demand-stabilizing fiscal policy. The government will partly fill this gap that will be created by the likely decline of net exports.

For investors, a reallocation of Russian equity portfolios from oil, gas and metals toward stocks that benefit from solid domestic demand is the best strategy at this point. Sberbank has suddenly become a very good alternative to troubled Western banks. Since real disposable incomes will continue to rise quickly, retail and consumer goods stocks are plausible bets as well. The Russian stock market remains the world's cheapest. The average price-to-earnings ratio of 5.4 compares with Canada's 15.1, Australia's 13.6, or South Africa's 12.1, the world's other important commodity countries. Foreign and domestic investors obviously take risks very seriously, but they may actually be lower than market participants assume at this point.

Dieter Wermuth is a partner at Wermuth Asset Management.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.